1. Introduction

As digital transformation progresses, large and established corporations, but also medium-sized companies, are increasingly coming under competitive and innovative pressures. Start-ups are developing disruptive business models, which are competing with traditional models or even threatening to replace them. The former needs access to innovation and the latter needs investment, providing a mutually beneficial opportunity for corporate venture capital (CVC) to provide a solution, giving traditional companies access to the newest innovation on the market (a so-called “window on technology”).

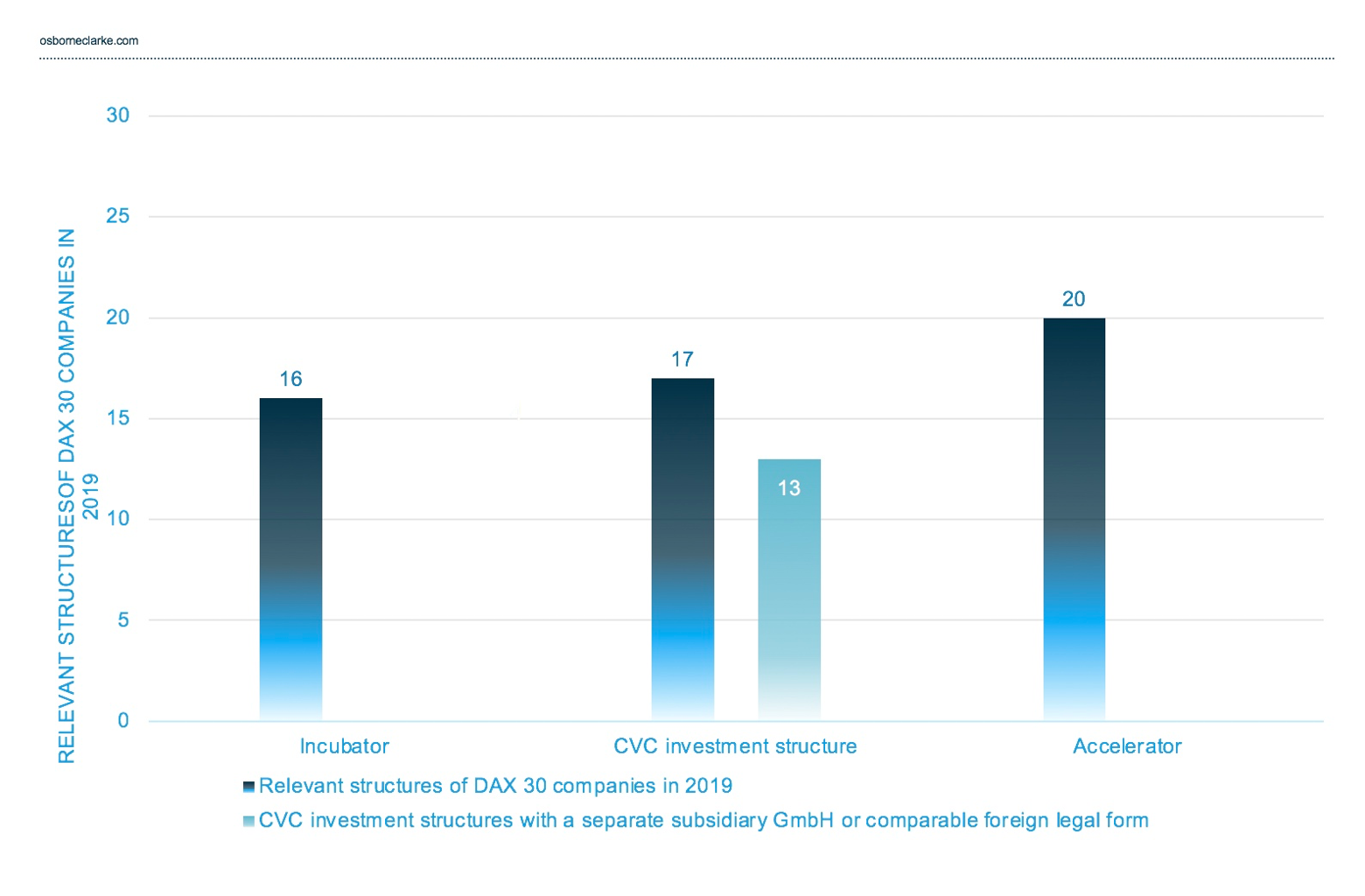

According to the 2018 Global CVC Report, there were 2,740 deals with a combined value of USD 53 billion throughout 2018 worldwide. These investments were often limited to seed and Series A financing due to the smaller financial resources of most CVC units compared to traditional VC investors.[1] Nevertheless, CVC investments accounted for around 23% of all investments in start-ups worldwide in 2018.[2] Compared to the global market, Germany still plays a limited role with only 5.3% of all deals in the years 2000 to 2018.[3] However, Germany’s largest publicly traded companies, the DAX30, now offer start-up and innovation programmes and have established their own CVC units.[4] As a result, the number of CVC investments in Europe in the first half of 2019 rose to 426 deals with a volume of EUR 6.1 billion, while the volume of CVC investments in Europe was at EUR 8.8 billion for the whole year of 2018.[5]

The term CVC covers three types of participation and cooperation between large and medium-sized companies and start-ups. In addition to the CVC unit participating in a classic venture capital fund and setting up of incubator or accelerator programs, the most common model found on the market is direct or indirect equity participation or, often, debt financing of start-ups by the respective CVC company. According to a survey by Tilburg University, 58.5% of all start-ups already work with corporations and medium-sized companies.[6]

In this article, we discuss the various possible legal structures for CVC units to participate in start-ups from a corporate and tax law perspective. We also look at the legal challenges in implementing corporate governance at the target company.

2. Possible business structures as a starting point for participations in companies

There are various legal structures for participating in suitable target companies. Participation can occur either directly by the traditional business or indirectly through an investment vehicle, with CVC companies usually acquiring minority stakes in their portfolio companies.[7]

2.1 Direct participation

Direct participation in the target company is the simplest legal structure. The investing company acquires shares directly in the portfolio company and so becomes one of its shareholders. In Germany the portfolio company is usually a limited liability company (or GmbH: Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung).[8] As a direct shareholder, the CVC investor is entitled to all the property, administrative and control rights provided by law—which is set out in the appropriate code since Germany is governed by civil law. How much influence the CVC investor actually has in the target company depends largely on the size of its investment/shareholding. As with classic venture capital investments, subscription rights, anti-dilution protection, and liquidation preferences can be negotiated and documented.

