Introduction

Reading poetry, or any fictional text, is a mental dialogue between author and reader. Each of us is free to bring our own life experience and emotional reaction to how we interpret the text. The precise words, the author’s intent, and whether those words exist within the poem or commentary around it matter less than our reactions. Reading the law of the modern regulatory state is fundamentally different. It is not like reading fiction, or even the news, because the legal framework of the regulatory state is about the power of the government over the governed. The legal texts set the limits of the power of those who govern us. The words of the legal framework create the tools by which the three branches of government exercise that power. So, the words matter, the intent matters, and where in the hierarchy of power—and by whom—the words have been written matter. Given that it is about the power of the state, legal reading is constrained by its own norms and principles. It is not ordinary reading.

In today’s world, trained lawyers are not the only readers and interpreters of the legal framework and its legal texts.[1] There are many others with specialized knowledge or expertise who I call “regulatory readers.” The supervisors at the banking agencies are among the most important regulatory readers. In the private sector, one finds them in risk management, compliance, finance, and in policy positions in government and regulatory affairs. For many regulatory readers, interpreting the legal framework is core to their job responsibilities, and in our republic, there have always been citizen readers of the law. All this is as it should be. Yet in the post-New Deal construct, the full nature of the legal framework through which the regulatory state exercises its power has not been made as clear as needed.

It is, in my view, not taught well enough in most law schools with their continued overemphasis on case law. I realize that many top law schools have moved to remedy this problem with first-year courses that teach the post-New Deal administrative state. Years of teaching financial regulation as an adjunct at both Columbia and Harvard as well as training young lawyers at Davis Polk have led me to the view that even the brightest law students have not been given the proper grounding in how the regulatory state really works. The training of regulatory readers is a catch-as-catch-can, haphazard mess in urgent need of improvement.[2] It is fair to question how much training on the legal framework of the regulatory state the resource-constrained banking agencies have been able to give their supervisory staff.[3] Just a comparison of the number of lawyers to the number of examination staff at each of the agencies tells us that deep training on the law, legal interpretation, and the legal framework has not been possible.[4] And yet, since the early 2000s, which ushered in a new era of anti-money laundering compliance, and as accelerated after the financial crisis with its increased emphasis on governance, legal risk, and compliance, supervision has become much more legally infused. In the private sector, some compliance officers initially train as lawyers but may or may not have had training in the regulatory state. Many in compliance and risk officers have had no training at all in the legal framework.

This article aims to demystify the legal framework and legal interpretation for the newly minted, digital-native lawyer and for the curious regulatory reader, using the banking sector as a case study. It begins with a discussion of the legal framework and its hierarchy as it actually exists in the banking sector—not as it may have been taught theoretically in law school for young lawyers or ignored in compliance with law training for regulatory readers. It moves on to a discussion of the traps that await the unwary who rely solely on the banking agency websites for their sources of legal texts. It then seeks to explain why reading legal texts is not as unconstrained as reading poetry and other nonlegal texts. Finally, the article concludes by observing that a deeper understanding of these points is critical as we stand on the cusp of moving from the age of internet searching to the age of augmented machine reasoning in legal interpretation.

The Legal Framework and Its Hierarchy

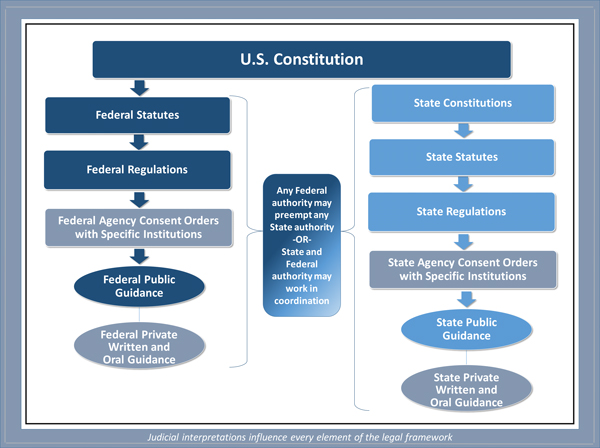

At the top of the hierarchy is the U.S. Constitution, followed by federal statutes and regulations, as well as applicable state statutes and regulations, agency consent orders, public written guidance, and private written and oral guidance, which may or may not be preempted and which interact with federal law and regulations in complex ways. Each banking organization will have its own policies, some of which go beyond the legal framework. Judicial case law and canons of statutory and regulatory interpretation also must be considered. The graphic below sets out the structure. Although this explanation may be basic to more experienced regulatory lawyers, it is not widely understood by many regulatory readers, and as Chief Justice Strine of the Delaware Supreme Court has noted, not even to some of the younger digital-native lawyers.[6]

One key difference in how this article and the graphic below explain the legal framework and its hierarchy is that they take into account both the formal legal structure (constitutions, statutes, regulations, and case law) and the supervisory structure (agency examinations and guidance, only part of which is public). Law schools classically teach only formal regulation but not supervision.[7] By sharp contrast, the training of examiners, risk professionals, and compliance professionals is overweighted in supervision and guidance and underweighted in statutes, regulations, and case law.

