ABSTRACT

According to the Stanford Law School Securities Clearinghouse Class Action website, plaintiffs filed 110 new securities class action cases in the first half of 2022, a slight increase from the prior year period, with both alleged maximum dollar loss and alleged disclosure dollar loss substantially exceeding prior benchmarks. [1] Underwriters are most commonly included among the defendants in cases premised on alleged violations of the Securities Act of 1933 (“Securities Act”)[2] where, among other things, the underwriter’s exercise of professional judgment in making decisions about the scope and character of due diligence, offering document disclosures, red flags, and materiality is often in controversy.[3]

In resolving such cases, courts face the difficult task of balancing investor protection with well-established concepts of fundamental fairness in the application of the law. Often overlooked or underappreciated, however, is the wide range and complexity of operational, financial, legal, and other matters that underwriters and their counsel encounter throughout the due diligence and disclosure process, and the ongoing, organic, and contextually specific professional judgments they must make. These decisions are both profoundly “judgmental in nature” and specific to a particular set of circumstances (context).[4] Moreover, they must be made in “real time” without the benefit of hindsight.

In assessing the reasonableness of an underwriter’s in situ exercise of professional judgment, it is important to understand that the ultimate issue for the court is not the outcome of the judgments, such as whether more or different due diligence could have been conducted or whether more or different disclosures could have been made. Indeed, judgments can and do differ among professionals, even when presented with the same information in the same context, and one can always imagine more or different kinds of due diligence and disclosure. Rather, the fundamental issue for the court is whether the underwriter reasonably believed that the offering documents did not contain material misstatements or omissions and whether that belief was based on reasonable investigation and reliance.[5] Therefore in assessing reasonableness, a court must consider the basis for the professional judgments that were exercised as a part of the broader process.

Essential aspects of this dimension of the reasonableness inquiry are the so-called “standard processes” and “frameworks”[6] (referred to herein as the “Professional Judgment Framework”) the underwriters followed in making their due diligence, disclosure, and materiality decisions.[7] At least one Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) Advisory Committee has stressed the central relevance of Professional Judgment Frameworks in assessing the reasonableness of professional judgments, observing that professional judgment “should be the outcome of a process in which a person or persons with the appropriate level of knowledge, experience, and objectivity forms an opinion based on the relevant facts and circumstances within the context provided…”[8] Moreover, the Committee’s Draft Decision Memo stated that:

Identifying standard processes for making professional judgments and criteria for evaluating those judgments, after the fact, may provide an environment that promotes the use of judgment and encourages consistent evaluation practices among regulators. [9]

This article explores the broad range and inevitable role of professional judgments by underwriters in registered securities offerings and the relevance to judicial determinations of reasonableness of the guidance-based Professional Judgment Framework underwriters customarily follow in arriving at these judgments. The article begins with an overview of the role of underwriters in securities offerings, the reasonableness standard under which they operate, and common sources of underwriter liability and affirmative “reasonableness” defenses. It next explains the concept of “professional judgment” and its exercise by underwriters in registered securities offerings. Finally, it summarizes the guidance-based Professional Judgment Framework commonly employed in the underwriting industry, including both core principles and customary practices.

I. The Role of Underwriters in Registered Securities Offerings

A. Overview

Public offerings must be registered with the SEC in accordance with the provisions of Section 5 of the Securities Act.[10] The registration process involves, among other things, the preparation of written offering documents (a registration statement and prospectus or prospectus supplement, which in some contexts incorporates other information by reference) that contain mandated information regarding the offering, the issuer, and the issuer’s business.[11] Once the registration statement is declared effective by the SEC, the securities may be offered and sold.

When a company decides to raise capital through a registered securities offering, it typically retains one or more underwriters[12] to manage various aspects of the process through which the company’s securities are offered, sold, and distributed to the public. In the most common form of underwriting, a firm commitment,[13] underwriters purchase the securities from the issuer and sell them to investors. Thus, they serve as an intermediary between the issuer and the investing public.[14]

Among other things, underwriters assist in this process by purchasing the securities for resale to the public and, for a period thereafter, maintaining a stable, liquid aftermarket for trading. Supported by counsel, underwriters also conduct due diligence (which involves both investigation and reliance) into a range of operational, financial, legal, and other matters and make ongoing, organic, and contextually specific professional judgments regarding matters such as the scope of that due diligence, the proper range and extent of disclosure, the presence of red flags and how to respond to them, and materiality.

B. Underwriting Syndicates

Most public offerings involve a group of underwriters, commonly referred to collectively as a “syndicate.” Syndicates typically involve one or a small number of lead (or managing) underwriters that assume primary responsibility for the offering and a larger number of participating underwriters that primarily assist with distribution of the securities.[15] The responsibilities of the underwriting syndicate are typically discharged through the lead underwriter(s) and underwriters’ counsel. These responsibilities include advising the issuer regarding the offering, conducting due diligence, reviewing the offering documents in an effort to ensure that they do not contain material misstatements or omissions, assessing the value of securities to be sold, determining the structure and terms of the offering, and creating and managing the distribution of the securities (sometimes referred to as “bookrunning”).[16] As explained below, all of these matters involve the exercise of professional judgment and, as a result, introduce the risk of ex post challenge to the reasonableness of the judgments made.

C. Underwriters as Informational Intermediaries

Securities underwriters are sometimes described as “informational intermediaries” that undertake to reduce “information asymmetries[17] between issuers and investors.”[18] In this capacity, underwriters “help investors [and] share the cost of acquiring, evaluating, and verifying information….”[19] This intermediary status derives from the fact that underwriters conduct due diligence, review offering document disclosures, and perform other activities in connection with the offering which are deemed, at least in part, to be undertaken on behalf of potential investors.

Among other things, underwriters, unlike investors,[20] typically are given access to both public and non-public information throughout the offering process. Thus, the various roles they play and the risks they assume may be seen as fundamental components of a regulatory and industry approach to ameliorating the risk of informational asymmetry.

Some commentators have asserted that underwriters also are “gatekeepers.”[21] Gatekeepers have been defined as “‘intermediaries who provide verification and certification services to investors’ by pledging their professional reputation….”[22] Proponents of the gatekeeper theory typically assert that, not just underwriters but a range of transactional professionals (including attorneys and accountants)[23] should be subject to liability for the wrongdoing of their clients on the implicit assumption that they possess a degree of power over the conduct of their clients. Whether this is in fact true has been the subject of much debate. Indeed, the theory of gatekeeper liability has been described as one of the “many legal strategies for controlling corporate wrongdoing, [and] perhaps the most complex and difficult to justify.”[24]

II. Underwriter Liability and Affirmative Defenses

A. Overview

Underwriters may incur liability under various federal and state securities laws.[25] Among these are the Securities Act, which creates a risk of civil liability if the offering documents for a registered offering contain material misstatements or omissions, and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (“Exchange Act”),[26] which creates a risk of civil or criminal liability for fraudulent conduct. Following is a summary of the common bases of liability for underwriters under each of these Acts and the affirmative “reasonableness” defenses available to them.

B. Section 11 of the Securities Act

Under Section 11 of the Securities Act,[27] any person who purchases a security issued pursuant to public offering documents that contain a material misstatement or omission has a private cause of action. Potential defendants include the issuer, signatories of the registration statement, directors or partners of the issuer, each person named as (or about to become) a director or officer,[28] accountants, engineers, appraisers, or other experts, and underwriters.[29]

Section 11 plaintiffs are not required to prove knowing wrongdoing (scienter),[30] but merely the presence of a material misstatement or omission. Thus, this statute, like Section 12(a)(2) discussed below, focuses only on the presence or absence of material misstatements or omissions in the offering documents.