From a tax law perspective, direct participation has advantages. Profit distributions from one corporation to another corporation are generally tax-free, provided the participation in the target company is above 10% (Section 8b paragraph 4 sentence 1 of the German Corporation Tax Act (KStG)).[9] The tax exemption also applies in principle to capital gains, although 5% of the capital gains are considered non-deductible business expenses subject to corporate tax and trade tax.[10]

Direct participation is rare in practice, as it carries disadvantages. On the one hand, there is no separate limitation of liability (the trading entity is a direct shareholder in the start-up), and direct participation is inflexible from a company’s legal perspective. On the other hand, direct participation of the CVC unit in the parent company often requires formal approvals and leads to lengthy decision processes, which is difficult to reconcile with the investment decisions to be taken and the flat hierarchical culture of a start-up. Successful CVC investment therefore usually requires a strategic reorientation of the parent company’s usual approach to corporate decisions for its core business. To achieve an agile company culture, it is usually better to consider a different separate business structure.

2.2 Indirect participation

CVC activities of traditional companies regularly occur through the formation of separate and legally independent CVC units.[11] These CVC units are not only composed of employees of the parent company, but often also of external venture capital experts. By legally separating the CVC units from the parent company, the CVC investor can act more flexibly and faster. The CVC units differ from traditional VC companies primarily because the parent company is the sole investor in the CVC company. More than 70 CVC units already exist in Germany.[12]

(1) Indirect participation through a German limited liability company (GmbH)

The participation through a GmbH is the standard model. The parent company holds 100% of the shares in the CVC-GmbH. The CVC-GmbH in turn holds the shares in the target company. The same applies to the contractual arrangement of the investment between the CVC-GmbH and the target company, as in the case of a direct participation by the parent company. The legal advantage of indirect participation is that the liability for the investment in the target company is limited to the CVC-GmbH and the separate entity provides greater flexibility under company law. The disadvantage is that the standard model creates additional taxation. However, the same comments above apply to the tax burden on the CVC-GmbH, which means that in principle, capital gains are tax-free, although 5% of the capital gains are considered non-deductible business expenses, which are taxable.[13]