The Legal Framework

When interpreting a legal text, it is critical to know where it sits in the hierarchy. If there is an inconsistency among principles or text, the text higher in the hierarchy wins. The U.S. Constitution trumps a statute, which trumps a regulation, which trumps guidance. The interaction between federal and state law is more complex, especially in the banking context. Of course, the U.S. Constitution always trumps a state law. The interaction of federal and state law, however, will depend upon whether the federal government has decided to preempt or coordinate with state law. In the banking sector, it is every which way.

What happens more often is that the lower-level text must be read in light of the higher-level text. It is a common error in the internet search era to rely on the most detailed text that appears to most precisely answer the question without looking to see where it fits in the hierarchy. No text is an island and should not be read as such. Part of the reason for this misunderstanding is the blessing and curse of our ability to Google up answers. We may think that our search has found the right result because detailed and precise text appears on our screen, but unless we position it within its proper place in the legal framework and check that it is still valid, it is easy to become confused. Digital searching can also sometimes lead to confusion between proposed and final texts. Proposed texts are not binding, although during the time they are proposed they can sometimes influence interpretation. After there is a new final text, however, the proposed text cannot be relied upon.

Statutes, Regulations, and Agency Documents

- The U.S. Constitution. The U.S. Constitution, as the highest legal document of our republic, governs everything. It may seem like it does not come up, as a practical matter, in the daily life of legal interpretation and regulatory reading, but it does. For example, under the U.S. Constitution, no federal agency has “inherent powers.” There is no such thing. The U.S. Constitution, as ratified, delegates specified powers to the federal government. Under the separation of powers among the three branches of the federal government, a federal banking agency has only the powers that Congress has delegated to it and no more. These are broad powers, but they are not limitless. Two concrete examples might help. The banking agencies have often asserted in multiple fora their authority to regulate banking organizations for safety and soundness. That power exists but is not part of any “inherent authority,” as has apparently mistakenly been taught to a generation of examiners. Rather, it comes from a Congressional statutory delegation of authority and is limited by the words contained in, and the Congressional intent behind, that authority.[8] Another recent example is the criticism and pushback from some examiners on lobbying by banking organizations. As Vice Chairman for Supervision Quarles expressed in a surprised and shocked response to a Congressional question, such behavior, if it happened, would be a clear violation of First Amendment rights to free speech and to petition the government for the redress of grievances.[9] Both examples illustrate more than anything else flaws in training and education at the agencies, which in many respects may stem from a shortage of lawyers at those agencies as well as a lack of adequate resources given to the legal budget within the agencies.

- Federal Statutes and Federal Regulations. Federal statutes and regulations are key to any legal interpretation. Statutes are bound by the limits of the U.S. Constitution. In addition, regulations cannot go beyond the authority granted by the relevant statute and must be interpreted in light of the applicable grounding statute (typically title 12 in the banking context), other applicable statutes (most commonly the Administrative Procedure Act and the Freedom of Information Act, but many others also apply), and any court cases interpreting the regulatory text or similar regulatory text from another context. Many regulations do not repeat the entire statutory text, and both must be mastered and read together in order to interpret a regulation. A good example is Regulation W in which certain defined terms are found only in section 23A or 23B of the Federal Reserve Act, so reading the regulation alone is misleading and incomplete. Regulations are issued under the notice and comment procedures of the Administration Procedure Act and are legally binding upon both the banking agency and the banking organization. Astoundingly, confusion has arisen among some risk and compliance professionals who claim that the “law” is for the lawyers, and “regulations” are for risk and compliance. This confusion is an unintended and unfortunate misunderstanding of the agencies’ admirable use of the simplified phrase “law and regulations.” A more precise, technical wording would be “the Constitution, all applicable statutes whether federal or state, all relevant judicial interpretations, and regulations.” We can all agree that “laws and regulations” is a more elegant and simplified phrase, but it does not change the fact that regulations are part of the law—that is, the legal framework. No one should be confused that regulations are not part of the law or think that they are separate from the hierarchical legal framework.

