This article provides a high-level overview of approaches to ESG disclosures in the United States, European Union, and United Kingdom, noting the implications of these differences for investors and global businesses. Beyond shedding more light on the general ESG regulatory landscape under these regimes, the article explores the emerging ESG regulatory frameworks and policy drivers for ESG on both sides of the Atlantic and delves further into the implications of these differences to investors and multinational corporations, and why companies should care about these regulatory requirements and differences.

What Is ESG and ESG Disclosure?

ESG, which stands for “environmental, social, and governance,” refers to metrics often used by analysts to evaluate and vet the non-financial sustainability impact and social consciousness of companies. These metrics can impact a company’s risk profile and public perception—and, ultimately, the bottom line.

“ESG disclosures” are specific metrics used by organizations to report on their ESG performance and initiatives. ESG disclosures are generally broken into three categories:

- Environmental: focuses on climate risks, emissions, energy efficiency, use of natural resources, pollution, and biodiversity

- Social: focuses on human capital; labor regulations; diversity, equity, and inclusion (“ DEI”); safety; human rights; and community engagement

- Governance: focuses on board diversity, corruption and bribery, corporate ethics and compliance, compensation policies, and risk tolerance

The terms ESG disclosure, sustainability report, and corporate social responsibility report are often used interchangeably.

Overview of the ESG Disclosure Regimes in the US

Federal Government

ESG disclosure in the United States (“US”) remains largely voluntary, except for the state of California’s requirements, discussed below. Governmental agencies and shareholder activists, however, continue to advocate for mandatory ESG disclosure. On March 6, 2024, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) adopted climate-related disclosure rules, two years after publishing the proposed rules.[1] Shortly thereafter, on April 4, 2024, the SEC stayed its climate disclosure rules following a flurry of lawsuits by many stakeholders challenging both the rules and the SEC’s authority to issue the rules.[2] A total of forty-three states (twenty-five against and eighteen advocating for the SEC rules as intervenors), as well as interest groups and trade associations, have since filed their petitions for review across different appellate courts, which are now consolidated in a multidistrict litigation in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit, dubbed Iowa v. Securities & Exchange Commission.[3] Many opponents to the SEC’s ESG disclosure rules argue that following the Loper Bright decision[4] by the US Supreme Court, which overturned the long-standing Chevron deference doctrine,[5] the SEC lacks authority under federal securities laws to require corporate reporting of greenhouse gas emissions and other climate disclosures. This case remains in litigation and the rules are stayed. In any event, many experts believe that the Trump administration will abandon the rules.[6]

State of California

In 2023, the state of California enacted Senate Bill 253 (“SB 253”) (“Climate Corporate Data Accountability Act”) and Senate Bill 261 (“SB 261”) (“Greenhouse Gases: Climate‐Related Financial Risk”) as part of the Climate Accountability Package. These laws are applicable to both public and private US companies “doing business” in California.[7]

Senate Bill 219 (“SB 219”) was proposed and signed into law on September 27, 2024, amending the Climate Accountability Package by granting the California Air Resources Board (“CARB”) time and discretion to adopt implementing regulations and clarify answers to key implementation questions. While SB 219 extended CARB’s implementation date from January 1, 2025, to July 1, 2025, it does not offer an extension of the date of first reportable data under SB 253 for Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, which remains January 1, 2025.[8] This means that US entities required to report under SB 253 may still have to collect Scopes 1 and 2 data for the first half of 2025 and include this in their first report to CARB, due by January 1, 2026.

On December 5, 2024, CARB issued an enforcement notice indicating its intent to exercise “discretion” in enforcing SB 253 during the first 2026 reporting cycle to allow companies additional time to implement data collection necessary to comply with the reporting requirements.

Shortly thereafter, on December 16, 2024, CARB issued a feedback solicitation inviting public comments on the implementation of SB 253 and SB 261, due by February 14, 2025.