As explained in more detail below, Section 11 contains two affirmative due diligence defenses[31] that are available to the enumerated defendants including underwriters. The first is a “reasonable investigation” defense for non-expertised material.[32] The second is a “reasonable reliance” defense for expertised material.[33] To meet the burden of proof for the reasonable investigation defense under Section 11, a defendant must establish that it conducted a reasonable investigation and that after such investigation it had reasonable grounds to believe and did believe in the accuracy of the offering documents.[34] To meet the burden of proof for the reasonable reliance defense, a defendant must establish that it had no reasonable ground to believe and did not believe that the expertised portions of the registration statement (such as audited financials) contained material misstatements or omissions.[35]

C. Section 12(a)(2) of the Securities Act

Section 12(a)(2)[36] applies to all sellers[37] of publicly registered securities and prohibits materially false or misleading statements in a prospectus or oral communication related to the sale. Any person who purchases a security issued pursuant to public offering communications that contain such a material misstatement or omission has a private cause of action for rescission or damages.

Like Section 11, a Section 12(a)(2) plaintiff is not required to prove scienter. It only must establish “some causal connection between the alleged communication and the sale, even if not decisive.”[38] Moreover, there is no requirement that the purchaser have relied on the misstatement.[39] Thus, the essential elements of a Section 12(a)(2) violation[40] are: “(1) a direct offer or sale of a security to the plaintiff; (2) in interstate commerce; (3) by means of a prospectus or oral communication; (4) that includes a material misstatement or omission; and (5) an allegation of some loss, where the face of the complaint and judicially noticeable facts do not conclusively negate loss or loss causation.”[41]

For many years, the general understanding was that this statute applied to both public offerings and private placements. However, in 1995, the Supreme Court in Gustafson v. Alloyd Co.[42] held that the statute applies only to public offerings. The basis for excluding private placements appears to derive from two judicial conclusions. The first is that private placements typically involve offerees and purchasers who can fend for themselves and do not need the protections offered by the Securities Act.[43] The second is that private placement plaintiffs have several alternative recourses, including state securities[44] and deceptive practices laws,[45] as well as Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act[46] and Rule 10b-5 promulgated thereunder[47] (the latter two offer remedies for intentional misconduct, which requires a showing of scienter).[48]

Similarly to Section 11, Section 12(a)(2) offers an affirmative “reasonable care” defense. However, unlike Section 11, it contains no reasonable reliance defense, as it does not distinguish expertised and non-expertised material.[49] As discussed below, the SEC[50] and some courts[51] have interpreted “reasonable care” as imposing a different standard than “reasonable investigation.” However, other courts have interpreted the standards as being substantially the same.[52]

D. Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 of the Exchange Act

The Exchange Act[53] prohibits fraudulent conduct in the offer and sale of securities. This prohibition applies both to public offerings and private placements, and courts have interpreted it to give plaintiffs a private cause of action.

The principal anti-fraud provisions of the Exchange Act are Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 promulgated thereunder.[54] Section 10(b) prohibits the use of any manipulative or deceptive practice in connection with securities offerings.[55] Rule 10b-5 makes it unlawful “to make any untrue statement of a material fact or to omit to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statements made, in the light of the circumstances under which they were made, not misleading”[56] in connection with the purchase or sale of securities. These prohibitions apply to oral and written communications as well as manipulative or deceptive practices.

Potential defendants under Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 include every participant in the offering, including the issuer, its officers and directors, participating broker-dealers, underwriters, and accountants.[57]

To prove a violation of Section 10(b) and/or Rule 10b-5, a plaintiff must establish each of the following: (i) the plaintiff was either a purchaser or seller of securities,[58] (ii) the defendant misstated a material fact or failed to state a material fact necessary to make statements that were made, in light of the circumstances under which they were made, not misleading,[59] (iii) the defendant had a duty to disclose the information in question,[60] (iv) the plaintiff relied on the allegedly false or misleading statement in making the investment decision,[61] (v) the violations in question caused the plaintiff to undertake the transaction,[62] and (vi) the damages the plaintiff suffered resulted from the misstatement or omission.[63] Courts also have required the plaintiff to prove that the defendant acted with scienter.[64] For example, in Software Toolworks, the Federal District Court for the Northern District of California stated:

Section 10(b) liability requires a showing of scienter — a mental state embracing intent to deceive, manipulate, or defraud. Scienter may be satisfied either by proof of actual knowledge or by proof of recklessness. The reckless conduct necessary to satisfy the scienter requirement is conduct “involving not merely simple, or inexcusable negligence, but an extreme departure from the standards of ordinary care, and which presents a danger of misleading buyers or sellers that is either known to the defendant or is so obvious that the actor must have been aware of it.” [citations omitted].[65]

E. Affirmative Defenses

1. Reasonable Investigation Defense

The reasonable investigation defense of Section 11 applies only to those portions of the offering documents “not purporting to be made on the authority of an expert” (non-expertised statements)[66] and is only available to signatories of the registration statement, directors, officers, partners of the issuer,[67] experts, and underwriters.[68] Thus, initial steps in a Section 11 analysis include determining whether the material misstatement or omission is contained in expertised or non-expertised material and whether the defendant is an enumerated party.

To meet the burden of proof for the reasonable investigation defense, a defendant must establish that it conducted a reasonable investigation and that after such investigation had:

reasonable grounds to believe and did believe … that the statements therein were true and that there was no omission to state a material fact required to be stated therein or necessary to make the statements therein not misleading.[69]

Thus, the focus of the inquiry with respect to non-expertised material is the reasonableness of the party’s investigation (which also may include elements of reasonable reliance as explained in, among other sources, SEC Rule 176(f)[70]).

2. Reasonable Reliance Defense

The reasonable reliance defense of Section 11 applies only to the portions of the offering documents “purporting to be made on the authority of an expert” (expertised statements)[71] and, like the reasonable investigation defense, is only available to enumerated parties.

Not every statement of an expert constitutes expertised material. Section 11 defines an expert as:

every accountant, engineer, or appraiser, or any person whose profession gives authority to a statement made by him, who has with his consent been named as having prepared or certified any part of the registration statement, or as having prepared or certified any report or valuation which is used in connection with the registration statement, with respect to the statement in such registration statement, report, or valuation, which purports to have been prepared or certified by him.[72]

As Judge Cote explained in WorldCom: “not every opinion qualifies as an expert’s opinion for purposes of the Section 11 reliance defense….”[73] For example, for an accountant’s opinion to qualify as an expert opinion, “it must be reported in the registration statement…, be an audit opinion …, [and] the accountant must consent to inclusion of the audit opinion in the registration statement.”[74]

An expert can assert a due diligence defense with respect to its own expertised material. To do so, the expert must establish either that: (i) it “had, after reasonable investigation, reasonable ground to believe and did believe, at the time such part of the registration statement became effective, that the statements therein were true and that there was no omission to state a material fact required to be stated therein or necessary to make the statements therein not misleading” or (ii) the statement in question did not fairly represent the expert’s actual statement.[75]

Non-issuer, non-experts (such as underwriters) can establish a reasonable reliance defense as to expertised material by demonstrating that either: (i) they had “no reasonable ground to believe and did not believe … that the statements [contained in the expertised portion] were untrue or that [they omitted] a material fact” or (ii) the statement in question did not fairly represent the expert’s actual statement.[76] Thus, the reasonable reliance defense does not require a defendant to conduct a “reasonable investigation” of the expertised material.[77]

3. Reasonable Care Defense

As with Section 11, Section 12(a)(2) offers an affirmative due diligence defense, although it requires “reasonable care” as opposed to a “reasonable investigation” or “reasonable reliance.” Section 12(a)(2) makes no distinction between expertised and non-expertised statements for purposes of the reasonable care defense. Thus, both kinds of material are treated the same, and there is no reasonable reliance defense under this statute (though SEC Rule 176(f) makes clear that reasonable reliance is a part of a reasonable investigation, and presumably reasonable care).[78] Section 12(a)(2) is like Section 11 in that it does not require scienter and the burden of proving the defense rests with the defendant.

