Introduction

On December 24, 2020, after four years of extensive negotiations, the European Union (EU) and the United Kingdom (UK) reached an agreement in principle on a EU-U.K. Trade and Cooperation Agreement in an eleventh hour effort to avoid a “no-deal Brexit.” The UK had departed the EU in January 2020 following conclusion of the Withdrawal Agreement.[1] The Withdrawal Agreement included an 11-month transition period, during which the UK agreed to continue to apply EU law and procedure, and, except for participation in EU institutions and governance, the EU continued to treat the UK as if were a member state (and not as a third country). The transition period, which expired on December 31, 2020, was intended to give the UK and EU time to negotiate a framework for future cooperation.

If, as seemed likely as recently as early December 2020, no acceptable[2] trade agreement were concluded by the deadline at year-end, then the U.K. and the EU would have had to fall back on default World Trade Organization (WTO) rules[3] to manage their economic ties. With respect to goods, this would have led to imposition of fresh tariffs and a variety of border controls and new customs duties entering into force on January 1, 2021. Based on prevailing terms, exports from the EU to the UK would have been subject to an average 3.1 percent tariffs and 1.4 percent “nontariff barriers.” There would also have been 3.3 percent tariffs on goods going from the UK into the EU and the European Economic Area (EEA).[4] The major impact, however, would have been felt on cars and agricultural goods, which would have been subject to 10 percent more, and dairy products, which would have been subject to an additional 36 percent.

In connection with legal services in a no-deal Brexit, from and after January 1, 2021 the EU regulatory framework allowing UK law firms and lawyers to provide services and/or establish and practice in EU member states would simply have evaporated. Instead of being subject to a single EU-wide legal framework, UK lawyers and law firms would be subject to myriad rules and regulations in each of the 27 EU member states and ultimately would only be entitled to those rights granted by the national regulators in those states to “third country” (i.e., non-EU) lawyers.

From the EU’s perspective, the free trade agreement (FTA) with the UK was the most important agreement they had to negotiate. Their hope was to use the EU-Japan and EU-Canada FTAs as models. The European Commission would also address the ability of individual EU member states to reach bilateral agreements with the UK.

Notwithstanding negative prognostications in the media, negotiation of a UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement (the “Agreement”) was successfully concluded, to much fanfare and jubilation, on Christmas Eve. The representatives of the EU member states have agreed to provisional application of the Agreement beginning January 1, 2021, but, in order to have long-term binding status, the Agreement must be ratified by the Council of the EU, the European Parliament and the U.K. Parliament.