The additional taxation can be compensated by forming a tax group between the parent company and the CVC-GmbH. A tax group is a taxation unit consisting of two independent companies: the controlling company and the controlled company. Both companies form a single taxpayer, so that taxes only have to be paid at the level of the parent company. The prerequisite for the formation of a tax group (pursuant to Section 14 paragraph 1 sentence 1 KStG) is the documentation of a profit and loss transfer agreement between the controlling company and the controlled company, according to which the latter undertakes to transfer its profits to the controlling company.[14] Pursuant to Section 14 paragraph 1 no. 3 sentence 1 KStG, the profit and loss transfer agreement must be in place for at least five years and be actually implemented during this period.[15]

(2) Indirect participation through an investment company (German: Unternehmensbeteiligungsgesellschaft (UBG)).

Indirect participation is also possible through an investment company. A UBG must be recognized as such by the competent authority according to Section 1a paragraph 1 of the Investment Companies’ Act (UBGG). It can also be operated in the legal form of an AG, GmbH or KGaA (Kapitalgesellschaft, orlimited liability company). The UBGG does not create a new legal structure of its own but refers to certain already existing business structures. The UBGG offers tax advantages: If recognised, the UBG is exempt from trade tax under Section 3 No. 23 of the German Trade Tax Act (GewStG). Apart from that, however, the normal corporate tax regulations apply, as long as the UBG is organised in the legal structure of a GmbH or AG (Aktiengesellschaft, or stock company).[16]

The UBGG regulates certain investment and participation limits. A distinction is made between open and integrated investment companies. Unlike the integrated UBG, the open UBG can only be organized as a subsidiary of the parent company for five years (Section 7 paragraph 1 sentence 1 UBGG). In contrast, the integrated UBG may in turn only participate in companies in which there is at least one natural person entitled to manage the company and who holds at least 10% of the voting rights of the company (Section 4 paragraph 4 sentence 1 UBGG).

In practice, it is problematic that the investment company can only grant loans to companies in which it already has a stake (cf. Section 3 paragraph 2 UBGG). If the investment company does not have participation in the start-up, it will not be possible to grant the respective start-up a convertible loan, often used for early-stage financing. As a result, investment companies are rarely used in practice and mainly invest in banks, where the granting of loans to the portfolio company is often not market standard and so avoids the application of equity substitution rules.[17]

(3) Indirect participation through a GmbH & Co. KG (German: Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung & Compagnie Kommanditgesellschaft)

Another possible option for CVC participation is the indirect participation through a partnership in the form of a GmbH & Co. KG. General and limited partners do not have to be natural persons.[18] For this option, both a limited partnership (Kommanditgesellschaft) and a general partner in form of a GmbH have to be established. In this case the CVC-GmbH & Co. KG holds the shares in the target company. The parent company holds all shares in the GmbH & Co. KG and in the general partner GmbH.

The participation through a GmbH & Co. KG has several advantages over the simpler GmbH structure mentioned above:

1. flexibility under company law,

2. limitation of liability for the parent company,

3. tax transparency as a partnership and

4. the relatively simple incorporation procedure of the GmbH & Co. KG without any further requirement of notarisation.[19]

The disadvantage of this arrangement is that with the formation of the general partner GmbH and the GmbH & Co. KG, the investment structure becomes more complex and administratively complicated.