4. Implied Affirmative Defense Under the Exchange Act

Unlike Sections 11 and 12(a)(2) of the Securities Act, neither Section 10(b) nor Rule 10b-5 contains an express due diligence defense. Nonetheless, the reasonableness of a defendant’s conduct may influence a court’s views regarding whether scienter exists (a mandatory element of plaintiff’s burden of proof).[79]

Courts have held that establishing an affirmative defense under Sections 11 or 12(a)(2) of the Securities Act negates the existence of scienter under Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act with respect to materially false or misleading statements.[80] For example, the court in Software Toolworks held that “[b]ecause we conclude that the Underwriters acted with due diligence…, we also hold that the Underwriters did not act with scienter regarding those claims.”[81] The judicial reasoning in this regard appears to be that if a defendant reasonably believed the statements made in the offering documents based on its reasonable investigation or reasonable reliance, then that defendant cannot be said to have acted either with scienter or recklessness “with respect to the same assertions under [the Exchange Act].”[82]

III. The Concept of Reasonableness

A. Overview

The standard by which courts assess underwriter due diligence, including the exercise of professional judgment as relates to it, is “reasonableness.” The Securities Act defines reasonableness as what a prudent person (in a similar context) would have done in the management of his or her own property.[83]

While the prudent person has been described as an objective standard,[84] based on a review of case law and relevant literature, the term appears more appropriately understood as a legal fiction reflecting something between the average and ideal persons as determined on a case-by-case basis by the court.[85] As one author put it:

reasonableness is not an empirical or statistical measure of how average members of the public think, feel, or behave…. Rather, reasonableness is a normative measure of ways in which it is right for persons to think, feel, or behave …[86]

Perhaps the best, albeit still opaque, articulation of this concept was offered more than a century ago by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, who stated that legal standards of care should be judged against the conduct of “the ideal average prudent man.”[87]

B. Authoritative and Informative Guidance

As the SEC,[88] the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (“FINRA”) and its predecessor the National Association of Securities Dealers (“NASD”),[89] courts, and other authoritative and informative sources have concluded, reasonableness must rest on its own facts and context.[90] While legislators, regulators, courts, and other authoritative and informative sources have offered guidance regarding the reasonableness of underwriter conduct in certain contexts, no authoritative source has successfully developed a one-size-fits-all checklist of reasonableness appropriate to all contexts (indeed, those undertaking such an effort have consistently determined that such an effort is futile). [91]

Courts assess reasonableness flexibly,[92] applying a “sliding scale”[93] that varies with transactional context,[94] positional context,[95] situational context,[96] and temporal context.[97] Moreover, courts have stressed that the standard is “reasonableness” not “perfection,”[98] with one court even going so far as to note that it would be “truly surprising, given the advantage of hindsight” if one could not find at least some shortcomings in an underwriter’s conduct, but that one’s ability to “poke holes” in that conduct is not dispositive.[99]

Thus, what is reasonable conduct is context specific. The American Bar Association’s Committee on Federal Regulation of Securities Task Force in its “Report of Task Force on Sellers’ Due Diligence and Similar Defenses Under the Federal Securities Laws,” (“ABA Due Diligence Task Force” and “ABA Due Diligence Task Force Report”) for example, stated that: “as a standard of conduct, ‘reasonableness’ is meaningless except in a specific factual context.”[100] Similarly, the NASD has stated that the “type of due diligence investigation that is appropriate will vary….”[101] And, the formal report of the SEC’s Advisory Committee on Corporate Disclosure[102] stressed:

The important point is that each subject person should evaluate the surrounding facts, including the extent of his prior relationship with the registrant, and utilize techniques of investigation appropriate to the circumstances of the offering….

Judicial interpretations of Section 11 have confirmed the principle that what constitutes reasonable investigation and reasonable ground for belief depends upon the circumstances of each registration. The prospect of continued flexible application of that standard by the courts should provide assurance to subject persons that they will not incur unreasonable investigative burdens.[103]

Thus, in assessing reasonableness, including in the exercise of professional judgment, a court must consider the totality of the context.

A further relevant consideration in the reasonableness assessment is industry custom and practice. As Judge Cote stated in Federal Housing Finance Agency v. Nomura: “Industry standards are relevant to the reasonableness inquiry,”[104] especially where the offering involves traditional securities; where the market is competitive; and where the custom and practice are well-established and addressed in pronouncements of government regulators, self-regulatory organizations, and/or practitioner and academic literature.[105] While following the practices common in the industry is not, as Judge Cote explained, dispositive of statutory reasonableness, conduct that conforms to such customary practice may enhance the likelihood that the conduct will be considered reasonable by the court.

In Special Report: Due Diligence Seminars, the NASD described these industry customs and practice as the “standards of the street”:

The standard of reasonableness under Section 11 is, in a sense, a “standard of the street.” In considering whether an underwriter has conducted a reasonable investigation, therefore, one must realize that the standard of reasonableness is not an absolute standard that never changes. Rather, “due diligence” may be construed as a standard that depends to some extent on what constitutes commonly accepted commercial practice. If you can establish that the steps taken meet the standard of the trade as it presently exists, a court should not, in applying the Section 11(c) standard, hold you liable for not being duly diligent despite the fact that you missed something and there was a material omission in the registration statement. What other underwriters are doing and the due diligence standards that are followed on the street are highly relevant in establishing one’s defense. Since the prudent man standard may be construed as a “standard of the street,” one is very reluctant to do anything that varies from street practice because that may weigh heavily in establishing liability. If every other underwriter uses a particular procedure, anyone who varies from that procedure is inviting trouble. It is important, then, to be aware of what other people are doing in similar transactions. This does not mean that that is as far as one should go, but if one does not go as far as the standard of the street, he may be exposing himself to potential liability.[106]

The notion that industry standards are relevant considerations in assessing reasonableness mirrors other areas of the law such as torts where:

[i]n determining whether conduct is negligent, the customs of the community, or of others under like circumstances, are factors to be taken into account, but are not controlling….[107]

Finally, the ABA Due Diligence Task Force summarized the relevance of industry standards in the assessment of reasonableness as follows:

[Reasonableness] requires “exercising [at least]…such attention, perception of the circumstances, memory, knowledge of other pertinent matters, intelligence, and judgment as a reasonable man would have.” In this connection, one should be entitled to cite “the usual and customary conduct of others under similar circumstances…, as an indication of what the community regards as proper” and as “a composite judgment as to the risks of the situation and the precautions required to meet them.”[108]

C. Dangers of Perceptual Biases

In making decisions about complex matters, such as the reasonableness of an underwriter’s professional judgments regarding due diligence, disclosures, red flags, and materiality, humans often use shorthand techniques, referred to as heuristics, to facilitate those decisions. Heuristics are the genesis of perceptual bias, which refers to mental errors caused by these simplified information processing strategies.[109] Such biases include “hindsight bias” (judging a matter, such as an underwriter’s exercise of professional judgment, based on information learned after the fact) and “outcome bias” (judging a matter based on the outcome of the matter to which it related).[110] These biases typically are unconscious and therefore may inadvertently affect judicial or regulatory determinations of reasonableness.[111]

While the temptation to assess an underwriter’s exercise of professional judgment using heuristics including after-acquired information is understandable, succumbing to hindsight, outcome, or other forms of perceptual bias is analytically unsound and intellectually undisciplined. Moreover, it can lead to errant reasoning and faulty conclusions. Indeed, as the Federal District Court for the Northern District of California stated in Software Toolworks:

The Court cannot evaluate an underwriter’s due diligence defense with the benefit of hindsight. The overall investigation performed here was reasonable under the circumstances at the time of the investigation.[112]

Thus, one must avoid judging reasonableness based on perceptual biases given that the inquiry into an underwriter’s conduct, including its due diligence and related exercises of professional judgment, is based on process, not results.[113]

IV. The Concept of Professional Judgment

A. Overview

The term “professional judgment” is not defined in federal securities laws, and the processes and practices associated with the appropriate exercise of an underwriter’s professional judgment in securities offerings is rarely addressed in authoritative and informative literature. Therefore, to understand the concept, one must consider a range of commentary and guidance.