Overview of the ESG Disclosure Regimes in the EU and the UK

Prior to 2023, only a relatively small number of large companies (referred to as public-interest entities)[9] within the European Union (“EU”) were required to disclose ESG information under the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (“NFRD”), which came into force in December 2014. Work to substantially expand the scope of the NFRD started in 2017 on the heels of the 2016 COP21 Paris Agreement.[10] In January 2023, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (“CSRD”) came into force.[11] However, please note our commentary below in relation to changes being proposed to the CSRD.

The CSRD is a mandatory ESG disclosure framework that modernizes and strengthens ESG reporting, requiring companies to report on environmental and social impacts, risks, and opportunities. EU member states were required to transpose the CSRD into domestic legislation by July 6, 2024; however, some countries have not yet done so (e.g., Germany, the Netherlands, and Spain).

The CSRD is broad and reaches a much wider group of companies compared to the NFRD, including some listed small and medium-sized enterprises (“SMEs”); certain non-EU issuers; and non-EU parent companies that generate over EUR 150 million in the EU and have at least one large subsidiary, public interest SME (see definition of public-interest entities in note 9), or branch in the EU. It requires businesses to report and disclose information on their societal and environmental impact and external sustainability factors affecting their operations.

A key feature of the CSRD is the double materiality assessment (“DMA”). The materiality of risks is reportable on two fronts: (1) how sustainability issues may affect the company and (2) how the company may impact people and the environment. The concept of DMA is yet to be established, with no proven or approved methodologies. This is causing some confusion in the marketplace and has been a source of criticism.