- Federal Consent Orders. Federal consent orders are binding on an individual banking organization and thus form a type of binding contractual obligation that is legally enforceable in a court. Many large banking organizations have at least one active consent order outstanding. Before giving any legal advice to a banking organization, it is necessary to confirm there is no relevant outstanding consent order. Consent orders of one banking organization are not binding on any other banking organization. Remediation plans under a consent order, once accepted by the banking agency, form part of that binding contractual obligation and are typically not public.[10]

- Federal Public Written Guidance. There has been much discussion lately about federal public written guidance, which encompasses those public agency writings that are labeled as “guidance” as well as supervisory letters, examinations manuals, and FAQs—essentially any public writing by the regulatory agency staff.[11] Banking organizations, like other regulated entities, actively seek public written guidance. Most guidance is not legally binding and is not enforceable against the agency staff or banking organizations, although in practice, many agency staff and banking organizations have, until recently, treated guidance as if it were binding.[12] Under title 12, there is also an unusual category of “enforceable guidance” or “standards” that are permitted under the statutory safety and soundness authority.[13] The OCC’s risk management guidelines fall into this category.

- There has been some confusion by certain regulatory readers asserting that guidance is not part of the legal framework and therefore does not involve legal interpretation. An understanding of the full legal framework shows this view to be deeply mistaken. The interpretation of public written guidance is part of the legal framework even if written by the agencies’ supervisory staffs, and even if it is legally nonbinding. It must be interpreted in light of the Constitution, statutes, regulations, and case law that sit above it and either infuse the interpretation or limit its applicability. Public written guidance is especially sensitive because it is explicitly meant not to apply to all situations at all times. The tyranny of the spreadsheet checklist within most banking organizations has meant that this important fact is easily lost in the realm of project management implementation.[14] It is also the situation, due to constraints of budget, resources, and stature within the agency, that public written guidance, especially the types that are published without notice and comment review, have not been truly vetted by the agency legal staffs. As a result, there is a higher incidence of errors under the legal framework in such guidance.[15] This lack of internal vetting by agency legal staff does not, however, render public written guidance as not part of the overall legal framework.[16]

- Federal nonpublic guidance and secret lore. Federal nonpublic guidance and secret lore comes in multiple forms, none of which are legally binding but which nonetheless impact the behavior of banking organizations. Much of this guidance is written, but some of it is oral. Some of this nonpublic guidance applies, like a consent order, only to a single banking organization. For example, examinations, feedback letters, MRAs, and MRIAs are all written and have the imprimatur of having been vetted by the higher levels within the banking agency.[17] Each one of these, however, to the extent it is legally infused, such as supervisory views on whether the banking organization is complying with the legal framework, in practice requires the backdrop of the legal framework of laws, regulations, and public guidance and must be read against those authorities. To complicate matters further, some examinations, consent order feedback letters, and MRAs are done on a horizontal basis across all or a subset of banking organizations.

- Banking organizations also receive nonpublic oral guidance, sometimes from individual agency staff. Much but not all of this nonpublic guidance is legally infused. An oral tradition, often called “lore” of how the legal staffs of the banking agencies interpret a certain statute or regulation, often also impacts its interpretation, especially at the Federal Reserve. This lore can change when personnel changes but has traditionally been taken quite seriously by bank regulatory lawyers when it comes from, or is attributed to, the general counsel. An example is the so-called teardown rules created by the Federal Reserve legal staff for the breaking of a controlling influence as an investment is sold. These are not “rules” at all but a series of oral principles, not made public nor written down, but which reflect the views of some legal staff at a moment in time. It is also often the case that individuals in the supervisory staff sometimes engage in interpretations of the legal framework on an oral basis. Nonpublic written guidance must be interpreted in light of the statutes and regulations that govern it. Secret lore and oral guidance that is legally infused has a troublesome placement in the legal framework because the concept of secret law in a democracy is on shaky ground. Moreover, to the extent it comes from individual conversations with individual supervisory staff and is not applied horizontally across multiple banking organizations, it may or may not have been vetted or approved by senior supervisory staff or agency lawyers.[18]

- Banking Organization Policies. Banking organizations have many policies. Some of these policies reflect the requirements of the legal framework, but many are designed to go above and beyond the requirements of the legal framework and impose a higher standard. Whether they reflect the legal framework or go beyond it, policies must be interpreted in light of the legal framework and updated when the legal framework changes.

- The legal framework and its hierarchy are a core knowledge base in the interpretation of any regulatory text, be it a statute, a court case, a regulation, or other agency document. Without a firm grasp of exactly how it applies in any situation requiring interpretation of the text, an accurate interpretation cannot be certain.

Agency Websites and What Is Law?