Some “Cheerful Facts”[5] About Lawyering in the UK

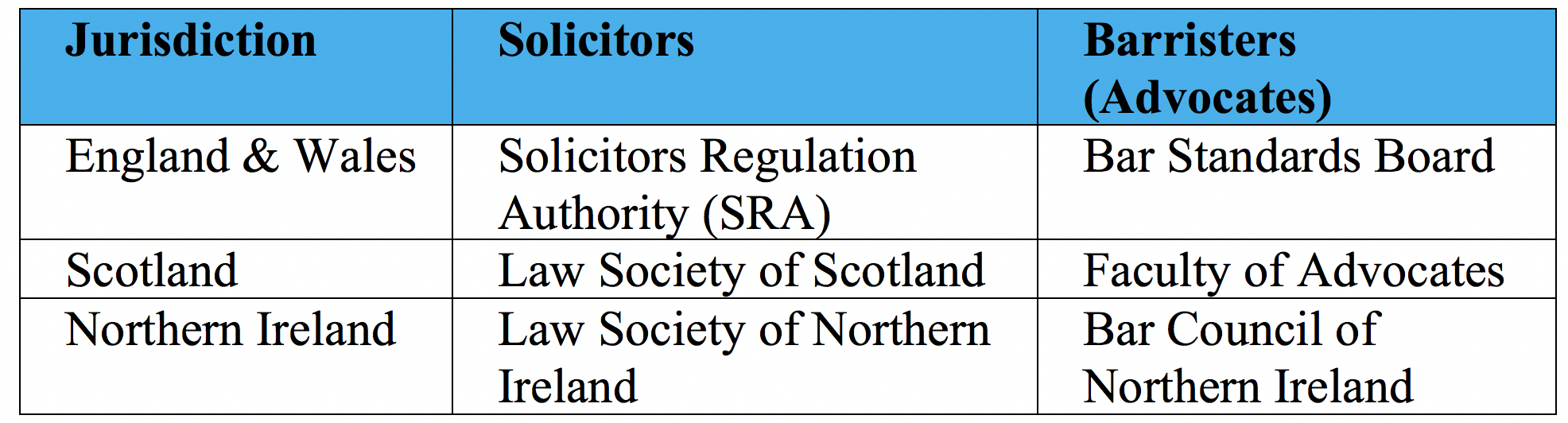

Three separate jurisdictions comprise the UK — England and Wales (jointly), Scotland, and Northern Ireland — each of which divides the practice of law between solicitors and barristers (the latter known in Scotland as “advocates”). Regulation of the legal profession is likewise subdivided:

Foreign lawyers (including U.S. lawyers) practicing in the UK are required to register in some capacity with only one of these authorities (known as “competent authorities”), though it is permissible to register with more than one provided they regulate the same group (either solicitors or barristers/advocates). One cannot, however, be registered simultaneously with one of the bodies regulating solicitors and one of the bodies regulating barristers. Upon registering with a competent authority, a foreign lawyer acquires rights of practice similar to that legal profession in that jurisdiction (including the right to do the work reserved to the local profession, subject to certain restrictions in specified proceedings); likewise, the foreign lawyer becomes subject to the rules, regulation, and discipline of that competent authority.

Thus a U.S., European,[6] or other non-UK lawyer wishing to practice transactional or regulatory law in London would likely want to register with the SRA. Were that lawyer to register, instead, with the Law Society of Scotland, he or she would only be able to perform the subset of legal work that Scottish solicitors are permitted to do in England and Wales.

When the UK was part of the EU, a number of community-wide directives, layered atop the Legal Services Act 2007 (LSA)[7] and the SRA’s implementing standards and regulations, applied to British regulation of EU lawyers practicing in the U.K. These edicts included:

(1) the Council Directive of 22 March 1977 to facilitate the effective exercise by lawyers of freedom to provide services (77/249/EEC), prescribing the rights of EU lawyers to practice on a temporary basis in other member states under their professional titles; and

(2) the Lawyers’ Establishment Directive,[8] prescribing the rights of lawyers who, in general, (A) are licensed in a member state of the EU, (B) are EU nationals, and (C) comply with the requirements for practicing in the UK[9] on a permanent basis under their home professional title (e.g., a Rechtsanwalt in Austria, an avocat in France, a Δικηγόρος in Greece).

Similarly, UK lawyers who practiced in EU member states enjoyed an array of privileges, including the authority to:

- establish themselves under home title in any member state;

- provide advice in both home and host country law;

- provide advice on EU law;

- provide temporary cross-border legal services, without the need to register with the host country’s bar; and

- be admitted as a lawyer in another member state, either by practicing that country’s local law (including EU law) for three years or by passing prescribed examinations, without ever establishing themselves in the other state.

Note that this congeries of practice authorizations for foreign lawyers was far broader than is available to UK lawyers in any other jurisdiction, including the United States.

All of that changed with Brexit.

The U.K. – EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement

The Agreement is complex. A summary of the Agreement prepared by Her Majesty’s Government (HMG) itself runs to 34 pages. The majority of the Agreement focuses on trade in goods, even though approximately 80 percent of Britain’s economy is based on services.[10] Judging solely by the numbers of pages involved in comparison to the total length of the Agreement, it appears that only 5 percent of the provisions dealt with trade in services. Nevertheless, a few services were accorded specific attention, and trade in legal services was one of those[11] – the only profession to merit such recognition.[12]

HMG listed this in its internal scorecard — which was publicly released just prior to finalization of the Agreement — as a victory. It is, however, the only victory on that scorecard accompanied by a footnote, and if one takes the time to pore through the document and construe the footnote, one discovers that the text giveth and the footnote taketh away.