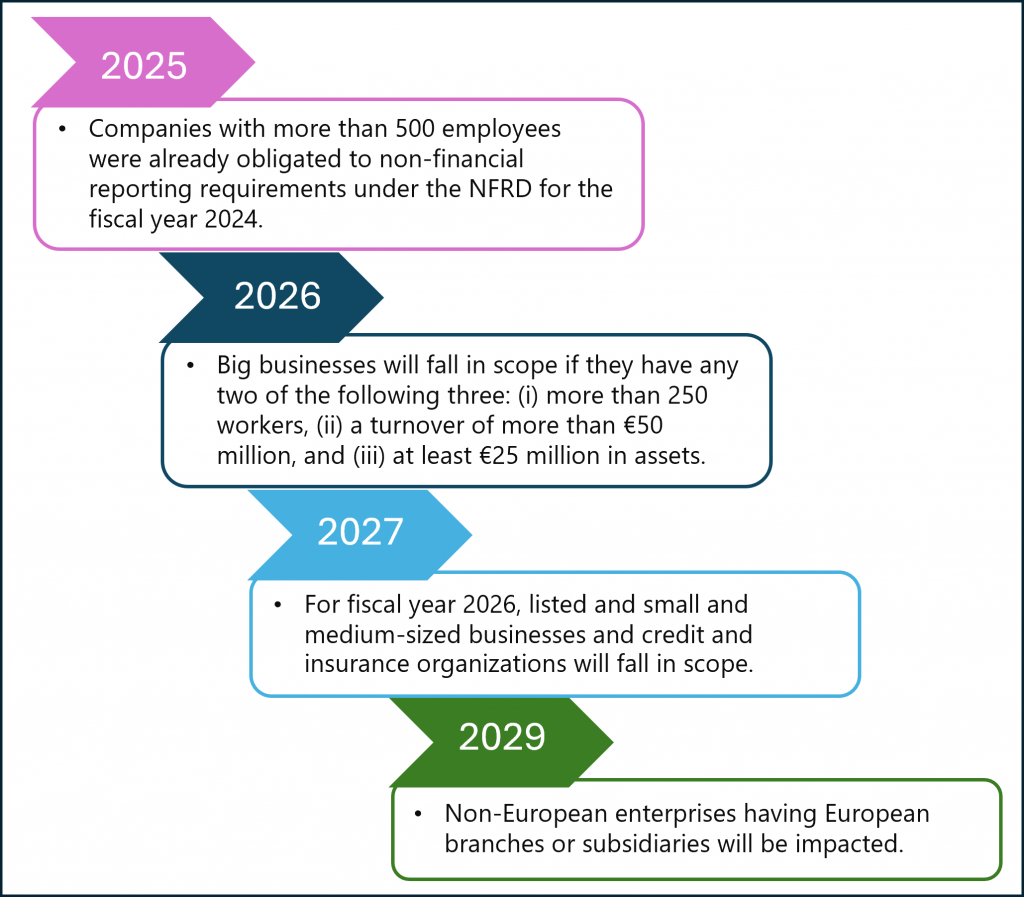

Implementation of the CSRD is a phased-in approach, with a rolling timeline (see figure 1). Companies already reporting under NFRD and large issuers with more than 500 employees are required to submit their ESG disclosures under CSRD in 2025, covering FY 2024. Other “large” EU companies or corporate groups (which includes those with two of the following three: (a) EUR 50 million+ in net turnover, (b) EUR 25 million+ in assets, and (c) 250+ employees) are required to submit initial ESG disclosures in 2026, covering FY 2025. Finally, all non-EU ultimate parent companies with “large” EU subsidiaries or operative branches are required to submit their initial ESG disclosures in 2029, covering FY 2028.

Figure 1. Timeline of Implementation of the CSRD.

Upstream of reporting, certain companies (including non-EU businesses) will be required to comply with the EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (“CSDDD”). This regulatory framework provides a process for mapping and conducting an in-depth assessment of a company’s operations and its chain of activities in order to (i) identify and prioritize actual and potential impacts based on the severity and likelihood of occurrence, (ii) prevent potential adverse impacts through an action plan with “reasonable and clearly defined” timelines, and (iii) end any actual adverse impacts by minimizing the impact with corrective action plans.[12] The CSDDD has regulatory enforcement requirements and civil liability for violations.

It is important to note that on February 26, 2025, the European Commission published an “Omnibus package” (“Omnibus”)[13] that seeks to simplify and streamline the requirements under the CSRD, the CSDDD, and the EU Taxonomy Regulation.

Some of the key proposed changes to CSRD include introducing a two-year delay to the reporting requirements applicable to “large” EU companies (from FY 2025 to FY 2027, with the first reports due in 2028 rather than 2026) and amending the thresholds applicable to in-scope EU companies (the reporting requirements would only apply to entities with more than one thousand employees either at the individual or group level and with either (a) EUR 50 million or more in net turnover or (b) EUR 25 million or more in assets). The Omnibus also proposes changes to the thresholds applicable to non-EU ultimate parent companies with “large” EU subsidiaries or operative branches.

The Omnibus also includes changes to the CSDDD, which affect scope and timeline of reporting, as well as potential removal of the requirement for EU member states to introduce civil liability for violations.

It is still unclear whether the changes proposed by the Omnibus will be adopted and what the timing of that would be, although the European Commission has invited EU institutions to treat this matter as a priority in light of the upcoming compliance deadlines under the CSRD.

In the United Kingdom (“UK”), there are also mandatory ESG reporting requirements that apply to certain in-scope companies. Since 2019, listed companies and large companies have been required to disclose energy use and carbon emissions under the Energy and Carbon Report Regulations 2018[14] (“Streamlined Energy and Carbon Reporting” (“SECR”)). Listed companies are required to make disclosures aligned with the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures framework. For accounting periods starting from April 2022, the Companies Act 2006 has required UK high-turnover companies with more than 500 employees, as well as traded insurance and banking companies, to produce a non-financial and sustainability information statement as part of their strategic report.

Looking ahead, the UK government is considering whether to introduce new sustainability disclosure requirements (“SDR”) on companies under a new reporting regime based on the standards issued by the International Sustainability Standards Board (“ISSB”), as well as a requirement for certain entities to publish climate transition plans. As these new regimes are still being developed, UK and non-UK entities will need to consider the extent to which any changes will affect their reporting obligations. Alongside the new disclosure requirements, the UK is also developing its own UK Taxonomy Framework for determining which activities can be considered “environmentally sustainable.”