Now that the hierarchy of the legal framework has been explained, where and how does one find valid textual sources of the legal framework? This article is too short for an explanation of which statute and regulation sits where and with what agency, especially since many excellent explanations exist.[19] Instead, this article will deal with the use and misuse of banking agency websites, which in today’s world of easy internet access is the first stop for many. As internet use has expanded, the federal banking agencies have expanded the quality and quantity of what they label in simplified English shorthand to be the “laws and regulations” that are posted and updated on their websites. This expansion of website access is deeply admirable and has vastly expanded public access to the legal framework. The author relies upon them with gratitude nearly every day; there are, however, some tricks and traps in relying solely on banking agency websites that can make them either highly misleading or incomplete in some crucial areas.

The first misleading element is the short-hand and lovely simplified phrase, “laws and regulations,” which is widely used on banking agency websites and in consent orders. As noted above, the phrase has led some to mistakenly believe that “regulations” are somehow separate from “law” and that the interpretation of regulations does not involve legal interpretation. Nothing could be further from the truth. Regulations are binding law and part of the legal framework. Those who have come to believe that they are somehow not legal or not law need to change their mindset.

The content of the agency websites has also led to some confusion about what the “law” is that might apply to banking organizations because the websites often do not include the grounding statutes upon which the regulations, guidance, and supervisory letters are based. Only the FDIC to its immense credit posts the federal banking statutes on its website. But the reader must beware that sometimes the statutes are incomplete.[20] The Federal Reserve, the OCC, and the CFPB post only their own regulations, guidance, and supervisory letters but, quite amazingly, skip the foundational banking statutes on which their regulations, guidance, and supervisory letters are grounded. Only the FDIC posts the Administrative Procedure Act and the federal criminal laws applicable to banking organizations on its website. Other applicable federal statutes, or even the fact that they might exist, are absent from the other banking agencies’ websites. None of the federal banking agencies post or refer to the Congressional Review Act or to the recent OMB memorandum.[21] There is an easy fix to this misleading element, which is that the other banking agencies could follow the FDIC’s lead and also include their grounding statutes on their websites, as well as links or references to other applicable federal statutes.

The second misleading element is that the structuring of the topics on the agency websites also lends itself to confusion about the hierarchy of the legal framework. Here are some random examples. On the FDIC website, the statutes are treated as a subtopic of “policy,” and enforcement orders are a subtopic of “examinations.” The Federal Reserve’s website on the Volcker Rule mentions the statute, not the regulations, and the materials under the Volcker Rule topic do not contain a link to either the statutory text or the Federal Reserve’s own implementing regulations of the statutory text.[22] The OCC categorizes its handbook for recovery under the “Laws & Regulations” section of its “Publications” topic when recovery planning comes from guidance, and a handbook cannot be a law or a regulation. The CFPB categorizes rulemaking and enforcement under the topic of “Policy and Compliance.” It is no wonder that young, digital-native lawyers and regulatory readers become confused about the hierarchy of the legal framework.

The third misleading element is that the federal banking agencies’ websites are not updated for statutory changes or judicial decisions that can change the reading of the regulation dramatically. For example, the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act[23] changed the statutory text of the Volcker Rule. The Volcker Rule implementing regulations, even in their newly proposed form, do not take into account any of the statutory changes that are immediately effective. As another example, the CFPB’s website is silent about the developing circuit split around its constitutionality. The OCC website topic on “Legislation of Interest” has not been updated since 2010. The websites are also unclear about when state law might apply.[24] Finally, many older interpretations are still not available on the websites, and it remains necessary to consult with old-fashioned paper files, some of which are nonpublic or quasi-public. Determining when state law is preempted by federal law is driven by case law as well as statutory law and regulations, and is often not made obvious on the agency website.

Some of these misleading elements could be fixed by changes to the websites, but some are harder, indeed very difficult, to change by simple and sustainable improvements to the agency websites. Instead, lawyers and regulatory readers will have to remain alert to the broader context when relying upon agency websites for their work. It is also important to understand that agency websites are not neutral; their mission is to reflect the views of the agency and, just like newspapers, they are slanted in that direction by what they choose to cover and by what they choose not to cover. The agency websites are wonderful tools and destined to get better over time,[25] but as the preceding discussion makes clear, naive internet searching on an agency website or elsewhere cannot be the end of the task. It is still necessary to determine where the text fits within the hierarchy of the legal framework, whether it is still valid, and whether sources outside of the agency websites might also influence the reading.

Legal Reading Is Not Ordinary Reading

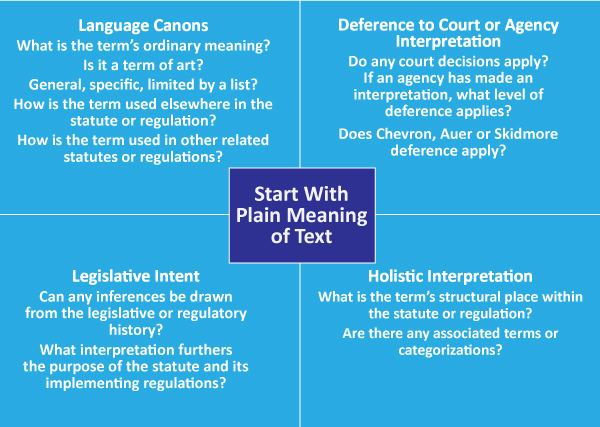

The final way in which young, digital-native lawyers and regulatory readers can be tricked is that legal interpretation is not like ordinary reading. The federal banking agency websites do not contain any of the principles of legal interpretation that make the reading of legal texts different from reading nonlegal texts. There is no mention of the canons of statutory or regulatory construction[26] and no mention of the different levels of deference to be paid to different types of agency documents. Many young lawyers and regulatory readers are unaware, for example, that statutes and regulations must be read structurally as a whole; that regulations issued under the Administrative Procedure Act, and some interpretations where the agency has special expertise, get a high level of deference under the judicial Chevron doctrine;[27] but that many other agency documents, such as guidance, FAQs, exam manuals, and supervisory letters are subject to a much lower level of deference under another doctrine, as discussed in more detail below.[28] The agency websites do not contain the basic elements of legal interpretation because no one could have anticipated when they were first created that these websites would become the first stop for those seeking to understand laws, regulations, and guidance. It is a common error of regulatory readers and young lawyers to read from the bottom up—that is, to begin with the guidance, then move to the regulation, and then to the statute. In reality, the reading should be top down, beginning with the statute and then moving to any regulation or guidance. Those who have had no training in the legal framework often mistakenly believe that reading the guidance is sufficient. Although trained lawyers should already know these principles, it is important to communicate the existence of these principles to the many regulator readers using agency websites, and even some lawyers.

The graphic below sets out the many ways in which the reading of a legal text is different from nonlegal text. One begins, of course, with the words and their plain meaning,[29] but it is never quite that easy in the legal framework of the regulatory state, which is not known for its use of plain English. To be sure, many legal interpretations are basic and simple, and the words on the page are enough. Some of these form the large areas of settled law that will, in the next few years, become more and more automated.[30] Examples of clear or settled areas ripe for automation are calculations of the days when reports are due, most of the elements of standard reports, or other repeatable events.[31] There remain, however, many areas of ambiguity, gaps, and unsettled interpretation where there is limited or no plain meaning in the text. The arena of ambiguity is quite large in the regulatory state. For that, ordinary reading is not sufficient; other tools must come into play. For example, what is “material” under the securities laws, and how does that compare to “material” under the living wills regulation? Should the same word be given similar meanings in statutory frameworks with very different goals? What is “reasonable” under “reasonably expected near term demand” under the Volcker Rule? What is “abusive” under unfair, deceptive, or abusive acts and practices (UDAAP) statutes?[32] In these areas, the tools of statutory and regulatory construction, which turn legal interpretation away from ordinary reading, must be used. There are canons of statutory construction, many of which apply in the regulatory context. This article is too short to lay them all out, but they are admirably described in excellent secondary sources.[33] The graphic below sets forth how legal interpretation differs structurally from ordinary reading.

Interpretation of a Legal Text—Not Ordinary Reading

Even language-based plain reading of a legal text, which has had more primacy in recent years than legislative history, is not identical to reading a nonlegal text. The words may be defined in the statute or regulation, or they may be defined elsewhere in other statutes and regulations and not defined in the current statute or regulation.[34] The words may be interpreted differently depending upon whether they are general or specific words, or whether they are words that appear in a list and therefore should be limited by the concepts in the list.[35] Justice Scalia has described textual analysis as “a holistic endeavor. A provision that may seem ambiguous in isolation is often clarified by the remainder of the statutory scheme—because the same terminology is used elsewhere in a context that makes its meaning clear, or because only one of the permissible meanings produces a substantive effect that is compatible with the rest of the law.”[36]

Today, these principles matter more than ever due to the cultural shift toward PowerPoint and similar applications as the dominant tool in business communications, which has led to a cultural split between those who spend their working life reading texts and those who spend their life in PowerPoint.[37] Because most official documents from regulators remain in legal or legally infused text, rather than PowerPoint, a cultural shift must sometimes be made even before engaging with the fact that reading a legal text is not like ordinary reading by the digital native.