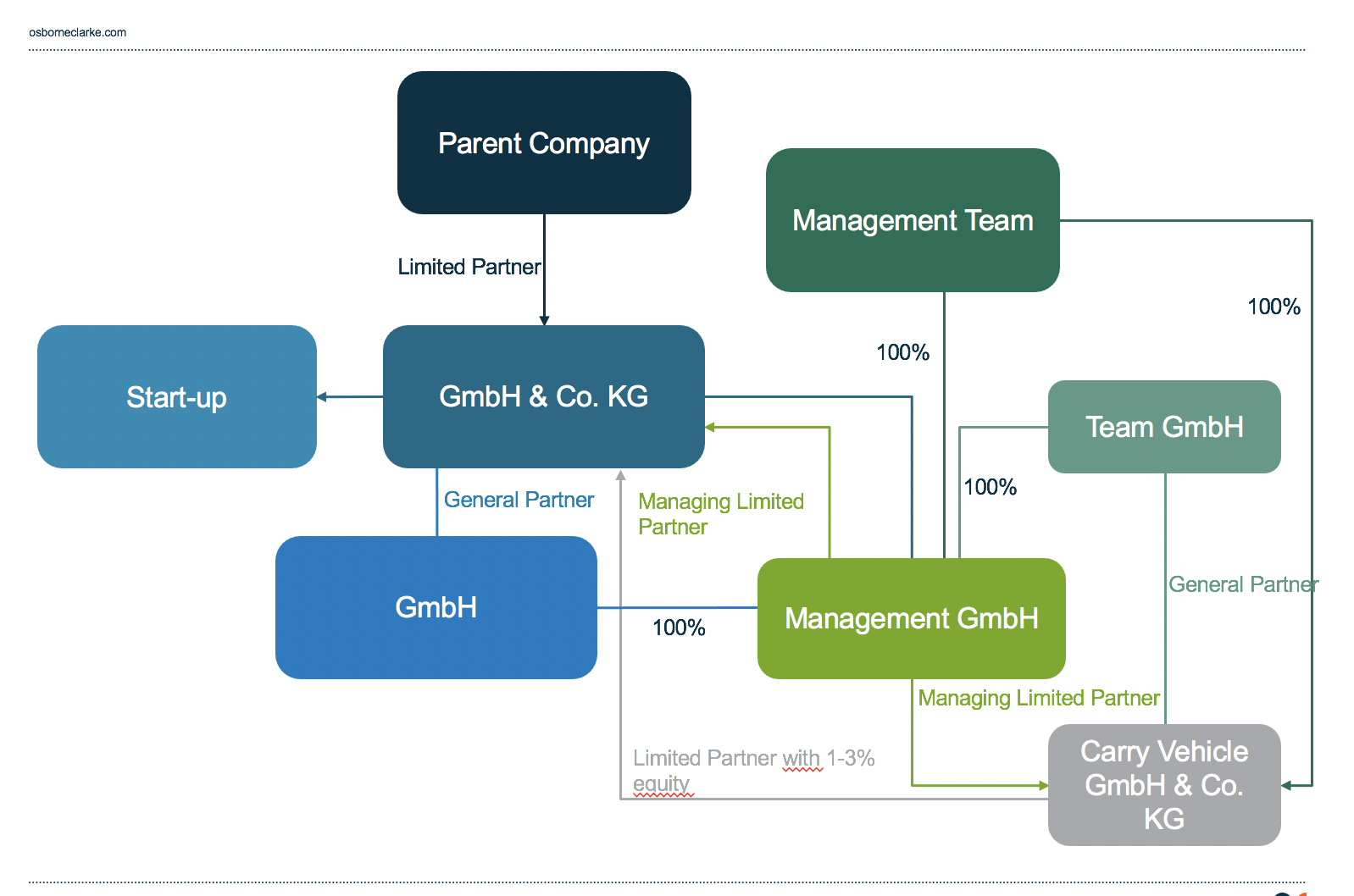

(4) Indirect participation with capital participation of the management

The most complex form of indirect participation by the CVC unit is through capital participation of the management.[20] First, the previous model, which involved an indirect participation through a CVC GmbH & Co. KG, is constructed. Only the CVC-GmbH & Co. KG alone holds the shares in the target company. However, a further company is added as a carry vehicle, in which the management team participates. This enables the profit (“carry”) to be shared individually between them. Due to the advantages described above under (3), the legal structure usually chosen for the carry vehicle is the limited partnership, as it is fiscally transparent and provides limited liability to the management.[21] The carry vehicle participates in addition to the parent company as a limited partner with a capital participation in the CVC-GmbH & Co. KG (giving it “skin in the game”).[22] The general partner GmbH does not have a share in the assets of the CVC-GmbH & Co. KG and is held 100% by the capital management company in the form of a Management GmbH, which is also the managing limited partner of the CVC-GmbH & Co. KG and the carry vehicle. The latter also makes sense from a tax perspective, as the tax authorities consider the non-trading characteristics of the CVC-GmbH & Co. KG and the carry vehicle so that no trade tax is payable.[23]

The profit participation of the management is usually disproportionate to the capital. Typically, the carry is around 20% of total earnings.[24] The fund agreement must specify the further details of profit distribution, in particular the extent to which profits from the CVC company’s investments may be retained for reinvestment and whether the parent company is entitled to any preferential return (the “hurdle rate”).[25] There are two standard models for calculating the carry: either all investments during the entire term of the fund are taken into account in the profit participation or only the individual exit is taken into account. From the point of view of the parent company, the overall view is preferable, as otherwise the management receives carry payments early on, even though later investments may be less successful, which in turn has to be compensated later after deduction of taxes (“carry clawback”). However, a payment of the carry late in the life of the investment can in turn have a negative impact on the management team’s motivation.

Ultimately, this fund structure offers the advantage that the management of the CVC unit participates in the success of the CVC company and thus creates a further incentive for the management to achieve the highest possible profits for the CVC company. At the same time, capital participation ensures that the management also participates in the economic risk of the CVC company. The “fund structure” allows a balance between the interests of the managers and the CVC investor, which cannot be achieved by a mere contractual agreement of the management team’s compensation (possibly with additional bonuses if defined targets are reached).

3. Implementation of corporate governance at the level of the portfolio company

The term “corporate governance” covers general principles of proper management. Although these principles are primarily aimed at listed companies pursuant to Section 161 of the German Stock Corporation Act (AktG), compliance with them is also recommended for non-listed companies.[26] Having said this, a CVC investor has an interest in implementing its corporate governance principles in its portfolio companies as well. After all, management within the portfolio company that is inconsistent with the parent company’s corporate governance also has a negative effect on the parent company. The following focuses on the cornerstones of implementing some of the aspects of corporate governance in the start-up portfolio company, without addressing all aspects and topics of the investment agreement.[27]

(1) Compliance, due diligence, and warranties

Any company, regardless of its size, may be subject to claims for damages and/or fines in the event of compliance violations. However, while a consistent compliance management system is usually already implemented in the parent company, the pursuit of agility in the start-up often stands initially in diametric opposition to such adoption. Fixed structures should be avoided in start-ups to speed up processes and make them more flexible.[28]

In later phases of European start-ups, however, there is a focus on issues surrounding data protection, regulation, and, increasingly, cyber security and consumer protection[29] due to the risk of potentially substantial fines. The same applies to start-up exits, where the purchase agreement of the company focuses on due diligence checks and warranty catalogues, so that the selling shareholders focus on data protection, consumer protection, and IT compliance at an early stage in order to avoid having to accept valuation adjustments or extensive exemptions later in the exit process.

(2) Advisory board and approval requirements

The formation of an advisory board has established itself as an important component of corporate governance. Most start-ups in Germany are organized as a GmbH, whose statutory bodies are limited to the management and the shareholders’ meeting. However, it is possible to set up an advisory board based on the articles of association, if included, or based on a contract (organschaftlichen oder zumindest schuldrechtlichen Beirat).[30] Both types of advisory boards can take on advisory, monitoring, or management functions. Like the management body, the advisory board can also be staffed by third parties from outside the company.[31] CVC investors secure their influence on the portfolio company by, among other things, being granted the right in the shareholders’ agreement or partnership agreement to appoint (at least) one advisory board member and/or a so-called “observer” to the advisory board. A further characteristic of good corporate governance is transparency.[32] This can be reached through the agreement of extensive information rights and obligations.

The Corporate Governance Code becomes particularly relevant when interpreting general company law clauses such as Section 43 of the German Limited Liability Companies Act (GmbHG) or Section 93 AktG. According to the Business Judgement Rule, the decisive factor is whether the respective management body has made decisions in the best interests of the company and—based on appropriate information—in a reasonable manner. This legal standard leaves a great deal of leeway for management boards and managing directors, which can be contractually limited by rights of approval. Thus, special majority requirements, veto rights of individual shareholders, and reservations of approval of the shareholders’ meeting or the advisory board are regularly found in shareholder agreements and articles of association of (C)VC-financed start-ups.

