Millions of working Americans (approximately one in five) are subject to noncompetes—that is, legal agreements that restrict employees from activities that increase competition for their employers.[1] In June 2024, just months after the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) voted to implement a nationwide ban on the use of noncompete agreements,[2] the U.S. Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling that overturned Chevron deference—a forty-year-old doctrine that had previously required courts to defer to federal agencies’ interpretations of ambiguous statutes.[3] In August 2024, a district court ruled that the FTC could not implement its proposed ban; the FTC is considering appealing this decision.[4]

Despite the rulings against the FTC’s authority, a key economic question for both sides of the emerging legal dispute concerns the potential consequences of a nationwide noncompete ban. The FTC’s proposed rule comes in the wake of research and speculations regarding the intended and unintended consequences of noncompetes.[5] Some have postulated that a nationwide ban on noncompetes would lead to an increased number of trade secret disputes because, as proponents of noncompetes argue, such agreements are used to safeguard a company’s sensitive information, including trade secrets.[6]

Whether a nationwide ban on noncompetes would have a quantifiable impact on the volume of trade secret cases is ultimately an empirical question—one that the authors of this article examined in a previous publication.[7] In that article, we identified and examined state-level variations in noncompete regulations over time alongside annual federal trade secret caseloads to empirically explore any potential relationship between these two factors. We summarize our main findings here and conclude with some related considerations regarding how companies may approach intellectual property (“IP”) policies in light of the expected regulatory developments in noncompetes.

Impact of Noncompete Regulations on Trade Secret Caseloads

Over the last two decades, states have varied in their approach to whether and how noncompetes are enforced. Using a variety of publicly available sources, we assigned states to one of three categories: (1) states that have already banned noncompetes, (2) states that have introduced various forms of restrictions on the enforcement of noncompetes, and (3) states that enforce noncompetes without restrictions.

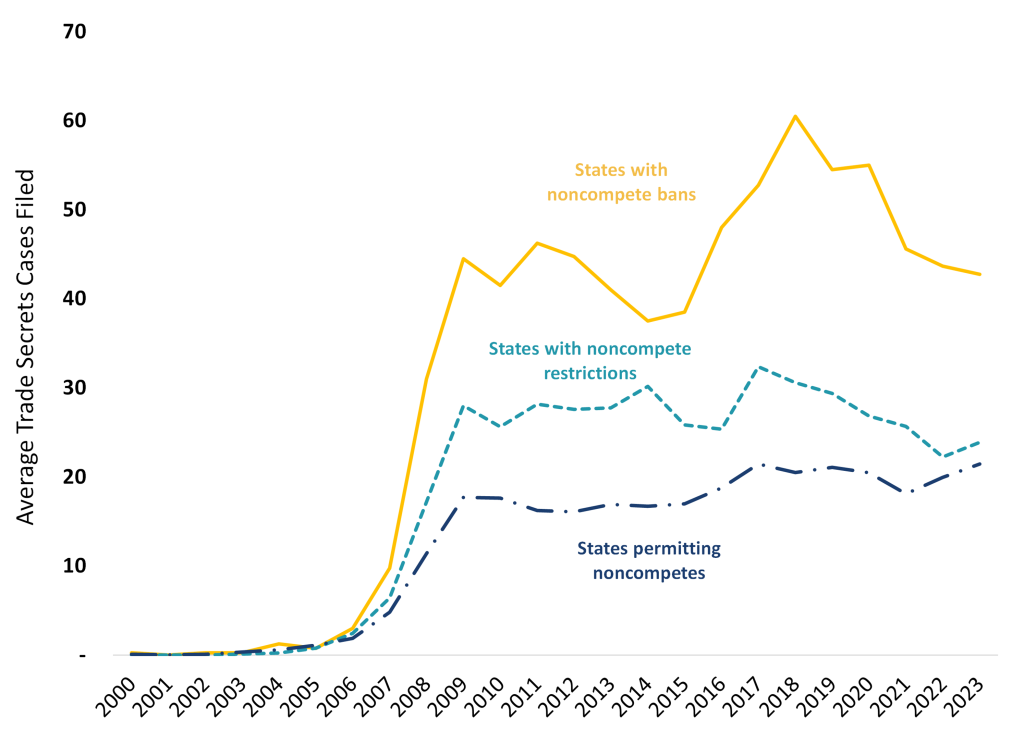

When analyzing the average annual trade secret caseloads across the three categories, we observed that states with a ban on noncompetes experience the highest levels of trade secret cases. Specifically, as presented below in figure 1, beginning around 2006, the average number of trade secret cases was highest among states with a ban on noncompetes (on average, thirty-one annual cases between 2006 and 2023), followed by states that have imposed some form of restriction on noncompete enforcement (on average, eighteen annual cases), and, finally, states that enforce noncompetes without any restrictions (on average, thirteen annual cases). These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that a nationwide ban on noncompetes could lead to more trade secret disputes.

Figure 1. Average number of trade secret cases filed per state, 2000–2023.

Data obtained from Lex Machina, district court cases database. For each year, the total number of cases filed across states in each of the three categories was divided by the number of states in those categories. In the year of transition, each state was assigned to its post-change category.

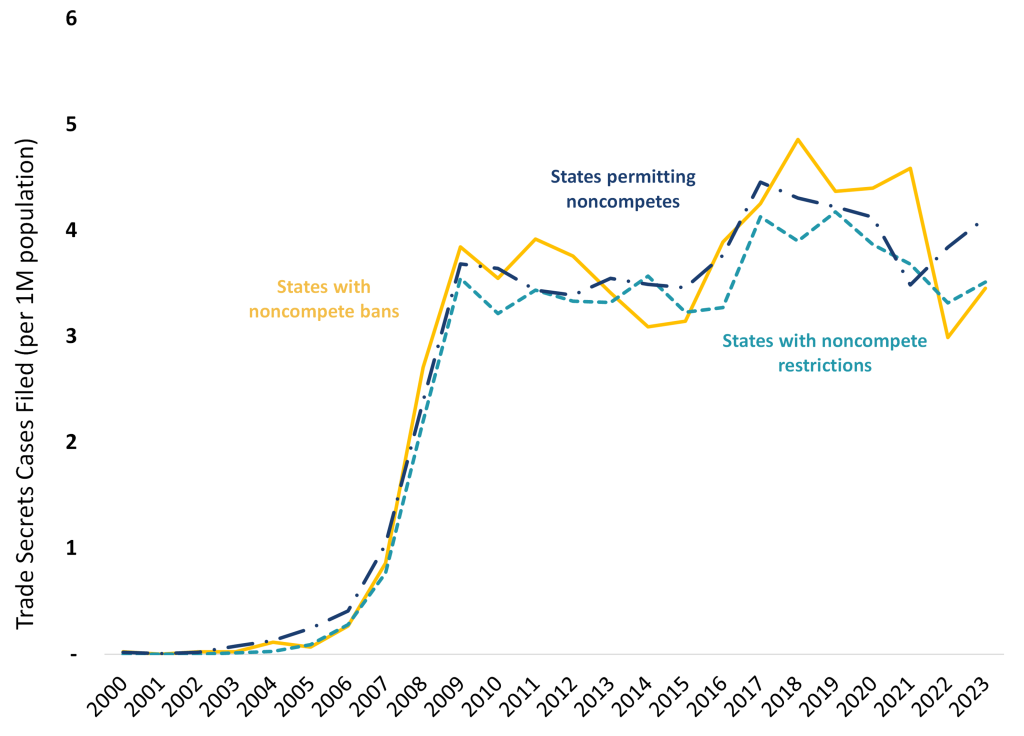

However, subsequent analyses indicated that once we factored in state populations, the results no longer supported the previously implied relationship between noncompetes and trade secrets. In figure 2 below, we reproduce the trends for the three categories of states. This time, instead of plotting the total annual number of trade secret cases divided by the number of states in each category, we plot the volume of trade secret cases per one million residents. The resulting trends across the three categories differ substantially from those in figure 1. Specifically, in figure 2, we do not observe the same ordering of the categories. In fact, the ordering of the categories appears to vary at different points in time. While the trends in figure 1 support the hypothesis that a nationwide ban on noncompetes would increase trade secret cases, the patterns in figure 2, or lack thereof, indicate no evidence of such a relationship. Said differently, observed differences in the volume of trade secret cases across the three categories of states are influenced by state characteristics such as population size rather than solely by their enforcement of noncompetes.

Figure 2. Average number of trade secret cases filed per million population, 2000–2023.

Data on trade secret case counts obtained from Lex Machina, district court cases database. For each year, the total number of cases filed across states in each of the three categories was divided by the total population across those states. In the year of transition, each state was assigned to its post-change category. Population data for the fifty states and Washington, D.C., were sourced from Release Tables: Resident Population by State, Annual, FRED (2000–2023).

When we abstracted from aggregate analyses and instead analyzed individual state-level data, our findings were once again mixed. For some states, including Illinois, Louisiana, and Washington, implementing some form of restriction on the enforcement of noncompetes was followed by a decline in per capita trade secret cases. This implies that doing away with noncompetes may not lead to more trade secret cases. On the other hand, in states like Nevada, Oregon, Utah, and Virginia, implementing some form of restriction on the enforcement of noncompetes was followed by an increase in per capita trade secret cases. The experience in these states implies that doing away with noncompetes may lead to more trade secret cases.