Agency interpretations and deference are a key part of the interpretation of any legal text in the legal framework that applies to the banking sector. The banking agencies interpret the statutory text, implement the statutory text through regulations, and apply the statutes and regulations through their guidance, FAQs, supervisory letters, general counsel opinions, secret lore, and supervision. In the administrative state, the agencies have become the most important arbiters of the legal framework in most circumstances. Under various judicial doctrines, different types of agency interpretations benefit from different levels of judicial deference. These principles of deference matter, even when no judge is involved, because they inform how the legal text is read.

Under the Chevron doctrine as currently construed by the Supreme Court, when agency interpretations of statutes are made under a formal process, such as notice-and-comment rulemaking, courts defer to any reasonable agency interpretation of ambiguous statutory language.[38] When interpreting regulations, an agency’s interpretation of its own properly issued regulation is given deference unless it is “plainly erroneous or inconsistent with the regulation.”[39] For agency judgments or decisions made without a formal process, the Skidmore doctrine applies, under which courts give less deference than under Chevron, and the deference to an agency interpretation or decision in a particular case “will depend upon the thoroughness evident in its consideration, the validity of its reasoning, its consistency with earlier and later pronouncements, and all those factors which give it power to persuade.”[40] The judicial concept of different levels of deference explains, in part, why lawyers, risk managers, compliance professionals, and sometimes supervisors can talk past one another when guidance is the topic. For the trained lawyer, guidance is read with a lower level of deference, and it is not binding. For the regulatory reader, using the tools of ordinary reading with the added dollop of the tyranny of the spreadsheet of project management, it becomes literal and binding.

Conclusion

When the author began the practice of law in the late 1980s, statutes, regulations, and judicial opinions were available only in paper format. Agency interpretations were closely held secrets, often available only by FOIA requests that were routinely filed by all of the law firms with a major bank regulatory practice. Commercial, subscription-based databases became available by the mid-1990s to those lawyers at law firms willing to pay for them. Since the invention of the smartphone, however, we have lived in the era of easy internet access. Statutes, regulations, and judicial opinions can be accessed, often free of charge, by anyone from anywhere. The agencies have vastly expanded the information available on their websites, and most formal written guidance is no longer secret.[41] The age of internet access has democratized access to the legal framework so that it is no longer a small elite of regulatory lawyers who guard its gates. The pool of regulatory readers has vastly expanded. At the same time, the legal framework has become more complex, and the role of compliance with law examinations by supervisors has expanded. The rise of operational risk management in banking organizations, including within its purview operational and legal risk, along with the rise of compliance as a division separate from the legal department, have also complicated how banking organizations interpret the legal framework, sometimes leading to multiple competing poles of interpretation within the organization. At its best, the training for young lawyers on the realities of the regulatory legal framework is not core to legal education and at its worst, it is not done. For the regulatory readers, training is haphazard. The problem is exacerbated by professional silos and corporate hierarchies both within the agencies and the banking organizations. The democratization of the age of internet access has brought us many benefits, and the presence of more and better regulatory readers is a welcome development, but the haphazard and chaotic atmosphere of the internet age is not going to serve us well in the coming age of augmented intelligence. We have to get our act together if we are to find a way to appropriately train the natural-language artificial intelligence that will make the practice of law, operational risk management, and compliance work better in the coming digital age.

*Margaret E. Tahyar is a partner in Davis Polk’s Financial Institutions Group. The author wishes to thank all of her many colleagues who have commented on this article, most especially the young, digitally native lawyers and, in particular, Tyler Senackerib, who helped with the research for this piece, and Alba Baze, who helped with the research on a companion article published in January, Margaret E. Tahyar, Are Banking Regulators Special? (Jan. 1, 2018), as well as on a related comment letter to the FDIC. Comment Letter in Response to Request for Information on FDIC Communication and Transparency from Margaret E. Tahyar, Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP (Dec. 4, 2018). This article reflects the views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the views of Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP.

[1] In a companion article to be published later, I will discuss the relationship between trained lawyers and regulatory readers in the agency and corporate setting.

[2] My testimony before the Senate Banking Committee makes some suggestions for better training of the supervisory staff. Guidance, Supervisory Expectations, and the Rule of Law: How Do the Banking Agencies Regulate and Supervise Institutions?: Hearing Before the United States Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs (Apr. 30, 2019) (statement of Margaret E. Tahyar).

[3] A recent memo written by two former Federal Reserve staffers has pointed out that training on the legal framework has been delegated to the regions. Richard K. Kim, Patricia A. Robinson & Amanda K. Allexon, Financial Institutions Developments: Revamping the Regulatory Examination Process, Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz (Nov. 26, 2018).