B. Authoritative and Informative Guidance

Professional judgment has been described as “the capacity to logically assess situations or circumstances and to draw sound, objective conclusions that are not influenced by cognitive traps and biases or by emotion.”[114] Some sources have analogized the concept to Aristotle’s definition of wisdom,[115] which as described in The Nicomachean Ethics is “the ability to deliberate well about which courses of action would be good and expedient….”[116] Elaborating on this analogy, these sources note that professional judgment is “neither a matter of simply applying general rules to particular cases nor a matter of mere intuition”[117] but rather “a process of bringing coherence to conflicting values within the framework of general rules and with sensitivity to highly contextualized facts and circumstances.”[118]

The SEC Advisory Committee on Improvements to Financial Reporting (“SEC Financial Reporting Advisory Committee”) addresses professional judgment at some length in its 2008 Draft Decision Memo (“Advisory Committee Draft Memo” or “Draft Memo”).[119] While the Draft Memo focuses primarily on accounting and auditing issues, it also purports to address a broader universe consisting of “gatekeepers, including auditors and underwriters,” and a number of the concepts set forth therein are enlightening.[120]

In the Draft Memo, the Advisory Committee refers to professional judgment as involving “good faith”[121] and “well-reasoned, documented professional judgments,”[122] noting that “those making a judgment should be expected to exercise due care in gathering all of the relevant facts prior to making the judgment.”[123] Moreover, the Advisory Committee explained:

Professional judgment…should be the outcome of a process in which a person or persons with the appropriate level of knowledge, experience, and objectivity forms an opinion based on the relevant facts and circumstances within the context provided….[124]

The Advisory Committee stressed that professional judgments are not statements of fact and that different professionals may make different judgments based on the same information:

Professional judgments could differ between knowledgeable, experienced, and objective persons. Such differences between reasonable professional judgments do not, in themselves, suggest that one judgment is wrong and the other is correct. Therefore, those who evaluate judgments should evaluate the reasonableness of the judgment, and should not base their evaluation on whether the judgment is different from the opinion that would have been reached by the evaluator.[125]

As explained above, underwriters, of necessity, make many ongoing professional judgments regarding, among others, the scope and character of the due diligence to be conducted, the implications of that due diligence for the disclosures in the offering documents, red flags, and materiality. All of these professional judgments may be, and often are, challenged, through the lens of hindsight, in post-closing litigation and enforcement actions. However, as explained above and as the Advisory Committee noted, “the use of hindsight to evaluate judgment…is not appropriate.”[126]

C. Relevance of a Professional Judgment Framework

According to the Advisory Committee Draft Memo, professional judgments should be executed pursuant to “standard processes” involving a “framework [that] may provide investors with greater comfort that there is an acceptable rigor that companies follow in exercising reasonable professional judgment.”[127] The SEC Financial Reporting Advisory Committee explained its rationale for this conclusion as follows:

Identifying standard processes for making professional judgments and criteria for evaluating those judgments, after the fact, may provide an environment that promotes the use of judgment and encourages consistent evaluation practices among regulators.[128]

In the case of underwriters, a guidance-based “framework” incorporating “standard processes” for the exercise of professional judgment has been commonly employed in the industry for many years. That framework and those standard processes are based on more than six decades of guidance from the SEC[129] and its Corporate Disclosure Advisory Committee,[130] FINRA (and its predecessor the NASD),[131] the ABA Due Diligence Task Force,[132] the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (“SIFMA”),[133] and practitioner and scholarly literature.[134] The core principles and customary practices associated with this Professional Judgment Framework are addressed in the next sections of this article.

V. The Inevitability of Professional Judgments by Underwriters

A. Overview

As explained earlier, underwriters (and, indeed, other transactional professionals) inevitably are required to make many judgments throughout the securities offering process. As the SEC Corporate Disclosure Advisory Committee explained:

…[the] value of judgment should not be overlooked. Facts are not pristine, clearly defined, unequivocal, or susceptible of a single interpretation. As the complexities of industrial enterprise have grown the opportunities for diverse judgments concerning the importance of individual facts or complex configurations of facts have multiplied….[135]

The factors to be considered in making such judgments can be extensive and, as explained above, are unique to the context presented. Moreover, the exercise of professional judgment often involves significant and varying levels of uncertainty. Thus there is no precise formula or “preflight checklist” regarding how to make an informed professional judgment. Each individual or team must decide, on a case-by-case basis, what factors to consider, how those factors should be analyzed and assessed, and then, applying their knowledge and expertise, reach their own conclusions. In the context of a registered offering of securities, these judgments typically involve, among others, the scope and character of due diligence, the nature and extent of disclosures, red flags, and materiality.

B. Materiality

Nearly every aspect of an underwriter’s work for a public offering of securities involves making professional judgments about what information is material. Judicial pronouncements regarding materiality have arisen primarily in the context of offering document disclosures; however, much of the judicial analysis and discussion is relevant to a range of materiality judgments.

Among the concepts applicable to professional judgments regarding materiality are:

- Materiality is “inherently fact-specific.”[136]

- Materiality should be evaluated with reference to a “reasonable investor” standard involving a multi-faceted, fact-specific inquiry incorporating both qualitative and quantitative factors.[137]

- A matter is material “if there is a substantial likelihood that a reasonable shareholder would consider it important” and, as relates to disclosure, if the matter would have “significantly altered the ‘total mix’ of information available.”[138]

Regarding offering document disclosures, courts have held that the central issue is “whether representations, viewed as a whole, would have misled a reasonable investor.”[139] However, courts also have cautioned that:

- Some “misrepresentations in an offering are immaterial as a matter of law, because it cannot be said that any reasonable investor could consider them important in light of adequate cautionary language set out in the same offering.”[140]

- “Some information is of such dubious significance that insistence on its disclosure may accomplish more harm than good.”[141]

Materiality judgments by underwriters are unavoidable in the context of a securities offering. They include, among others, defining what information is material for purposes of tailoring the scope and character of due diligence, assessing the proper nature and extent of disclosures in the offering documents, and deciding when something is a red flag and, if so, how to respond to it. Each of these matters is addressed separately below.

C. Due Diligence

Understandably, each issuer and offering presents an extensive array of complex operational, financial, regulatory, and other matters. As a result, each securities offering is unique and presents different transactional, situational, positional, and temporal contexts.[142]

As a result, no underwriter due diligence undertaking, no matter how carefully structured and performed, can ever probe the depths of every conceivable matter, nor can it be assured of revealing every piece of information that may later be cast as material. Indeed, such a standard would be profoundly unfair and constitute a burden no underwriter, no matter how dedicated or competent, could bear. Rather, the underwriter must exercise professional judgment in defining the scope and character of its due diligence. Therefore, at the beginning of the securities offering process (and potentially at various points along the journey), underwriters and their counsel endeavor to determine what issues are likely to be material to a prudent person and focus their due diligence on those matters. This process, which of necessity involves professional judgment, is referred to as “tailoring.”

