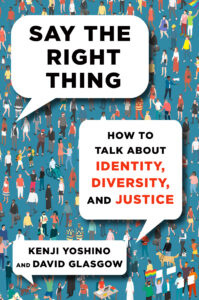

This article is excerpted from Say the Right Thing: How to Talk About Identity, Diversity, and Justice (Atria Books), released on February 7, 2023. Kenji Yoshino and David Glasgow co-founded NYU School of Law’s Meltzer Center for Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging, and have years of experience working with attorneys and other business and cultural leaders on these topics. Their book offers seven research-backed chapters about how to tackle tough topics with neighbors, friends, family members, co-workers, and anyone else you care about. Say the Right Thing will help readers have better conversations that lead to deeper understanding and a fairer society. Learn more about Say the Right Thing.

The children’s book The Magical Yet addresses a child who can’t get the hang of riding a bike and gives up trying. In the book’s illustrations, the child walks along a bike path sulking until she happens upon a glowing pink orb in the bushes known as The Magical Yet. With the Yet’s help, the child learns to persist whenever she makes a mistake, whether it involves playing a musical instrument, learning a language, or riding a skateboard. “No matter how big (or old) you may get,” the book observes, “you’ll never outgrow—you’ll never forget—you can always believe in the magic of Yet.”

The Magical Yet tracks psychologist Carol Dweck’s celebrated argument that people should move from a “fixed mindset” to a “growth mindset.” Individuals with a fixed mindset believe their basic qualities—their intelligence, personality, talents, and moral character—are basically unchangeable. If they’re not good at something, they probably never will be and should give up trying. Individuals with a growth mindset, in contrast, believe they can cultivate their qualities through effort. Across a variety of fields, from relationships to sports to business leadership, Dweck shows that a growth mindset leads to greater success. It prevents people from treating every setback as a verdict on their innate competence and moral worth.

This simple and crucial concept has taken over institutions from corporations to preschools, helping people recover from mistakes and improve their skills. Yet as our NYU colleague and social psychologist Dolly Chugh points out, the concept is glaringly absent from discussions of identity. She explains that people get mired in a fixed mindset on identity issues because the costs of making a mistake seem catastrophic. If you make a mistake when learning a musical instrument, you probably won’t be traumatized. Yet if you make a mistake on an identity issue, you haven’t just made an error—you’ve become a racist, a sexist, or a homophobe. Something you did comes to describe who you are. The perceived threat is so huge it’s no wonder you’re panicked. But that terror means you won’t even try to learn. Imagine if we began a class by saying: “Our one requirement for the semester is that you not make any mistakes.”

As Chugh argues, you won’t make progress until you let go of the fixed-mindset outlook that you’re either a good or bad person and embrace the growth-mindset idea that you’re a “good-ish” person. If you insist you’re a good person, you’re likely to react with overwhelming discomfort when you make a mistake that would reveal your imperfections. If, by contrast, you acknowledge you’re a “good-ish” person who falters like everybody else, you’re less likely to see mistakes as judgments of your character. You can then respond by treating mistakes as opportunities to learn.

Social science research backs up the idea that a fixed mindset derails identity conversations. In a series of experiments, Dweck and her colleagues found that participants with the fixed-mindset view that prejudice was unchangeable were less interested in having cross-racial interactions or learning about bias than people who believed prejudice could change through effort. In one experiment, white participants were put in a room and told they were about to speak with either a Black or white partner. When they expected a Black partner, those with a fixed mindset tended to place their seats farther away from the other person and expressed a desire for shorter interactions than those with a growth mindset. In another experiment, white participants with a fixed mindset made less eye contact, smiled less, and had a faster heart rate in cross-racial interactions. These findings held true even when controlling for the participants’ racial attitudes.

A fixed mindset might also trip you up in a sneakier way. In a separate study, Dweck and her colleague gave college students who did poorly on a test the opportunity to look at the completed tests of other students. Students with a fixed mindset tended to look at the tests of students who performed worse than they did. They didn’t think they could do better, so they settled for easing their discomfort. Students with a growth mindset tended to look at the tests of students who performed better than they did. Because they knew they could improve, they eagerly explored how to do so. A telltale sign of a fixed mindset in identity conversations is the urge to compare yourself to people more biased or gaffe-prone than you. In a growth mindset, you compare yourself to people who display the most inclusive behavior, not the least. Next time you’re at a family dinner and you mess up, watch out for those downward comparisons: “At least I’m not as bad as Aunt Edith!” Try to inspire yourself with role models instead: “What would Aunt Nell say to make this right?”

When you slip into a fixed mindset, we recommend two techniques. The first is to summon The Magical Yet from the bushes and add the word “yet” to the end of negative self-talk. It’s not: “I’m not good at talking about race.” It’s: “I’m not good at talking about race yet.” Educators use this technique a lot. Kenji’s children are not allowed to utter the words “I’m not good at math” at school. Their teachers insist they say: “I’m not good at math yet.”

The second technique is to do a self-comparison. Instead of “My younger colleagues find it so much easier to talk about mental health than I do,” you might say, “I find it easier to talk about mental health than I did a year ago.” We realize this recommendation sits in tension with our other recommendation to engage in upward comparisons to others. But here—and in general—our strategies aren’t mutually exclusive. Take whichever one works for you. If you find it inspiring to compare yourself to role models, do so. If you find it stressful or demoralizing, make self-comparisons instead. Regardless of the technique, the goal is to catch yourself when you’re feeling fatalistic and substitute thinking that’s both more honest and more compassionate.

When she visited our center, civil rights lawyer Chai Feldblum discussed her own struggles with this mindset shift. Feldblum is an iconic figure in American law and a principal author of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Despite her credentials, she told us during an event how she used to dread making mistakes in identity conversations. Whenever she made an error in the past, she said, “all I would do is berate myself.” Yet over a period of years, she learned to focus on growing from the mistake instead of letting it define her.

Feldblum asked us to imagine saying something inadvertently hurtful to a person with a disability. “If you’re not in the disability culture,” she said, “I assure you, you may not know that something you said just did not feel good to that person.” She then shared her recommended form of self-talk in response to that mistake: “Wow, I guess I just wasn’t ever taught that or thought about that.” This shift—from “I’m a terrible human being” to “I just wasn’t ever taught that”—offers you the gift of redemption. Just as importantly, as Feldblum noted, it grants you the opportunity to behave differently next time. If you didn’t learn it before, you can learn it now.