[4] The banking agencies have long been understood to be monitor- or examiner-dominated in their personnel. Based on research by an academic, some of which is estimated, the Federal Reserve is 95-percent monitor staff, the OCC is 93-percent monitor staff, and the FDIC is 86-percent monitor staff. Rory Van Loo, Regulatory Monitors, 119 Columbia L. Rev. 369, 438–39 (2019). The higher proportion of lawyers at the FDIC is likely linked to its work as the deposit insurer and bank failures. There are simply not enough lawyers at the agencies, in comparison with the supervisory staff, for either deep training to have occurred or for there to be a thick enough pool of talent to deal with the many legally infused questions that must arise in the context of supervisory activities.

[5] The article is meant as a fill-in to some common gaps in the knowledge base of newly minted, digital lawyers and experienced regulatory readers that I have observed in my work as a part-time adjunct professor and regulatory lawyer. It is not meant to be an overall basic training, which is beyond the scope of this short piece.

[6] Leo E. Strine, Jr., Keynote Dialogue: “Old School” Law School’s Continuing Relevance for Business Lawyers in the New Global Economy: How a Renewed Commitment to Old School Rigor and the Law as a Professional and Academic Discipline Can Produce Better Business Lawyers, 17 Chapman L. Rev. 137, 150–51 (2013).

[7] For an excellent academic piece describing the role of supervision in the regulatory state, see Rory Van Loo, Regulatory Monitors, 119 Columbia L. Rev. 369 (2019).

[8] 12 U.S.C. § 1831p-1.

[9] Semi-Annual Testimony on the Federal Reserve’s Supervision and Regulation of the Financial System, 115 Cong. 86 (2018) (statement of Randal K. Quarles, Vice Chairman for Supervision). “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech . . . or the right of the people . . . to petition the government for a redress of grievances.” U.S. Const. amend. I.

[10] There are also sometimes nonpublic memoranda of understanding, board resolutions, and agreements under section 4(m) of the BHCA that would govern the behavior of a banking organization but which remain confidential supervisory information.

[11] Speeches and papers by individual agency principals or staff or congressional testimony can also inform a legal interpretation but must be treated with caution. They are not legally binding, and they may reflect a political agenda, the need for diplomatic silences in a certain political moment, or may not reflect the views of the agency as a whole, as agency principals and staff so often appropriately tell us. On the other hand, they may indeed reflect a considered legal interpretation. In my years of teaching, one of the clues that law schools are not yet effective in teaching how to interpret the legal framework of the regulatory state is the tendency of law students to be too credulous in their willingness to suspend disbelief around speeches and testimony. Read and interpret with caution.

[12] There are also many open questions at the moment about which guidance is effective if it falls into the category of guidance that ought to have been sent to Congress under the Congressional Review Act but was not.

[13] 12 U.S.C. § 1831p-1.

[14] One side effect of relying too heavily on regulatory readers, combined with checklist spreadsheets, is that banking organizations are sometimes pushed to do more than necessary because the nuances of guidance are lost.

[15] See Semi-Annual Testimony on the Federal Reserve’s Supervision and Regulation of the Financial System, 115 Cong. 86 (2018) (statement of Randal K. Quarles, Vice Chairman for Supervision) (“And with respect to our guidance, I think that we can be [more accountable for guidance] . . . , which sometimes in the past—that is less than the case of the recent past, but sometimes in the past has—has just gone out to the examiners and the banks.”).

[16] This lack of vetting is likely the result of a shortage of lawyers on the staffs of the agencies as compared to their supervisory staffs. See Rory Van Loo, Regulatory Monitors, 119 Columbia L. Rev. 369, 438–39 (2019) (Lawyers make up 7 percent, 14 percent, and 5 percent of the staffs of the OCC, FDIC, and Federal Reserve, respectively).

[17] MRAs are “Matters Requiring Attention,” and MRIAs are “Matters Requiring Immediate Attention.” They are nonpublic supervisory findings that arise from examinations. Some of them will be legally infused (for example, those that arise from compliance-with-law examinations), but many will not be (for example, those that arise from credit quality concerns).

[18] My testimony before the Senate Banking Committee includes further discussion of the increasing scope of guidance and secret lore. Guidance, Supervisory Expectations, and the Rule of Law: How Do the Banking Agencies Regulate and Supervise Institutions?: Hearing Before the United States Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs (April 30, 2019) (statement of Margaret E. Tahyar).

[19] The best short treatment in banking law is the American Bar Association published book, The Keys to Banking Law: A Handbook for Lawyers (Second Edition) by Karol K. Sparks, which has a handy key for which statutes and regulations apply to which agency and lists the applicable statutes. Of course, I cannot also help but plug Financial Regulation: Law and Policy (Second Edition 2018), a textbook that I co-wrote with Michael Barr and Howell Jackson. It has been deliberately written for both law students and regulatory readers.