D. Disclosures

Just as an underwriter must make professional judgments regarding the tailoring decisions undertaken regarding the scope and character of due diligence, so too it must make professional judgments regarding the appropriate nature and extent of the disclosures to be contained in the offering documents. As with all exercise of professional judgment, this can be a challenging endeavor especially since underwriters are not expected to possess the intimate knowledge of corporate affairs of insiders and typically have more limited access to information.[143] As the SEC Corporate Disclosure Advisory Committee explained:

…[N]o organization, even an “information disseminator,” can or expects to collect all the information desired or even required for investment decision-making. Even the most broadly based “information disseminator” necessarily makes decisions as to which specific items of information will be collected, processed and communicated to users. This is not an objective process; it is judgmental and evaluative.[144] …

Ranking or selection is required essentially because all disseminators obtain or receive far more information than they can communicate to users. Since even highly specialized disseminators operate within a limited space, judgments as to what information shall be communicated are necessary.[145]

Moreover, the Committee explained that the materiality of a given disclosure is “judgmental in nature”:

Although the Committee believes that ideally it would be desirable to have absolute certainty in the application of the materiality concept, it is its view that such a goal is illusory and unrealistic. The materiality concept is judgmental in nature and it is not possible to translate this into a numerical formula. The Committee’s advice to the Commission is to avoid this quest for certainty and to continue consideration of materiality on a case-by-case basis as disclosure problems are identified.[146]

As a result of these and other considerations, an underwriter’s professional judgments regarding disclosures “will necessarily encompass the selection of facts to be disclosed or withheld, the timing of disclosures, [and] the wording of releases and documents…”[147]

E. Red Flags

A common allegation in securities offering lawsuits against underwriters is that they encountered so-called red flags and failed to make appropriate professional judgments related to them. Under authoritative and informative guidance, red flags require further action in accordance with the contextually applied prudent person standard.[148]

As an initial matter, it is important to understand that there is no one-size-fits-all definition of a “red flag” that is appropriate in all contexts. Indeed, as Judge Cote stated in her seminal WorldCom ruling, what constitutes a red flag “depends on the facts and context of a particular case.”[149] For example, Judge Cote defined a red flag in the context of a securities offering as “any information that would cause a ‘prudent man in the management of his own property’ to question the accuracy of the registration statement.”[150] Moreover, she cautioned that one must take care to distinguish a red flag from an “ordinary business event,”[151] recognizing that what might be unusual in one context may be a customary attribute of an issuer’s business or industry in another context.

It is important to understand that the mere presence of a red flag has no bearing on the reasonableness of an underwriter’s conduct including its exercise of professional judgment. That matter is determined based on the underwriter’s awareness of the red flag, its response to it, and whether the red flag negated the underwriter’s belief that the offering documents did not contain material misstatements or omissions. Thus, even if a red flag is found to exist, an underwriter may still have acted reasonably provided the matter was adequately addressed such as through further investigation, disclosure in the offering documents, or other means the court deems reasonable.

VI. Underwriting Industry’s Guidance-Based Professional Judgment Framework

A. Overview

Because all professional judgments involve a degree of subjectivity, a properly constructed and employed Professional Judgment Framework (which commonly includes both core principles and customary practices) can assist courts, regulators, and others assessing the reasonableness of the exercise of professional judgments.

As the SEC Financial Reporting Advisory Committee has explained, establishing and following a Professional Judgment Framework is important to sound decision-making.[152] Moreover, other organizations, such those providing guidance to financial reporting decision makers, concur:

The professional judgment framework identifies core principles and provides a structured process to guide decision makers through how to make, assess and document significant judgements….[153]

For many years, underwriters, like others including accounting professionals, have commonly employed a Professional Judgment Framework involving both core principles and customary practices. The following portions of this article explain both.

B. Core Principles

1. The Professional Judgment Process Relies on Issuers to Provide Relevant and Accurate Information

In conducting due diligence, assessing disclosures and red flags, and making materiality judgments about both, underwriters rely on issuers to provide relevant and accurate information. Judicial decisions and regulatory guidance acknowledge this, noting among other things that if information was deliberately concealed from the underwriters, their exercise of professional judgment is likely to be impaired.[154] Thus, a core principle of the underwriting industry’s Professional Judgment Framework is that issuers, and indeed others involved in the offering process, will fulfill their own obligations to disclose relevant and accurate information to the underwriters and will understand that such information will be used by the underwriters and their counsel to make professional judgments regarding a range of matters throughout the process including as relates to due diligence and disclosures.

2. The Professional Judgment Process Is Disclosure Focused

The securities offering regulation regime under which underwriters in the United States operate is disclosure focused, not merit-focused.[155] Therefore, a significant focus of the underwriter’s activities in a public offering involve efforts designed to help ensure that the offering documents do not contain material misstatements or omissions.

It is important to understand, however, that whether offering documents contain material misstatements or omissions is a separate and distinct question from whether an underwriter’s conduct, including its professional judgments regarding due diligence, disclosures, red flags, and materiality, is reasonable.[156]

For example, in its Conference Report related to the Securities Act, the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce stated that liability is different for underwriters than for issuers:

[T]o require them [persons other than the issuer] to guarantee the absolute accuracy of every statement that they are called upon to make would be to gain nothing in the way of an effective remedy and to fall afoul of the President’s injunction that the protection of the public should be achieved with the least possible interference to honest business.[157]

Moreover, the SEC has acknowledged and confirmed its agreement with this Congressional intent:

Congress’ goal was not to have underwriters act as insurers of an issuer’s securities. Accordingly, Congress provided underwriters and others with a ‘due diligence’ defense. An underwriter is not liable under Section 11 [of the Securities Act] for the non-expertised portions of the registration statement if, after reasonable investigation, it had reasonable grounds to believe (and did believe) that the statements in the registration statement “were true and that there was no omission to state a material fact required to be stated therein or necessary to make the statements therein not misleading….”[158]

Thus, both authoritative and informative sources make clear that underwriters are not guarantors of statements made in offering documents, and that Congress never intended to impose guarantor status on them. Instead, their obligation is to form a reasonable belief, based on reasonable investigation and reliance, that the offering documents did not contain material misstatements or omissions.[159]

3. The Professional Judgment Process Includes Both Investigation and Reliance

An underwriter’s professional judgments in a securities offering derive from and are based on both its independent investigation (both current and cumulative, as explained below) and its reliance on persons whose duties place them in a position to know about the matter in question. Reliance may either be on experts regarding expertised material (such as an issuer’s audited financial statements) or on non-experts regarding non-expertised material (such as legal opinions,[160] comfort letters and responses to circle-up requests,[161] issuer representations and warranties, and management certifications[162]). Underwriters generally may rely on expertised material without the necessity of an independent investigation[163] and on the non-expertised material as part of a reasonable investigation.

Under subsection (f) of SEC Rule 176 entitled “Circumstances Affecting the Determination of What Constitutes Reasonable Investigation and Reasonable Grounds for Belief Under Section 11 of the Securities Act,” underwriters may appropriately rely on persons whose duties place them in a position to know about the matter in question:

In determining whether or not the conduct of a person constitutes a reasonable investigation or a reasonable ground for belief meeting the standard set forth in section 11(c), relevant circumstances include, with respect to a person other than the issuer…(f) Reasonable reliance on officers, employees, and others whose duties should have given them knowledge of the particular facts (in the light of the functions and responsibilities of the particular person with respect to the issuer and the filing).[164]

Thus, the SEC has made clear that reliance is not limited to expertised material but is also a relevant part of a reasonable investigation (and by extension the exercise of reasonable care) related to non-expertised material. Similarly, courts have expressed the view that an underwriter can discharge its due diligence obligation with respect to non-expertised material by relying (as part of its reasonable investigation or exercise of reasonable care) on such persons.

In sum, reasonable reliance on the statements of and information provided by persons “whose duties place them in a position to know,” whether experts or otherwise, is an element of reasonable investigation and reasonable care.[165] Indeed, reasonable reliance on others—including the issuer’s management team, attorneys, and independent accounting professionals—has been a component of guidance-based industry custom and practice for decades that facilitates the orderly and efficient progress of securities offerings. Moreover, it recognizes the reality that no underwriter, however capable or dedicated, can independently investigate every aspect of an issuer, its business operations and financials, or the offering.

