Blockchains reduce the need for “trust” in legal transactions. From a legal perspective, trust has some specific meanings with respect to custody, control, and transactional risk. It can be accurately defined as “reliance on assurance of others to reduce transactional risk.” Blockchains radically shift the economics of providing transactional assurances.

For example, blockchains reduce the cost and complexity of obtaining assurances of asset ownership and control. Blockchain offers a cheaper and more reliable mechanism of creating, storing, and proving evidence.

Commercial and financial legal processes currently rely on numerous systems to reduce overall transactional risk and give people enough confidence to transact. A critical legal inquiry regarding any kind of property is, who owned title, when, and what is the transactional history? In asset transactions, property registries provide custodial and financial histories. To risk buying an item or making a loan secured by property, a buyer or creditor must be able to verify that the person purporting to own the property really does have title, and that there are no other enforceable inconsistent claims.

For high-value, complex transactions, this means obtaining assurances of (1) proof of authoritative title to an asset (title is clean and untampered), and (2) proof that the proof of title is reliable (the source of assurance (1) is clean and untampered). Underpinning it all is property law. Rules of property law apply whether the object in question is a house, a retail installment contract, or a digital token. Critical to property law is the concept of title, or ownership of property.

Legal systems have developed multiple property registries and custodial systems to manage information and give buyers, lenders, and invested parties the ability to verify whether a specific deal represents an enforceable obligation. Financial market infrastructure spends tremendous sums to maintain structures that provide assurances of things like chain of custody and title.

Registries. Creditors and other interested parties file notices with deeds registries, secretaries of state, departments of motor vehicles, and places a creditor checks for notice of an adverse interest. Common examples are land registries and, in the United States, the U.C.C.-1 filing registry within a state. The registry record is deemed authoritative for legal enforcement of contracts, and insurers, lenders, buyers, and sellers rely on it equally to track rights and obligations. The records produced by central property registries supply chain of title and custody details.

Registries like these developed out of need: without a reliable system for registering, or “perfecting,” one’s interest in property, market confidence in buying, selling, and lending is disincentivized. Functional registries make functional markets.

Custody and Control of Intangibles. Second-and-third order monetization of a value stream often involves intangible property. For example, financial products leverage contract rights and obligations to create additional assets and revenue streams like securities and derivatives. In pre-internet commerce, custody and control of intangible assets were proved by “possession”; a lender holding a note as a security pledge against a loan might actually take possession of the note. It is impractical to run valuable paper instruments from holder to holder in real time, so the notes were placed with a trusted third party who acted as intermediary, for example, holding the notes in custodial trust, matching and settling promises to pay. The market assigned possessory rights to custodial agents who held assets “in trust” and maintained their chain of title so deals were free to flow without paper slowing them down.

Electronic Contracts. With the advent of electronic contracts, the law evolved a new method of perfecting a security interest in digital originals of notes and chattel paper. The key, when vaulting an electronic contract, is to prevent multiple copies that might result in adverse claims, or “double spends” of the same obligation. Sounds familiar!

Electronic contracting laws like Uniform Electronic Transactions Act (UETA) established standards for vaulting and proving custody and control of digital assets. The UETA drafters, however, noted that their recommendations were based on late-20th-century technological capabilities to establish “control.” UETA’s custodial “control” requirements substitute for possession to perfect electronic contracts in the absence of a unique digital “token” to represent a contract. The drafters looked to the market to develop better systems of digital asset control.

Where Blockchain Comes In

A better property registry. Blockchain gives us a decentralized, tamper-evident record of what happened and when with respect to data stored in specific tokens. This tamper-evident ledger means less reliance on central authorities to prove the integrity of assets. A blockchain-based property registry proves its own transactional history.

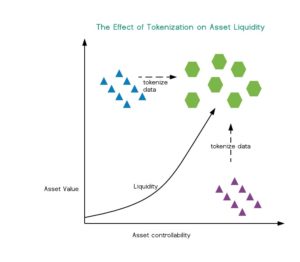

Assets that prove their own chain of custody. Blockchain-based data objects can represent any number of property types extrinsic to the blockchain, as well as assets that are native to digital technology, e.g., tokens. A blockchain-native asset represented by a token is inherently and immutably tied to its transaction history. This means assets stored in a blockchain can prove their own titles, chains of custody, and transactional records.

Blockchains can get chain of custody right. Without structures that prove chain of custody, the lack of reliable proof structures has a chilling effect on legitimate commerce. Blockchain offers a low-cost way to scale legal infrastructure and build commercial rails on the bedrock of rule of law.

Poorly controlled legal proof structures are also a problem with existing custodial systems. For example, after the 2008 recession, we learned of multiple frauds in the system of keeping chain of custody of loan records. Many assets were so poorly tracked that when it came time to enforce legal rights, creditors were left holding assets with chains of custody any lawyer could challenge to defeat the creditor’s claim. Blockchain storage of contract assets solves this problem, ab initio.

Blockchain proof of title, custody, and transaction history reduces the need to rely on external assurances. This opens economic potential wherever there was previously a lack of reliable legal infrastructure. Along the way, blockchain will shed light upon, and drive the transition to, more efficient methods of proof in digital infrastructure.

Nina Kilbride