The Agreement does not create anything more than an exoskeleton, or framework, for potential mutual recognition of professional qualifications. Similarly, there is nothing in the Agreement that would provide for the mutual recognition of court judgments. This framework, which is modeled after the EU-Canada FTA, may be elaborated in more detail in the future.

Likewise the Agreement does not provide for any harmonized, EU-wide right for UK lawyers to practice law. Rather, as of January 1, 2021, UK practitioners, like lawyers from any other non-EU country, are subject to 27 different regulatory regimes, each determining how third-country lawyers may practice within the particular jurisdiction and each with its own set of rights, obligations, and restrictions. Section 7 of Title II, Chapter 5 in Part Two of the Agreement sets forth a basic right for UK solicitors to offer in an EU member state professional services relating to their home jurisdiction law (i.e., UK law) and public international law but excluding EU law, subject to the vagaries of individualized restrictions in the aforementioned 27 regulatory regimes. Thus, as a result of Brexit, UK lawyers have lost the ability in EU member states to advise on host state law and EU law. Furthermore, those lawyers will be subject to domestic restrictions (set out in the annex to the Agreement) did not apply previously.

In short, with respect to substantive law practice, the Agreement provisions themselves do not confer anything that would not likely have been the default regulatory regime in a no-deal Brexit, to wit: the General Agreement on Trade in Services (the “GATS”).

In terms of cross-border practice, the Agreement does constitute some improvement over the default rules of the GATS with respect to independent professionals, short-term business visitors, and intra-corporate transferees. Nevertheless, the annexes refer to the ability of the 27 member states to adopt “non-conforming measures,” which might encompass a number of individualized requirements such as visas, working permits, or even economic tests.

Thus, depending on the local regulations in the countries in which a U.K. lawyer or law firm operates, an array of challenges is likely to present itself, including:

- Restrictions on providing services in EU member states on a temporary basis using home state qualification (“Fly in – Fly out” or “FIFO”).

- Restrictions on use of the UK limited liability partnership (LLP) structure.

- Loss of rights of audience[13] before the EU courts, unless a UK lawyer independently holds alternative EU/EEA (but not Swiss) qualifications.

- Restrictions on practicing with, or sharing profits or equity with, non-EU lawyers.

- Loss of the protection of the EU legal professional privilege[14] in front of EU courts and other EU institutions for communications between UK-qualified lawyers and their clients (other than for non-in-house[15] UK lawyers who have requalified as EEA lawyers).

One of the key challenges for UK law firms is structuring their international practices. As a result of Brexit, the UK is now considered a third country, which means that mutual recognition has gone by the wayside and the LLP form of business organization, common to many law firms, will no longer be honored in the EU. This inconvenience may necessitate restructuring (such as by relocating an LLP’s headquarters or converting EU offices into local partnerships or subsidiaries). Some London firms appear to have activated some of those contingency plans in advance by restructuring their LLP operations in Germany.

Following the Brexit vote, solicitors in England and Wales sought an end run around some of these issues by joining the roll of the Law Society of Ireland.[16] By becoming registered, and dual-qualified, in Ireland, UK-based lawyers and their firms hoped to be able to retain the protection of the legal professional privilege, rights of audience, ability to practice in EU countries, and FIFO rights.[17] This maneuver was sometimes referred to as the “Irish backdoor.” In November 2020, however, the Irish backdoor was firmly shut when the Law Society of Ireland announced that “only solicitors who are practising (or intending to practise) in Ireland from an establishment in Ireland will be provided with practicing certificates.” Eliminating that strategem may well lead to more UK law firms establishing offices in Ireland solely in order to avail themselves of EU practice benefits.

The French government has been more accommodating with respect to the LLP structure. According to the website of the Law Society of England and Wales, in December (i.e., prior to the Agreement), France enacted an Ordinance grandfathering the rights to practice of law firms operating in France as branches of UK LLPs. The Ordinance confirmed that even though a LLP would not be recognized as a valid legal structure in France, UK law firms that had previously established LLP branch structures in France under the EU Lawyers Establishment Directive would be permitted to continue operating using their existing structure after January 1, 2021[18] and this was so irrespective of the outcome of trade negotiations between the UK and the EU.