4. The Professional Judgment Process Strikes a Balance Between Reliance and Verification

While a number of judicial decisions have addressed the concept of verification of information relied upon, Rule 176(f) contains no express requirement that the information relied on thereunder be verified by an underwriter. Nonetheless, an underwriter’s alleged failure to verify such information is often in controversy in securities offering litigation. Therefore, core principles of the underwriting industry’s Professional Judgment Framework include a recognition that verification may be appropriate in some (but not necessarily all) contexts. As Judge McLean explained in one of the earliest underwriter defendant cases, Escott v. BarChris:

It is impossible to lay down a rigid rule suitable for every case defining the extent to which such verification must go. It is a question of degree, a matter of judgment in each case.[166]

In considering the relationship between reliance and verification, Professor Leahy, a former capital markets practitioner at a global law firm and now a tenured professor, has observed that a prudent person (the benchmark for underwriter conduct) does not always consider it necessary to verify all information it receives:

[m]ost likely, a prudent investor would not bother to perform her own investigation of the issuer’s statements if (1) there were good, objective reasons for the investor to trust the issuer’s statements in question; or (2) the issuer had effectively warranted the statements. Under such circumstances, a prudent investor probably would either simply (1) make sure that the issuer was objectively trustworthy or (2) independently verify whether the issuer could likely make good on its express warranty.[167]

In addressing the passages of BarChris and Feit commonly cited as support for the proposition that an underwriter’s trust in management is irrelevant in assessing the reasonableness of its reliance, Professor Leahy asked: “does a prudent person never trust?” After examining the rulings in BarChris and Feit, he concluded that prudent persons do indeed trust, noting that:

On its face, BarChris explicitly rejects trust. Underwriters performing due diligence must not trust the issuer’s statements, the decision commands, because ‘a prudent [person] … would not’ do so…. In fact, Judge McLean’s inflexible edict does not hold up to scrutiny for several reasons. First, the BarChris court cited no authority for the proposition that a prudent person never trusts. And there is no legal precedent for this proposition, either in securities laws or the analogous context of the law of trusts. Nor is the author aware of any empirical data to support the assertion that trust in management is an anathema to the prudent investor. [Indeed] Judge McLean’s commandment to [defendants] is not to ‘never trust management’—which defies logic—but rather, to ‘never trust management unless there is good, objective reason to do so.’[168]

Finally, it is important to note that when an underwriter deems verification judgmentally appropriate, it can be accomplished in a variety of ways and on the basis of a range of sources from both inside and outside the issuer. Several courts, for example, have found “internal” verification activities to be compelling. For example, in Weinberger v. Jackson and Software Toolworks, the respective courts noted favorably several verification activities undertaken by the underwriters that did not involve sources of information outside the issuer (thus, the verification was “internal”). These included meetings with management and a review of company provided documents.[169] Courts also have found favorable indications of reasonableness in verification activities that were “outside” the issuer and its management, such as interviews with customers, lenders, manufacturers, and distributors.[170]

In sum, the industry’s Professional Judgment Framework recognizes that verification is not required in all contexts. Whether or precisely when it may be required (and the exact nature of the kinds of verification activities that may be appropriate) is ultimately a matter of professional judgment.

5. The Professional Judgment Process Involves Both Current and Cumulative Due Diligence

An underwriter’s exercise of professional judgment in a securities offering is typically based in significant part on it experience and the results of its due diligence. In this regard, it is important to understand that underwriter due diligence (which as explained above involves both independent investigation and reliance) typically has two temporal parts—current due diligence and cumulative due diligence. Current due diligence is conducted at or around the time of the offering. Cumulative due diligence is conducted over a more extended timeframe (often in less formal or regimented ways) prior to the time of the offering. Cumulative due diligence is especially relevant in the context of an expedited offering such as a shelf takedown, but it is also often present in other contexts such as initial public offerings.

Cumulative due diligence can derive from a variety of sources, including prior transactions and business dealings between the issuer and one or more of the underwriters or their affiliates (such as lending transactions or advisory work) and ongoing engagement in the issuer’s industry (for example, through analyst coverage and/or bringing an analyst over the wall[171] to assist the underwriting team in its due diligence). This is why the SEC has stated that an assessment of an underwriter’s due diligence should consider preexisting familiarity with the issuer and the industry, which the SEC has described as a “reservoir of knowledge.”[172] This reservoir means that an underwriter’s due diligence for a given offering, and the professional judgments it makes in part on the basis thereof, does not start from a blank slate but rather builds on the reservoir of knowledge associated with these kinds of activities.

C. Customary Practices

1. Overview

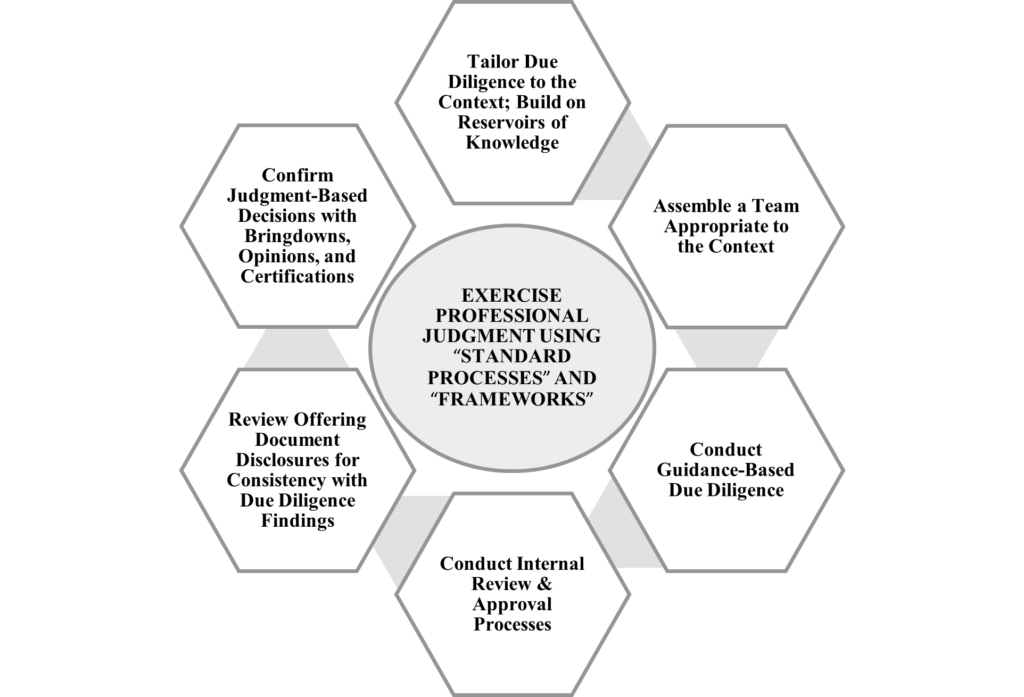

In addition to the core principles discussed above, the underwriting industry’s customary Professional Judgment Framework includes several specific practices that, like the core principles, are based on many decades of authoritative and informative guidance. These practices are summarized in the following schematic:

2. Underwriters Build on “Reservoirs of Knowledge”

As explained above, underwriter due diligence (which informs the exercise of professional judgment) may be both current and cumulative in nature, with current due diligence building on “reservoirs of knowledge” derived from cumulative due diligence conducted over time. Consistent with SEC guidance,[173] where such a reservoir of knowledge is present, underwriters build on that foundation in defining the scope and character of their current due diligence. The practice of building on reservoirs of knowledge (including any such reservoir possessed by counsel) facilitates the making of informed professional judgments.