Table 1, below, compares the main reporting frameworks in the EU and the UK.

Table 1. Main Reporting Frameworks in the EU and UK

EU | UK |

Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (“SFDR”)[15] | Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (“TCFD”) (mandatory) |

EU Taxonomy Regulation | UK Taxonomy Framework (to be confirmed) |

Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (“CSRD”) | Streamlined Energy and Carbon Reporting (“SECR”) regulations |

Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Disclosure Directive (“CSDDD”) | Sustainability Disclosure Requirements (“SDR”) and standards aligned with the International Sustainability Standards Board (“ISSB”) (to be confirmed) |

Comparing the Disclosure Regimes in the US and the EU/UK

While the topics addressed by ESG regulations vary across regimes, they all include a focus on greenhouse gas emissions and other climate-related matters. It is important to recognize that reporting beyond climate topics—such as biodiversity, pollution, and certain workforce metrics—is also typically required. The reporting frameworks require a description of how risks are identified and managed, as well as corporate board oversight of identified risks. The identification of the applicable risks is fundamental and is an area where it is particularly essential to create a cross-functional approach.[16]

The most significant differentiators between the US and EU/UK disclosure approaches are the “scope and scale” of disclosures and the definition of materiality.

First, with respect to scope and scale, the CSRD covers a broad range of topics and applies to a wide group of entities, including large companies, non-EU parents of large EU subsidiaries, and certain listed SMEs operating in the EU (although this may be subject to change if the Omnibus is adopted). On the other hand, the SEC’s disclosure rules focus specifically on climate-related information, particularly climate-related risks and Scope 1 and 2 emissions, and are applicable to both registered US domestic issuers and foreign issuers. Note, however, that California’s ESG reporting requirements also include Scope 3 emissions disclosure.

Second, the meaning of materiality in each regime is critical since it determines reportability. An incorrect interpretation or an invalid assessment of materiality could be very expensive and detrimental, triggering hefty fines and sanctions. The CSRD applies a double materiality approach, which requires companies to report on how sustainability issues affect their business and how their business impacts society and the environment. The SEC rules focus solely on financial materiality, requiring companies to disclose information that is material to investors. California’s laws require extensive emissions reporting irrespective of materiality.[17]

Conclusion: The Transatlantic Divide and Why Global Companies Should Care

While ESG disclosures in the EU are mandatory, reporting in the US remains voluntary, with the exception of California’s requirements. As such, compliance with evolving ESG disclosure requirements will become more complex for global public companies. In particular, private equity funds and traditional energy players that have an increased interest in energy transition to meet stakeholder demands and regulatory changes will continue to wrestle with varying ESG reporting requirements. These critical interests are coupled with the challenges of addressing escalating climate change risks and supplying the world’s insatiable energy demand. The combination of these factors in a fast-paced business arena presents a ripe environment for ESG-related claims.[18] With more disclosure requirements and a lack of standardization across global jurisdictions, it is likely that there will be more missteps. Noncompliance with the reporting requirements in the applicable jurisdiction(s) may be fatal to potential ventures, investment opportunities, and the public perception of involved parties.

Companies, advisers, funds, and counsel should carefully curate their reviews, vetting, and setting of ESG targets to ensure alignment with required ESG and sustainability reportable information across regimes, while at the same time ensuring alignment with other investment materials, offering documents, and annual reports. In addition, disclosures should be vetted by external experts and legal counsel to ensure consistent, reliable, and accurate reporting.

See Press Release, U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n, SEC Adopts Rules to Enhance and Standardize Climate-Related Disclosures for Investors (Mar. 6, 2024). The SEC disclosure rules—aimed at reducing greenwashing, increasing transparency for investors, and standardizing and harmonizing reporting metrics across all industries—were intended to be effective beginning with the year ending December 31, 2025, and would require disclosure by public companies to include governance issues, risk management strategies, and financial implications of climate-related risks. ↑

See U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n Order Issuing Stay, In re Enhancement and Standardization of Climate-Related Disclosures for Investors, File No. S7-10-22 (Apr. 4, 2024). The SEC disclosure rules were stayed in April 2024 following challenges by several states, investors, interest groups, and trade associations. ↑

No. 24-1522 (8th Cir. 2024). ↑

Loper Bright Enters. v. Raimondo, 144 S. Ct. 2244 (2024) (providing that courts should use their own judgment when interpreting ambiguity in laws and not rely on agency interpretations). ↑

Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Nat. Res. Def. Council, 467 U.S. 837 (1984) (providing that courts were to give deference to agencies where there was ambiguity in the law, as long as the interpretation was reasonable). This case has since been overturned. ↑

Tim Quinson, Trump Administration Seen as Likely to Dismantle ESG Rules, Bloomberg (Nov. 7, 2024). ↑

See S. 253, 2023 Leg., Reg. Sess. § 1(l) (Cal. 2023); S. 261, 2023 Leg., Reg. Sess. § 1(j) (Cal. 2023). Signed into law in 2023, SB 253 and SB 261 establish greenhouse gas emissions and climate-related financial risk reporting requirements for corporations that meet certain criteria. SB 253 (greenhouse gas emissions disclosure) tasks the California Air Resources Board (“CARB”) with promulgating regulations requiring US-based entities with $1 billion or more in annual revenue to report their greenhouse gas Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions for 2025 by January 1, 2026, and Scope 3 emissions starting in 2027 for emissions for 2026. SB 261 (climate-related risks reporting) applies to companies with total annual revenues over $500 million and mandates disclosure of climate-related financial risks and measures for risk reduction. ↑

See S. 219, 2024 Leg., Reg. Sess. § 1(c) (Cal. 2024). SB 219 gives CARB six additional months to finalize its rules under SB 253, pushing the CARB implementation deadline to July 1, 2025. Additionally, SB 219 eliminates the filing fee requirement for corporations reporting their greenhouse gas emissions, gives CARB the option (but not the requirement) to contract with an outside organization to develop a program by which the required disclosures would be made public, and authorize any corporate disclosures to be consolidated at the parent company level. ↑

These are defined as EU entities with transferable securities admitted to trading on an EU-regulated market, certain credit institutions, insurance undertakings, or other entities designated as such by EU member states. ↑

The Paris Agreement is a legally binding international treaty on climate change. It was adopted by 196 parties at the UN Climate Change Conference (COP21) in Paris on December 12, 2015, and entered into force on November 4, 2016. ↑

Directive (EU) 2022/2464 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 Amending Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Directive 2013/34/EU, as Regards Corporate Sustainability Reporting, 2022 O.J. (L 322) 15. ↑

Directive (EU) 2024/1760 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence and Amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937 and Regulation (EU) 2023/2859, arts. 10–11. ↑

Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council Amending Directives 2006/43/EC, 2013/34/EU, (EU) 2022/2464 and (EU) 2024/1760 as Regards Certain Corporate Sustainability Reporting and Due Diligence Requirements, COM (2025) 81 final (Feb. 26, 2025). ↑

The Companies (Directors’ Report) and Limited Liability Partnerships (Energy and Carbon Report) Regulations 2018, SI 2018/1115. ↑

Note that the SFDR only applies to certain asset managers and other financial market participants rather than corporate entities more generally. ↑

See Europe’s CSRD Is One of the Latest Global Disclosure Regulations Revolutionizing ESG Reporting, PwC (last visited Mar. 1, 2025). ↑

Ery Dimitrantzou, How California Rules Shape Global ESG Reporting, Cority (Nov. 15, 2024). ↑

Saijel Kishan, ESG Litigation over Social Issues Is Poised to Rise, Bloomberg (Feb. 23, 2022). ↑