It will be interesting to see not only how the UK and the EU understandings about lawyer licensing are fleshed out in the coming months but also whether other EU member states enter into bilateral agreements with the UK that affect trade in legal services.

[1] Officially titled “Agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community [Euratom],” the Withdrawal Agreement is a treaty prescribing the terms of the U.K.’s withdrawal from the EU and Euratom. This treaty was a renegotiated version of an agreement that had on three occasions been rejected by the House of Commons, which led to Queen Elizabeth II’s acceptance in July 2019 of the resignation of Theresa May as Prime Minister and the accession to that post of Boris Johnson.

[2] Press accounts attributed to EU diplomats the belief that the U.K. is trying to gain an unfair advantage by asking for a zero-quota, zero-tariff deal.

[3] E.g., the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which actually was the progenitor of the WTO.

[4] The EEA is a free-trade zone created in 1994 and is composed of the EU member states together with Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein.

[5] With apologies to “I Am the Very Model of a Modern Major General” from W.S. Gilbert & A. Sullivan, The Pirates of Penzance (1879).

[6] “European” refers to countries in what has traditionally been referred to as the “Continent,” regardless of whether they are members of the EU. Lawyers hailing from one of the 27 (at current count) EU member states will be specifically referred herein to as “EU lawyers”).

[7] Enacted by Parliament in 2007 to liberalize and regulate the market for legal services, the LSA encouraged more competition and established a new mechanism for complaints by consumers of legal services. Section 1 of the LSA identified eight regulatory objectives: (1) protecting and promoting the public interest; (2) supporting the constitutional principle of the rule of law; (3) improving access to justice; (4) protecting and promoting the interests of consumers of legal services; (5) promoting competition in the provision of legal services; (6) encouraging an independent, strong, diverse, and effective legal profession; (7) increasing public understanding of the legal rights and duties of the citizenry; and (8) promoting and maintaining adherence to a set of professional principles. The latter encompassed, inter alia, acting with independence and integrity, maintaining proper standards of work, acting in clients’ best interests, and preserving client confidentiality.

[8] Directive 98/5/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 February 1998 to facilitate practice of the profession of lawyer on a permanent basis in a Member State other than that in which the qualification was obtained.

[9] For EU purposes, the UK constituted one member state, so the Directive did not affect transfers between Scotland, Northern Ireland, and England and Wales.

[10] Topics such as fisheries were apparently major bones of contention.

[11] The others were delivery, telecommunications, international maritime transport, and financial services.

[12] Considerable lobbying of HMG was done, it must be acknowledged, by the Law Society of England and Wales, with the backing of the Ministry of Justice.

[13] In the terminology of English law, a “right of audience” is akin to what is referred to in the United States as admission to practice before a particular court.

[14] The EU incarnation of this privilege has some similarities, but is not identical, to the attorney-client privilege. The scope of the EU legal professional privilege concerns communications relating to a Commission administrative or enforcement procedure. It does not concern a company’s right to withhold privileged documents from private parties or relate to other governmental authorities.

[15] The 2010 decision of the European Court of Justice in Akzo Nobel Chemicals Ltd. and Akcros Chemicals Ltd. v. Commission held that the privilege cannot be claimed with respect to communications between company employees and in-house lawyers.

[16] In anticipation of Brexit, from January 1 – November 12, 2019, 1,817 new solicitors from England and Wales had their names entered on the Roll of Solicitors in Ireland, See Allen & Overy, Linklaters and Eversheds lead race to register UK lawyers in Ireland ahead of Brexit, The Global Legal Post, Dec. 3, 2019.

[17] As the only English speaking common law jurisdiction left in the EU, Ireland has emerged as an important location for UK and other firms post Brexit.

[18] This grandfathering only applies to existing law firm structures. From and after January 1, 2021, it is no longer possible for a firm to establish a new branch of a UK LLP in France. Moreover, existing firms grandfathered under the Ordinance are not permitted to increase or transfer the ownership interest and/or voting rights held by UK entities and/or UK individuals in the branch structure after January 1.