3. Underwriters Assemble a Team Appropriate to the Context

Professional judgments may be made independently by an individual or collectively by a group of individuals on the underwriter’s team. Accordingly, a customary practice incorporated into the industry’s Professional Judgment Framework is staffing the underwriting team with persons whose experience and expertise make them suited to the context.[174] Such staffing typically involves both more experienced senior personnel and more junior or less experienced personnel working under their supervision. This team is supported by legal counsel that typically conducts legal, regulatory, and documentary due diligence and assists with the process of drafting and/or reviewing the disclosures contained in the offering documents.[175] The practice of assembling an appropriate team for the offering facilitates the making of informed professional judgments.

4. Underwriters Conduct Review and Approval Processes

Serving as an underwriter involves many financial, legal, and reputational risks. Therefore, a customary practice under the industry’s Professional Judgment Framework typically includes an internal review and approval process. This process commonly requires a broader cross-section of the investment bank (typically including one or more persons who are less engaged in the “shovel-and-spade” work of the transaction-specific work) to reach a decision regarding an underwriter’s participation in an offering.[176]

Such review and approval processes commonly involve preparation of memoranda or other documentation regarding the issuer, offering, due diligence conducted to a specified point in time, and other matters. Such memoranda or documentation typically are presented to one or more internal committees whose approval is required to proceed with the transaction.[177] The practice of conducting internal review and approval processes provides an additional level of checks and balances regarding the exercise of professional judgments.

5. Underwriters Conduct an Independent Investigation

Another customary practice under the industry’s Professional Judgment Framework (and regulatory mandate) is the performance of due diligence by the underwriting team and underwriters’ counsel. While the precise scope and nature of the due diligence conducted is context specific, it typically involves a range of formal activities such as meetings; conference calls; due diligence sessions with, among others, attorneys, accountants, members of the issuer’s management and/or staff (internal sources), and, depending on the context, third parties (external sources); offering document reviews; and bringdown sessions. It also typically involves less formal activities such as email communications, telephone calls, texts, and informal discussions. Both formal and informal due diligence processes may occur in person or virtually.

Moreover, as explained above, an underwriters’ due diligence process may begin with a consideration of information learned through prior cumulative due diligence related to the issuer and/or the industry. With the goal of reasonableness in mind, the proper scope and character of due diligence is determined with reference to the context and in the exercise of the underwriter’s professional judgment.

6. Underwriters and Counsel Review Offering Documents

As explained earlier, the securities regulatory regime in the United States is focused on disclosure. Therefore, among the customary practices included in the underwriting industry’s Professional Judgment Framework is a focus on the disclosures contained in the offering documents.

Typically, underwriters, in collaboration with underwriters’ counsel, review offering document disclosures to make professional judgments regarding their consistency with the results of due diligence and to support a belief that the offering documents do not contain material misstatements or omissions (the issuer’s independent auditor and both issuer’s and underwriters’ counsel also review them for a similar purpose and make representations to the underwriters in support of their due diligence).

Because the offering document drafting and review process tends to focus on the offering documents in a line-by-line, word-by-word fashion, these sessions are part of the information disclosure and verification process and, therefore, a part of the due diligence process that supports the exercise of professional judgment.[178] In addition, drafting sessions allow the participants to make collective judgments regarding disclosures based on information learned in the course of due diligence, thereby enhancing the quality of the professional judgments made regarding the sufficiency of the disclosures.

7. Underwriters Conduct Bringdown Due Diligence

Another customary practice under the industry’s Professional Judgment Framework is the conduct of bringdown due diligence which occurs at various latter stages of the offering process such as pre-pricing and pre-closing.[179]

This bringdown process is designed to give underwriters and underwriters’ counsel a final formal opportunity to question the issuer and others directly about various matters, including whether there have been any significant changes that need to be reflected in the offering documents and, if not, to confirm the continuing material accuracy and completeness of the statements made therein. They also give issuers and others an opportunity to apprise the underwriters of any recent material developments. Due to the late-in-process timing of the bringdown process, it is not intended to repeat steps already taken by the underwriters in prior stages, such as earlier due diligence calls or meetings, but is intended as a final check on a range of matters relevant to the exercise of professional judgment. The practice of conducting bringdown due diligence sessions facilitates the making of informed professional judgments.

8. Underwriters Support Their Professional Judgments with, Among Other Things, Opinions and Representations of Counsel, Issuer Representations and Warranties, Management Certifications, and Auditor Comfort Letters

A final customary practice under the industry’s Professional Judgment Framework is for underwriters to support their professional judgments with certifications and assurances from others whose duties place them in a position to know about the matters in question (as contemplated by SEC Rule 176(f) discussed above). These commonly include legal opinions, representation letters, representations and certifications of the issuer and senior management, and comfort letters and circle-ups from the issuer’s independent auditor.

The legal opinions typically address a range of legal and regulatory matters, such as due organization and compliance with legal or regulatory requirements. The representation letters typically address the adequacy of the offering documents disclosures[180] and take the form of so-called negative assurances by counsel that nothing has come to its attention that caused it to believe that the offering documents contain any untrue statements of material fact or omit to state a material fact necessary to make the statements therein not misleading in light of all the circumstances. To give these opinions and representation letters, law firms typically conduct their own independent investigation, including a review of the offering documents and the completion of an internal review and approval process.[181]

Similarly, underwriters support their professional judgments with representations and certifications from the issuer and its management who, like the attorneys noted above and the auditors below, are persons “whose duties should have given them knowledge of the particular facts.”[182] Among these are confirmations that the offering documents do not contain material misstatements or omissions. Because underwriters are not operators of the issuer’s business and do not take part in its management, these assurances provide additional support for the underwriters’ belief that the offering documents do not contain material misstatements or omissions. By requiring the issuer (typically in representations and warranties in the underwriting agreement) and individual officers (typically in certificates issued pursuant to the closing conditions of the underwriting agreement) to certify matters including the lack of material misstatements or omissions in the offering documents, the industry’s Professional Judgment Framework imposes an enhanced level of formality and weight on the issuers and officers that further enhances the basis for their professional judgments.

A final example of reliance-based support for the underwriter’s professional judgments is the receipt of comfort letters from the issuer’s independent auditor.[183] These letters usually incorporate responses to circle-up requests. Circle-ups refer to the underwriters’ or their counsel’s line-by-line review of the offering materials and the “circling” of financial figures and similar statements made in them regarding which the underwriters seek confirmation and/or support from the issuer’s independent auditor and a description of the basis therefore.[184] Like legal opinions, negative assurance letters, issuer representations and warranties, and management certifications, such comfort letters and circle-ups impose an enhanced level of formality and weight on the auditor and further enhance the basis for the underwriters’ professional judgments.

VII. Conclusion

Throughout the securities offering process, underwriters are required to make many ongoing, organic, and contextually specific professional judgments. Most notable among these are judgments regarding the scope and character of due diligence, the nature and extent of disclosures, red flags, and materiality. These decisions are both profoundly judgmental in nature and specific to a particular set of circumstances. Moreover, they must be made in real time without the benefit of hindsight.

The reasonableness of these professional judgments is commonly at issue in securities litigation involving underwriter defendants. In resolving such cases, courts face the difficult task of assessing reasonableness in a way that balances investor protection with fundamental fairness in the application of the law. As explained in this article, essential aspects of the reasonableness inquiry regarding the exercise of professional judgment by underwriters are the “standard processes” and “framework” pursuant to which such judgments are made. Developing a better understanding of and appreciation for the underwriting industry’s guidance-based processes and framework pursuant to which such judgments are made will assist courts in striking an appropriate balance between these two legitimate, indeed foundational, considerations.

