The authors will present a webinar titled “Liability Management Transactions: From Basics to Derivatives” on August 7, 2025, at 1 pm ET. Register now to attend and deepen your knowledge of topics related to this article, free for ABA Business Law Section members.

Liability management transactions (“LMTs”), at their core, are maneuvers whereby a favored (or “winning”) group of lenders to a given borrower extract value from an unfavored (or “losing”) group of lenders to the same borrower. LMTs have recently gained significant momentum and—from the perspective of unfavored lenders—notoriety.

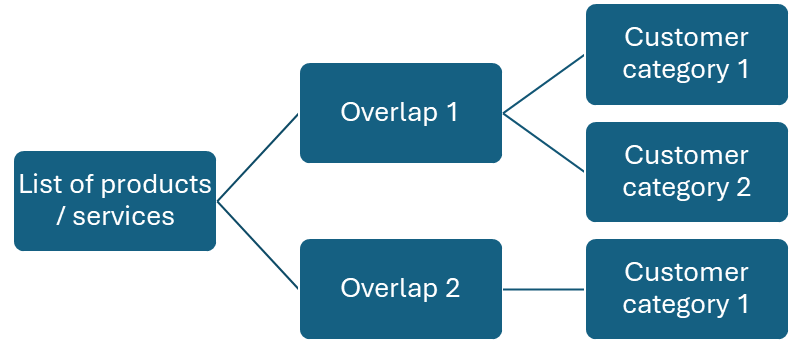

Although structures continue to evolve, LMTs generally fall into three primary buckets.

- Drop-Down Transactions: Sometimes referred to as “trap door” transactions, drop-downs involve the borrower moving assets outside of the reach of the borrower’s primary lenders. The borrower then uses those same assets to raise new debt from existing or third-party lenders, typically on more favorable terms than previously provided by the primary lenders.

- Uptier Transactions: Substantially all credit agreements are rooted in the understanding that lenders in a given tranche of debt receive pro rata treatment. Uptier transactions upend this notion, whereby a subset of existing (and similarly situated) lenders to a given borrower move their loans into a new tranche featuring more senior payment and lien priority terms (sometimes alongside a new money component)—leaving the remaining (unfavored) lenders with subordinated payment terms and lien priority.

- Double-Dip Transactions: A more recent market innovation, the double-dip transaction is structured to use available secured debt capacity to provide a single new money loan with two separate claims against the assets of the borrower credit group. The proceeds of the new loan are used to fund an intercompany loan to an affiliate of the same borrower. The lenders’ new loan is then secured by both (i) the borrower’s repayment obligations and assets and (ii) the intercompany loan (and related guarantees and security) issued by the affiliate of the borrower.

The Administrative Agent

In a customary credit agreement, the administrative agent serves as a liaison between the borrower and the syndicate lenders, coordinating communications and facilitating operational efficiencies. In addition to routine matters involving the collection and disbursement of payments and providing access to financial reporting, agents play a pivotal role in assessing the necessary lender approval thresholds for proposed borrower actions. This latter function is of paramount importance in a contested LMT where, for example, a group of unfavored lenders may seek to block an uptier transaction by asserting that unanimous or affected lender consent is required to alter the pro rata treatment of lenders.

In this capacity, the duties of the administrative agent are delineated strictly as mechanical and administrative in nature. Separately, customary credit agreements typically provide that the administrative agent is not a trustee or fiduciary for either the borrower or the syndicate lenders. Unless granted the specific authority to take a unilateral action under the credit agreement or unless a given action requires unanimous or supermajority consent, the administrative agent must act at the direction of the “Required Lenders” (typically, lenders with more than 50 percent of outstanding loans and/or commitments under the credit agreement). In addition, when matters exceed the administrative agent’s explicit authority under the credit agreement (including matters of judgment), it is prudent for the administrative agent to consult with (and, ultimately, take direction from) the Required Lenders.