(3) Vesting

For CVC investors, it is also particularly important to commit the management of the start-up to comply with corporate governance for as long as possible.

One way to implement these requirements is to include vesting provisions in the investment agreement. Vesting is primarily implemented through the transfer of founder’s shares, subject to the condition precedent of the occurrence of a pre-defined event before the end of the vesting period, which generally lasts three or four years.

Particularly relevant in practice is the event of termination of the managing director’s service contract or the employment contract of the founder for good cause. Such reasons can be extensively negotiated and often include a (significant) violation of a code of conduct or other compliance guidelines by the founder. With no “employment at will” in Europe, such provisions need careful thought at the time of investment.

4. Summary

The indirect participation of the parent company through a participation vehicle works best for both the CVC investor and the target company. The specific form of company that should be chosen for the investment vehicle depends on the interests of the parent company. Particularly crucial is the question of whether the management should participate in the profits (and losses) of the CVC unit. Ultimately, the challenge for CVC investors is to find a form of participation that offers the greatest possible agility and enables rapid decision-making processes.

The internal corporate governance requirements of the parent company should not be too overwhelming for the start-up but should nevertheless be respected. For start-ups, it is crucial that the contribution of the CVC investor supports rapid progress and that the contractual documentation provides access to the CVC investor’s technological know-how, production and development resources, distribution channels and cooperation partners (“smart money”).

Finally, the investment agreement should ensure that the interests of all stakeholders involved (especially founders, business angels, VCs, and CVCs) are aligned as far as possible and focuses on increasing the value of the start-up.

*Robin Eyben and Maximilian Vocke are lawyers at Osborne Clarke in Berlin. Special thanks to Dana Alpar, legal trainee at Osborne Clarke, Berlin.

[1] See cbinsights under www.cbinsights.com/research/report/corporate-venture-capitaltrends-2018/, accessed on 13.1.2020.

[2] See Tilburg University, 2019 Corporate Venturing Report. Available at: www.corporateventuringresearch.org/

[3] See ebenda.

[4] See Dax 30 Startup- und Innovationsmonitor: Update 2019, under https://www.mm1.com/ch/ueber-uns/aktuelle-publikationen/, accessed on 13.1.2020.

[5] See https://pitchbook.com/news/reports/2q-2019-european-venture-report, accessed on 13.1.2020.

[6] Tilburg University, 2018 Global Startup Fundraising Survey, 2019 Corporate Venturing Report. Available under: www.corporateventuringresearch.org/.

[7] Grub/Krispenz: Auswirkungen der Digitalisierung auf M&A-Transaktionen. In: Betriebs-Berater, 2018, p. 235-239 (236).

[8] In later phases, start-ups are also organised in the legal form of an Aktiengesellschaft (AG) or Societas Europaea (SE).

[9] Schulz: § 11 Die Ertragsbesteuerung der GmbH und ihrer Anteilseigner. In: Beck’sches Handbuch der GmbH, 5. ed., Munich, 2014, no. 270.

[10] Schulz: § 11 Die Ertragsbesteuerung der GmbH und ihrer Anteilseigner. In: Beck’sches Handbuch der GmbH, 5. ed., Munich, 2014, no. 271. This taxation privilege does not apply to credit institutions and financial services institutions (§ 8 b VII S. 1

KStG).

[11] Klamar/Prawetz: Corporate Venture Capital Markt in Deutschland, Frankfurt am Main, 2018.

[12] BVK-Statistik: Zahl der Woche: Mehr als 70 CVC-Gesellschaften in Deutschland, 25.03.2019. Available under: https://www.bvkap.de/events-medien/videos/2019-03-25/zahl-der-woche-mehr-als-70-cvc-gesellschaften-deutschland.

[13] This taxation privilege may also not apply to credit institutions and financial services institutions at the CVC-GmbH level (§ 8 b Abs. 7 S. 2 KStG).

[14] Ebber: KStG § 14 Aktiengesellschaft oder Kommanditgesellschaft auf Aktien als Organgesellschaft. In: BeckOK KStG, Micker/Pohl, 3. ed., München, stand: 15.09.2019, no. 349.

[15] Premature termination, meaning before the end of the five-year period without good cause, results in invalidity from the outset, so that any profits are taxable retroactively at the level of CVC-GmbH.