[20] For example, the Volcker rule statute on the FDIC website references some key definitions that appear in other statutes that do not appear on the FDIC website.

[21] Guidance on Compliance with the Congressional Review Act, M-19-14, Office of Management and Budget (April 11, 2019).

[22] The author, having lived through the implementation of the Volcker Rule (statute and regulations, together) is immensely grateful that the Federal Reserve has a separate topic heading on its website for its supervisory guidance under the Volcker Rule and uses it often. Given how the Volcker Rule developed, it is completely understandable. The point here, however, is that the lack of attention to the hierarchy of the legal framework is a structural problem on the agency websites and leads to confusion among regulatory readers and the digitally native lawyers.

[23] The Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act of 2018, Pub. L. No. 115-174.

[24] Banking organizations are also subject to state laws in various ways. A state-chartered bank is governed by the state law of its chartering authority, but even national banks are subject to many state laws. State trust law, for example, is embedded into the trust powers of national banks. State law is also applicable under many consumer protection statutes.

[25] See, e.g., Request for Information on FDIC Communication and Transparency, 83 Fed. Reg. 50,369 (Oct. 5, 2018).

[26] Larry M. Eig, Statutory Interpretation: General Principles and Recent Trends, The Congressional Research Service (Sept. 24, 2014). See also Antonin Scalia & Bryan A. Garner, Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts (2012); William Eskridge, Legislation and Statutory Interpretation (2007).

[27] Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. NRDC, 467 U.S. 837 (1984). With changes in the Supreme Court, the Chevron doctrine is coming under question and may change.

[28] See Skidmore v. Swift & Co., 323 U.S. 123 (1994).

[29] See Moskal v. United States, 498 U.S. 103, 108 (1990) (“In determining the scope of a statute, we look first to its language, giving the words used their ordinary meaning” (internal quotations omitted)).

[30] There is also settled law via judicial interpretation where the plain meaning of the text is not enough.

[31] My assertion is not that they are perfectly clear, but that many are clear enough and could soon be automated or partly automated.

[32] See, e.g., 15 U.S.C. § 45.

[33] Larry M. Eig, Statutory Interpretation: General Principles and Recent Trends, The Congressional Research Service (Sept. 24, 2014). See also, Antonin Scalia & Bryan A. Garner, Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts (2012); William Eskridge, Legislation and Statutory Interpretation (2007).

[34] The Volcker rule regulations are an example. The concept of “debt previously contracted” appears in the National Bank Act and has a long history of public written interpretation by the OCC and, to a lesser extent, the Federal Reserve. It is not defined in the Volcker Rule regulations. Likewise, the term “investment adviser” appears in the Volcker Rule regulations. It is defined in the 1940 Act, but there is no cross-reference in the Volcker Rule regulations to its similar usage. Another example is the SEC’s proposed rules for segregation of collateral for security-based swaps. Although the proposed regulations for segregation will contain some of the technical segregation requirements, the basic requirements are found only in the Exchange Act, including for example, a reporting requirement that is mentioned nowhere in the proposed regulations.

[35] “Where general words follow an enumeration of specific items, the general words are read as applying only to other items akin to those specifically enumerated.” Harrison v. PPG Indus., Inc., 446 U.S. 578, 588 (1980). For example, if the term “fruit” is defined as “apples, bananas, oranges, or similar foods,” one could reasonably consider pears a fruit that is a “similar food” but not pizza. The question of whether a tomato, which scientists classify as a fruit but most people view as a vegetable, would fall within the “or similar foods” category would depend upon the overall context and intent.

[36] United Savings Ass’n v. Timbers of Inwood Forest Associates, 484 U.S. 365, 371 (1988) (citations omitted).

[37] PowerPoint, with its ability to communicate with visual tools, is a wonderful medium. Davis Polk’s Financial Institutions Group uses it frequently.

[38] Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. NRDC, 467 U.S. 837 (1984); Christensen v. Harris County, 529 U.S. 576 (2000); United States v. Mead Corp., 533 U.S. 218 (2001).

[39] Auer v. Robbins, 519 U.S. 452, 461 (1997) (quoting Bowles v. Seminole Rock & Sand Co., 325 U.S. 410, 414 (1945)).

[40] Skidmore v. Swift & Co., 323 U.S. 134 (1944).

[41] There still exists a wide realm of secret lore and, as I have argued elsewhere, too wide a realm of confidential supervisory information. Margaret E. Tahyar, Are Banking Regulators Special? (Jan. 1, 2018); see also, Guidance, Supervisory Expectations, and the Rule of Law: How Do the Banking Agencies Regulate and Supervise Institutions?: Hearing Before the United States Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs (April 30, 2019) (statement of Margaret E. Tahyar).