Mr. Lawrence is an adjunct professor of advanced due diligence studies at the Dedman School of Law, Southern Methodist University, and a prominent transactional scholar and practitioner. His published work has been cited authoritatively by the Federal District Court for the Southern District of New York, in filings before the Supreme Court of the United States, and in academic and practitioner publications, and he has advised the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Among others, he is the author of the two-volume treatise Due Diligence in Business Transactions, a leading work in the field for more than twenty-five years, and the graduate texts Due Diligence: Investigation, Reliance & Verification—Cases, Guidance & Contexts; Due Diligence: Law, Standards and Practice; Due Diligence, a Scholarly Study; and Due Diligence in Negotiated Transactions: Applied Skills & Exercises. He holds a J.D. degree from Vanderbilt Law School and has been admitted to the bars of New York, the District of Columbia, and Texas. Portions of this article, adapted to the topic addressed, draw in part from selected material included in Mr. Lawrence’s extensive prior publications including the texts noted above and In Search of Reasonableness: Director and Underwriter Due Diligence in Securities Offerings, 47 Sec. Reg. L.J. 189 (Fall 2019).

https://securities.stanford.edu/research-reports/1996-2022/Securities-Class-Action-Filings-2022-Midyear-Assessment.pdf (last visited Oct. 23, 2022). ↑

15 U.S.C. §§ 77a et seq. ↑

See, e.g., Roger J. Dennis, Materiality, and the Efficient Capital Market Model: A Recipe for the Total Mix, 25 WM & MARY L. REV. 373 (1983). ↑

1 HOUSE COMM. ON INTERSTATE AND FOREIGN COMMERCE REPORT OF THE ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON CORPORATE DISCLOSURE TO THE SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION (November 3, 1977) (“SEC Corporate Disclosure Advisory Committee Report”) at 327 (“Although the Committee believes that ideally it would be desirable to have absolute certainty in the application of the materiality concept, it is its view that such a goal is illusory and unrealistic. The materiality concept is judgmental in nature and it is not possible to translate this into a numerical formula. The Committee’s advice to the Commission is to avoid this quest for certainty and to continue consideration of materiality on a case-by-case basis as disclosure problems are identified.”). ↑

15 U.S.C. § 77k(a). ↑

DRAFT DECISION MEMO OF THE SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON IMPROVEMENTS TO FINANCIAL REPORTING, American Law Institute – American Bar Association Continuing Legal Education ALI-ABA Course of Study, February 21–22, 2008, Corporate Governance: The Changing Environment (ALI 2008) (“SEC Financial Reporting Advisory Committee Draft Memo”). ↑

See generally id. ↑

Id. at *72. The Committee’s focus was the exercise of professional judgment in the context of financial reporting, and therefore a number of its observations and recommendations were made with reference to that context. However, the general principles articulated by the Committee, especially as they relate to the importance of “standard processes” and “frameworks” in the exercise of professional judgment, are relevant in other contexts, as the Draft Memo noted. See, e.g., id. at *53. ↑

Id. at *66–67. ↑

15 U.S.C. § 77e. ↑

See, e.g., Milton Cohen, “Truth in Securities” Revisited, 79 HARV. L. REV. 1340, 1344–45 (1966). ↑

The Securities Act defines an underwriter as: “…any person who has purchased from an issuer with a view to, or offers or sells for an issuer in connection with, the distribution of any security, or participates or has a direct or indirect participation in any such undertaking, or participates or has a participation in the direct or indirect underwriting of any such undertaking….” 15 U.S.C. § 77b(a)(11). ↑

In a firm commitment underwriting, the underwriters are obligated to purchase the securities from the issuer and thereby assume the risk of selling those securities to investors. See Edward F. Greene, Determining the Responsibilities of Underwriters Distributing Securities Within an Integrated Disclosure System, 56 NOTRE DAME L. REV. 755, 763 (1981). ↑

In re WorldCom, Inc. Sec. Litig., 346 F. Supp. 2d 628, 662 (S.D.N.Y. 2004). ↑

See generally William K. Sjostrom, Jr., The Due Diligence Defense Under Section 11 of the Securities Act of 1933, 44 BRANDEIS L.J. 549, 584–85 (Spring 2006); Shane Corwin and Paul Schutz, The Role of IPO Underwriting Syndicates: Pricing, Information Production and Underwriter Competition, 60 J. FIN. 443, 445–450 (2005). ↑

See generally Noam Sher, Negligence Versus Strict Liability: The Case of Underwriter Liability in IPO’s, 4 DEPAUL BUS. & COMM. L.J. 451 (2006). ↑

Information asymmetry refers to the notion that one party to a transaction may have more or superior information compared to another. See generally Nathalie Dierkens, Information Asymmetry and Equity Issues, J. FINANCIAL QUANT. ANAL., vol. 26, no. 2 (1991). The securities offering due diligence process, along with the risks of liability, reputational tarnish, or other forms of injury offering participants may incur, is an informational asymmetry mitigant. ↑

Anita Indira Anand, The Efficiency of Direct Public Offerings, 7 J. SMALL & EMERGING BUS. L. 433, 435 (2003). ↑

Id. at 438. ↑

Institutional (or “sophisticated”) investors typically conduct independent due diligence before acquiring securities in a registered offering. Moreover, FINRA regulations state that the scope of an underwriter’s due diligence “will necessarily depend upon [factors such as] whether the offerees are retail investors or more sophisticated institutional investors.” FINRA, Regulatory Notice 10-22, Obligation of Broker-Dealers to Conduct Reasonable Investigations in Regulation D Offerings (2010). The ABA Due Diligence Task Force Report echoes this sentiment when it identifies the following factors a relevant to underwriter due diligence: (i) “the degree to which participants in the market—particularly professional investors, rating agencies, and securities analysts—obtain and disseminate information about issuers,” (ii) “the degree to which relevant investors rely on a rating assigned to the underwritten securities by an independent rating agency,” and (iii) “the degree to which relevant investors have independent access to information and credit judgments about the issuer.” Comm. on Fed. Reg. of Sec., Report of Task Force on Sellers’ Due Diligence and Similar Defenses Under the Federal Securities Laws, 48 BUS. LAW 1185, 1240 (“ABA Due Diligence Task Force Report”). Thus, institutional investors are more likely to possess a range of information about the offering as well as internal expertise to efficiently complete a valuation of the securities being offered. Anita Indira Anand, The Efficiency of Direct Public Offerings, 7 J. SMALL & EMERGING BUS. L. 433, 445-446 (2003). Commonly, such investors conduct their own research and monitor factors such as historical performance and prior offering results. Id. at 446. As a result, “the underwriter’s information function becomes less important for institutional shareholders because of their level of sophistication and the active manner in which they pursue their investments. Indeed, institutional investors’ relative sophistication means that they are less in need of the underwriter’s services….” Id. ↑

See, e.g., Arthur B. Laby, Differentiating Gatekeepers, 1 BROOK. J. CORP., FIN. & COMM. L. Vol. I (2006) 119; Peter B. Oh, Gatekeeping, 29 J. CORP. L. 735, (Summer 2004); Reinier H. Kraakman, Gatekeepers: The Anatomy of a Third-Party Enforcement Strategy, II.1 J.L. & ECON. 54 (1986). ↑

Lawrence Cunningham, Beyond Liability: Rewarding Effective Gatekeepers, 92 MINN. L. REV. 323, 328 (2007). ↑

John Coffee, The Attorney as Gatekeeper: An Agenda for the SEC, 103 COLUM. L. REV. 1293, 1296 (June 2003). ↑

Andrew F. Tuch, The Limits of Gatekeeper Liability, 73 WASH. & LEE L. REV. ONLINE 619 (2017). ↑

Liability may also arise in other ways including under common law. ↑

15 U.S.C. § 78a et seq. ↑

15 U.S.C. § 77k. ↑

Section 15 of the Securities Act provides that any person who controls a person liable under Section 11 or Section 12 of the Securities Act is liable jointly and severally with and to the same extent as the controlled person. The term “controls” is broadly defined for purposes of this section, and the concept of control can include directors, officers, and principal stockholders, depending on the specific facts and circumstances. 15 U.S.C. § 77o. ↑