[16] Veith: § 17 UBGG (Gesetz über Unternehmensbeteiligungsgesellschaften). In: Private Equity und Venture Capital Fonds, Pöllath/Rodin/Wewel, Munich, 1. ed., 2018, no. 13.

[17] Veith: § 17 UBGG (Gesetz über Unternehmensbeteiligungsgesellschaften). In: Private Equity und Venture Capital Fonds, Pöllath/Rodin/Wewel, Munich, 1. ed., 2018, no. 21.

[18] Roth: HGB § 161 [Begriff der KG; Anwendbarkeit der OHG-Vorschriften]. In: Baumbach/Hopt, Handelsgesetzbuch, 38. ed., Munich, 2018, no. 3, 4.

[19] See Schwarz van Berk/Euhus: § 2 Wahl der geeigneten Fondsstruktur. In: Private Equity und Venture Capital Fonds, Pöllath/Rodin/Wewel, Munich, 1. ed., 2018, no. 3.

[20] In the case of private equity funds, the fund management originally used to hold a participation of 1%, but now it is more likely to be 2-3%, see Mardini: § 11 Vergütung und Erfolgsbeteiligung (Management Fee, Carried Interest). In: Private Equity und Venture Capital Fonds, Pöllath/Rodin/Wewel, Munich, 1. ed., 2018, no. 64.

[21] Mardini: § 11 Vergütung und Erfolgsbeteiligung (Management Fee, Carried Interest). In: Private Equity und Venture Capital Fonds, Pöllath/Rodin/Wewel, Munich, 1. ed., 2018, no. 55.

[22] For the possible classification of Carry GmbH & Co. KG as an AIF or investor in an AIF see El-Qalqili/Volhard: § 4 Verwalter eines AIF (Anwednungsbereich des KAGB). In: Private Equity und Venture Capital Fonds, Pöllath/Rodin/Wewel, Munich, 1. ed., 2018, no. 39 et seq.

[23] Buge: § 25 Steuerliche Struktur des AIF. In: Private Equity und Venture Capital Fonds, Pöllath/Rodin/Wewel, München, 1. ed., 2018, no. 92.

[24] „Two and Twenty“ (2% Management Fee, 20% Carry), see Mardini: § 11 Vergütung und Erfolgsbeteiligung (Management Fee, Carried Interest). In: Private Equity und Venture Capital Fonds, Pöllath/Rodin/Wewel, Munich, 1. ed., 2018, no. 56.

[25] Due to the longer holding period, Venture capital funds often do not agree on a hurdle rate.

[26] Weitnauer: Teil E. Die Gründung. In: Handbuch Venture Capital, Munich, 6. ed., 2019, no. 338.

[27] The investment agreement of (corporate) venture capital financed companies usually contains extensive provisions on the control of the company and the economic distribution of proceeds. In many of these regulations there is an asymmetry of interests between financial investors, founders and CVCs, especially if the latter are strategically motivated. For reasons of scope and focus, the presentation of these regulations and conflicting interests as well as the practically very relevant approaches to solving this problem is not subject of this article.

[28] Federmann/Hensel/Krause: CB-Beitrag: Compliance bei Corporate-Venture-Capital-Transaktionen. In: Compliance-Berater, 2019, p. 248-253 (250).

[29] So-called Omnisrichtlinie, see www.consilium.europa.eu/de/press/press-releases/2019/03/29/eu-to-modernise-law-on-consumer-protection/, accessed on 13.1.2020.

[30] Heermann: GmbHG § 52 Aufsichtsrat. In: GmbH-Gesetz, Ulmer/Habersack/Löbbe, Heidelberg, 2. ed., 2014, no. 316. Uffmann: Überwachung der Geschäftsführung durch einen schuldrechtlichen GmbH-Beirat? In: NZG, 2015, p. 169-176.

[31] Spindler: GmbHG § 52 Aufsichtsrat. In: Münchener Kommentar GmbHG, Munich, 3. ed., 2019, no. 733.

[32] See no. 6 of the German Corporate Governance Code (In the version of February 7, 2017 with decisions taken at the plenary session of February 7, 2017). Available under: www.dcgk.de/de/kodex.html.