Considerations Regarding How Companies May Approach IP Policy

When the aggregate analysis of the different categories of states and the before-and-after experiences of select individual states are taken together, our findings lead us to conclude that a nationwide ban on noncompetes is unlikely to lead to any immediate surge in trade secret cases. At the same time, however, we recognize that any impact of a nationwide ban on the volume of trade secret cases may not be immediate. Moreover, we do not claim our estimated effects or lack thereof to be causal. We interpret our findings as preliminary and as motivation for state-level analyses that control for additional confounding factors that may impact both the enforcement of noncompetes and the volume of trade secret cases.

Our findings highlight some important considerations regarding how companies may approach their IP policies. When evaluating both existing and new IP strategies, it may be prudent to consider the potential short-term and long-term impacts. This can ensure the retention of valuable IP developed within a company, particularly before any employee departure.

To this end, an initial consideration is determining the most suitable IP protection for the technology being developed. Specifically, companies can prioritize assessing whether patent protection is more appropriate than trade secret protection. A ban on noncompetes could change how companies assess their IP strategy. In particular, when employees and the knowledge they gain from their employers become more portable, it may become harder to keep proprietary, inventive knowledge a secret. If this knowledge offers a competitive advantage, companies may place greater emphasis on securing patent protection. At the same time, as other studies have suggested, trade secrets and patents don’t need to be viewed as mutually exclusive. A viable IP strategy could involve patenting certain aspects of a technology while maintaining trade secret status for others.[8]

Regardless, this highlights an essential task companies should undertake in the light of the potential noncompete ban—revisiting and redefining clear trade secret policies. While trade secret policies may vary across companies due to budget constraints and the nature of the business, having a strong chance of enforcing trade secret protection in litigation requires clear policies. Companies must define what constitutes a trade secret and specify the protective measures in place to maintain its secrecy. This includes establishing protocols for the development, marking, and accessing of the information both physically and electronically. Additionally, in light of the potential ban on noncompetes, trade secret protocols should include oversight of individuals with access to sensitive information. In the absence of noncompete agreements, measures like assignment and confidentiality agreements can help alleviate concerns about the portability of a company’s trade secrets or confidential information.

Noncompetition Agreement, Cornell L. Sch. Legal Info. Inst. (updated July 2023); see also Press Release, Fed. Trade Comm’n, FTC Announces Rule Banning Noncompetes (Apr. 23, 2024). ↑

Press Release, supra note 1; see also Press Release, Fed. Trade Comm’n, FTC Proposes Rule to Ban Noncompete Clauses, Which Hurt Workers and Harm Competition (Jan. 5, 2023). ↑

Chevron Deference, Cornell L. Sch. Legal Info. Inst. (updated July 2024). This shift in power from federal agencies to the judiciary may, among other things, limit the FTC’s ability to enforce a federal ban on noncompetes based on its interpretation of its statutory mandate to protect competition. ↑

See Paul A. Ainsworth & Jonathan Tuminaro, Update: FTC’s Ban on Non-Compete Agreements Set Aside, Sterne Kessler (Aug. 27, 2024). ↑

For example, existing studies on noncompetes have focused on their impact on wages and employee mobility, highlighting differences in enforcement and outcomes in various states or industries. Studies have also explored the broader economic impacts of noncompetes, examining their influence on firm behavior, such as investments in training or research and development, as well as their overall effects on market competition and consumers. Gabriella Monahova & Kate Foreman, A Review of the Economic Evidence on Noncompete Agreements, Competition Pol’y Int’l (May 31, 2023); see also Evan Starr, Noncompete Clauses: A Policymaker’s Guide Through the Key Questions and Evidence, Econ. Innovation Grp. (Oct. 31, 2023). ↑

Rosemary Scott, FTC’s Non-Compete Law Could Propel Rise in Trade Secrets Lawsuits, BioSpace (Feb. 8, 2023); see also Steve Carey, Sarah Hutchins & Tory Summey, FTC’s Noncompete Ban Leaves Room to Prevent Trade Secret Theft, Bloomberg L. (Jan. 24, 2023). ↑

Animesh Giri, April Dang & Marie McKiernan, Noncompetes and Their Potential Impact on Trade Secret Cases, 17 Landslide (Sept./Oct. 2024). ↑

See, e.g., Steven R. Daniels & Sharae’ L. Williams, So You Want to Take a Trade Secret to a Patent Fight? Managing the Conflicts between Patents and Trade Secret Rights, 11 Landslide (Jul./Aug. 2019). ↑