As LMTs have continued to proliferate and clear the lending market, administrative agents would be well served to take a measured and calibrated approach when evaluating requests from sponsors (and their related portfolio company borrowers) to consider, and sanction, LMTs.

Key Considerations in Drop-Down Transactions

The investment and restricted payments covenants in the credit agreement are central to drop-down transactions. A borrower utilizes negotiated baskets embedded in these covenants to transfer assets from a restricted subsidiary (that is, a subsidiary subject to the constraints of the credit agreement) to an unrestricted subsidiary (that is, one that is not).

While variations of this structure have existed for many years, J.Crew, Envision, and other drop-down transactions that have ensued highlight the types of determinations that administrative agents must undertake when analyzing the borrower’s use of covenant baskets.

As a preliminary matter, the administrative agent should evaluate whether the credit agreement contains protective terms (often referred to as a “J.Crew blocker”) that serve to prevent the borrower’s transfer of material assets in a specified asset category without the consent of the lenders. While intellectual property is commonly designated as the asset class subject to a J.Crew blocker, when negotiating the credit agreement, the administrative agent should confirm which asset classes are genuinely material for that particular borrower. For instance, the crown jewel of a mining company might be its leasehold rights—making those rights the appropriate asset class to designate as “material” for purposes of the J.Crew blocker.

If a J.Crew blocker is not contained in the credit agreement, the administrative agent must then confirm that the subsidiary that will receive the asset has been appropriately designated as an unrestricted subsidiary. Designation of an unrestricted subsidiary is generally construed as an investment (and typically utilizes the investment basket) under a credit agreement. In addition to calculating basket capacity under the investment covenant, when confirming the classification of a subsidiary as unrestricted, the administrative agent must determine if any other requirements that apply—such as pro forma financial covenant compliance, or the absence of any defaults or events of defaults—have been satisfied.

Given that basket capacity is a key feature when assessing the permissibility of a drop-down transaction, in addition to analyzing the investment basket, administrative agents should also consider the permitted indebtedness and asset disposition covenants (and related baskets). Furthermore, they should analyze whether any cumulative credit basket is available (sometimes referred to as “stacking”) and if the unallocated portion of a debt, investment, or restricted payments basket can be reallocated to another basket (sometimes referred to as “reclassifying”). An additional provision to consider is the “transactions with affiliates” covenant and whether it may be breached by the proposed drop-down.

Given that borrowers consistently seek to obtain operational flexibility, while lenders regularly endeavor to impose guardrails to mitigate collateral leakage, basket calculations are routinely subject to intense negotiations. As administrative agents analyze LMTs, there are a number of techniques that can be employed to provide additional lender protections. Administrative agents can, for example, require a borrower to certify its basket calculations (and provide the lenders with related supporting materials). Another useful approach is to require that the borrower provide a generally unqualified factual statement that the proposed transaction is permitted by the terms of the credit agreement. With respect to investments made by the borrower (using the investment basket), the lenders can insist on a borrower officer’s certificate that specifies the valuation mechanics of the proposed investment. For example, the lenders can require that the value of the transferred asset (in excess of a certain threshold) be validated by a third-party appraisal or valuation statement.

In the drop-down context, the operational mechanics of releasing a guarantor or lien on a transferred asset should also be considered. Administrative agents should evaluate whether liens and guarantees are automatically released in a proposed LMT. Careful scrutiny of the administrative agent’s ability to facilitate these releases is warranted. In practice, administrative agents need to consider whether they are required to provide the syndicate lenders with notice of a borrower-requested lien release. As a further step, some administrative agents now require the borrower to certify that the administrative agent is authorized to release its lien on designated collateral under the terms of the credit agreement.

Key Considerations in Uptier Transactions

In an uptier transaction, the administrative agent must first determine the consent threshold for the proposed credit agreement amendment intended to authorize the non–pro rata treatment of lenders. Does taking this step require an affected lender vote or a more permissive Required Lender vote?

In further analyzing whether an uptiering amendment is permissible, regardless of whether some level of syndicate lender approval is required, the administrative agent should evaluate whether the proposed amendment functionally modifies a sacred right (such as the maturity date of the facility—which modification would require an affected lender vote).

With respect to the required intercreditor agreement that will delineate the rights and remedies of the existing “unfavored” lenders vis-a-vis the “favored” lenders, the administrative agent should evaluate whether the credit agreement simply “authorizes” the administrative agent to enter into the intercreditor or “authorizes and instructs” the agent to do so, as this latter formulation is more protective of the administrative agent. An attendant consideration is whether the credit agreement requires unanimous syndicate lender consent to subordinate existing liens. Unlike drop-down transactions, a borrower’s certification with respect to the analytical issues associated with uptier transactions is less prevalent in the market.

In addition to voting rights, the debt repurchase mechanics are another area of focus in uptier transactions. Many credit agreements restrict a borrower (and its related sponsor and affiliates) from repurchasing debt under the credit agreement (subject to carefully negotiated thresholds and exceptions). The market has not reached a consensus standard as to whether a privately negotiated purchase of debt constitutes an open market purchase (which is a common exception to the non–pro rata treatment of lenders under a credit agreement). Agents must also consider if there are other mechanisms to facilitate the non–pro rata treatment of the “favored lenders.”

Key Considerations in Double-Dip Transactions

In the ever-evolving world of LMTs, the double-dip transaction represents a market development that poses a unique set of challenges for administrative agents, made more so by the fact that the structure has not been fully adjudicated in a bankruptcy court. A borrower’s ability to implement a double-dip stems from secured debt capacity under the credit agreement and the interpretation of how pari passu debt capacity can be applied. Since the double-dip primarily relies on pari passu baskets, administrative agents can carve out intercompany loans from those baskets in an attempt to limit their adoption in the market. Another alternative is to restrict a borrower’s ability to incur intercompany loans exclusively to the intercompany debt basket, which requires subordination and other protections. As a practical matter, these nuances are still being refined, and effective LMT blockers for double-dips are not yet pervasive in loan documentation.

Blockers: Not Created Equally

While the efficacy of LMT blockers has been the subject of much commentary, it is critical to note that not all LMT blockers are the same. Debtor-in-possession exceptions can cut a wide swath into intended protections. While what is referred to as a “Chewy blocker” is intended to prevent a subsidiary guarantor from being released from its guarantee obligations, borrowers do attempt to negotiate baskets around these release mechanics. Additionally, in response to borrowers using a drop-down transaction to remove assets from the collateral base and then, instead of raising debt, raising preferred equity and issuing a dividend to the borrower, some lenders have adopted what is referred to as a “Pluralsight blocker,” which restricts or otherwise imposes limitations with respect to any contemplated preferred equity issuance of an obligor. However, this blocker is not prevalent in the current market.

Conclusion

As administrative agents navigate drop-down, uptiering, and double-dip LMTs and their various permutations, considerations with respect to voting rights, basket capacity, and borrower certification will remain key areas of focus. Subtle changes in language, such as an agent “acting on the instruction” of the lenders, can provide incremental protections that further mitigate administrative agent risks. Finally, agents should bear in mind that for any LMT blocker that offers purported protections, there is likely an impending workaround being crafted. As such, facilitating thorough diligence and transparent communications between the borrower and the lenders will be key to balancing the various competing interests in LMTs.

David Ebroon is an Assistant General Counsel at J.P. Morgan Chase, and serves on the Commercial and Investment Banking Legal Team. He is the Head of Legal for each of Mid-Corporate and Capital & Advisory Solutions.

Arleen Nand is a shareholder at Greenberg Traurig, LLP.

The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of their employer, its or their clients or any of its or their respective affiliates. This article is for general information purposes and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice.