As the business owners of the baby boomer generation reach retirement age and seek liquidity for their life-long investments, many will need an exit strategy to transition ownership of their businesses. This is often a very difficult time for a business owner. The owner wants and needs to receive fair value for the business, but often does not want the business to be acquired by a third party who may relocate the business outside of the owner’s community. The owner may also want to reward loyal employees who have made significant contributions to the business’ successes. If the owner is willing to receive fair market value rather than a strategic value, an employee stock ownership plan, commonly known as an “ESOP,” may provide a practical exit strategy. Although an ESOP is one of several alternatives that will enable an owner to gain liquidity and transition ownership, ESOP strategies have several advantages that are unavailable with alternative transition strategies. Unfortunately, there is a lot of misinformation circulating about ESOPs. This article will describe ESOPs, discuss how they provide a reasonable exit strategy for a business owner, and review the advantages and disadvantages of selling all or a portion of a business to an ESOP.

What Is an ESOP?

An ESOP is a type of qualified retirement plan similar to a profit-sharing plan, except that an ESOP is required by statute to invest primarily in shares of stock of the ESOP sponsor. Unlike other qualified retirement plans, ESOPs are specifically permitted to finance the purchase of employer stock by borrowing from the corporation or selling shareholders. ESOPs are, therefore not just tax-qualified retirement plans, but also tools of corporate finance. When Congress authorized ESOPs, the intent was to use tax incentives to provide an exit strategy for owners of privately held businesses that are not readily marketable, while at the same time creating ownership opportunities and retirement assets for working-class Americans. According to the National Center for Employee Ownership, there were an estimated 7,000 ESOP-owned companies with around 13.5 million plan participants in 2011 (the most recent year for which information is available). Importantly, as retirement vehicles, ESOPs held over $942 billion in retirement plan assets in 2011.

How Does an ESOP Acquire Ownership?

In a typical leveraged ESOP transaction, a corporation’s board of directors adopts an ESOP plan and trust and appoints an independent ESOP trustee. After obtaining an appraisal of the corporation’s equity, the ESOP trustee negotiates the purchase of all or a portion of the corporation’s issued and outstanding stock from one or more selling shareholders. In general, the corporation sponsoring the ESOP will borrow a portion of the purchase price from an outside lender (the “outside loan”) and immediately loan the proceeds of the outside loan to the ESOP (the “inside loan”) so that the ESOP can purchase shares. The two-phase loan process is used because lenders are generally unwilling to comply with restrictive ERISA loan requirements. If only a portion of the purchase price is funded with senior financing, the remaining portion of the purchase price will generally be funded through the issuance of subordinated promissory notes to the selling shareholders, whereby the sellers receive a rate of interest appropriate for subordinated debt. See Diagram A.

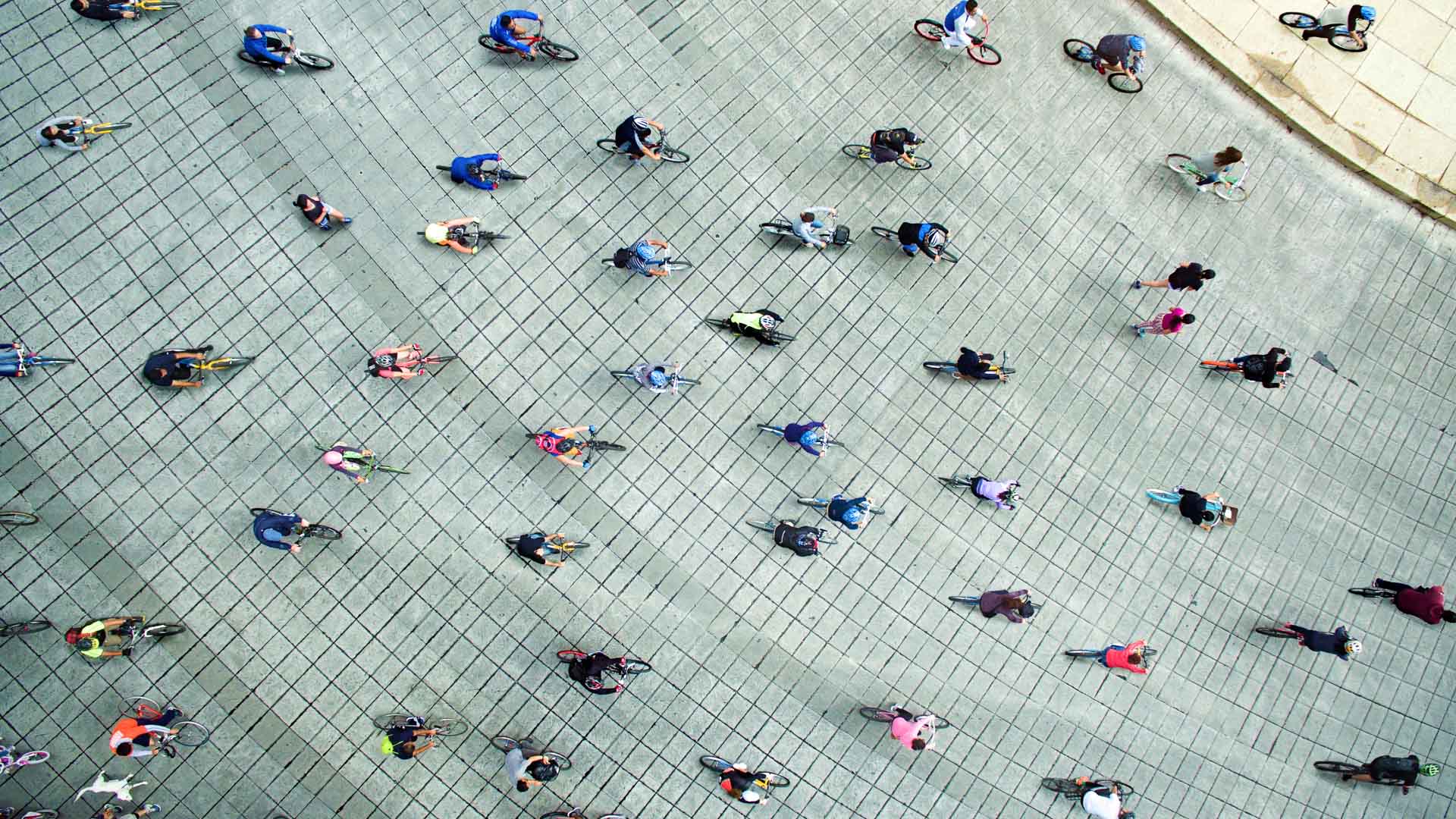

Diagram A

To provide the ESOP the funds necessary to repay the inside loan, the corporation is required to make tax-deductible contributions to the ESOP each year, similar to contributions to a profit-sharing plan. Upon receipt of these annual contributions, the ESOP trustee immediately uses the funds to make payments to the corporation on the inside loan. In addition to these contributions made to the ESOP by the corporation, the corporation can declare and issue tax-deductible dividends (C corporation) or earnings distributions (S corporation) on shares of the corporation’s stock held by the ESOP which, in addition to employer contributions, can be used by the ESOP trustee to pay down the inside loan. Shares purchased by the ESOP from selling shareholders (or the corporation) are held in a “suspense account” within the ESOP trust. As the ESOP trustee makes its annual principal and interest payment on the inside loan, shares of the corporation’s stock acquired by the ESOP from the selling shareholders (or corporation) are released from the suspense account and allocated to the ESOP accounts of employees participating in the ESOP. See Diagram B.

Diagram B

As opposed to a leveraged transaction described above, some ESOPs acquire shares from a business owner without the corporation incurring any debt. Unless the corporation has significant available cash on its balance sheet, this approach requires some advanced planning. For example, one strategy for selling the business to the ESOP without incurring debt is to prefund the ESOP trust. Under this approach, the corporation initially establishes a qualified profit-sharing plan, with the intention to convert the plan to an ESOP at a future time. The corporation makes cash contributions to the plan, which contributions are allocated to employees’ accounts and invested by the plan’s trustee. After a sufficient amount of cash accumulates in the employees’ accounts, the plan converts to an ESOP and the ESOP trustee uses the amounts allocated to the employees’ accounts to purchase shares from the selling shareholder(s), which shares are then allocated to the employees’ accounts based on each employee’s account balance.

Tax Benefits of an ESOP Exit Strategy

The tax benefits of the ESOP exit strategy accrue to the selling shareholder, the corporation, and the employees who participate in the ESOP. The tax benefits to the selling shareholder and corporation vary depending on whether the corporation is taxed as an S corporation or as a C corporation.

Selling Shareholders

Section 1042 of the Internal Revenue Code (the “Code”) provides that, if the ESOP sponsor is a C corporation, shareholders selling to the ESOP may elect to defer the recognition of gain on the sale if: (i) the ESOP owns at least 30 percent of the shares or value of the corporation following the sale; (ii) the selling shareholder held the shares for at least three years prior to the sale; and (iii) the selling shareholder uses the sales proceeds to purchase “qualified replacement property” or “QRP” (defined generally as any security of a domestic operating corporation). The gain can be deferred as long as the selling shareholder holds the QRP. Further, if the shareholder dies while holding the QRP, the QRP receives a “stepped-up” tax basis, meaning the gains realized on the sale to the ESOP will never be recognized.

Although this Section 1042 gain deferral election is not available to an S corporation shareholder (without a conversion to a C corporation), there are significant benefits for an S corporation shareholder selling to an ESOP. The primary benefit is that because of the extremely beneficial tax treatment of an ESOP-owned S corporation, an S corporation typically has greater cash flow on a post-transaction basis to repay the ESOP loan and, therefore, can often purchase 100 percent of the corporation’s stock in a single transaction rather than engaging in multiple transactions over a number of years to acquire full ownership of the corporation.

Corporation

An ESOP sponsor also receives significant tax benefits. Up to certain statutory limits, employer contributions to an ESOP are tax-deductible, whether such contributions are allocated directly to participants’ accounts or used to make payments on the inside ESOP loan.

If the ESOP sponsor is an S corporation, that portion of the corporation’s earnings attributable to the ESOP’s ownership interest is not subject to federal income tax (or state income tax in most states). Thus, if the ESOP is the sole shareholder of an S corporation, the corporation will function much like a tax-exempt entity. How can this be? As a pass-through entity, an S corporation does not pay federal income taxes at the corporate level. Rather, the income tax liability is passed through to the shareholders which, if the sole shareholder is a tax-exempt ESOP trust, means that no federal income taxes will be paid on the corporation’s earnings until participants’ ESOP accounts are distributed. See Diagram C.

Diagram C

Example of Benefit of ESOP in an “S” Corporation | ||

S Corp Net Income $5,000,000 with No ESOP | S Corp Net Income $5,000,000 with 50% ESOP Ownership | S Corp Net Income $5,000,000 with 100% ESOP Ownership |

Corporate Tax: $0 | Corporate Tax: $0 | Corporate Tax: $0 |

Individual Shareholders’ Taxes: on $5,000,000 @ 40% = $2,000,000 | Individual Shareholders’ Taxes: on $2,500,000 @ 40% = $1,000,000 | ESOP Shareholders’ Taxes on $5,000,000 = $0 |

Total “Tax Dividend” = $2,000,000 | ESOP Shareholder Tax on $2,500,000 = $0 ESOP’s Share of Tax Dividend = $1,000,000 | ESOP’s “Share” of Historic Tax Dividends = $2,000,000 or the Corporation doesn’t have to pay a tax dividend and may retain the entire $2,000,000 |

ESOP Participants

Employees participating in an ESOP also receive favorable tax treatment. As in other tax-qualified retirement plans, tax on amounts allocated to participants’ ESOP accounts is deferred until distribution of the participants’ accounts. Additionally, distributions from ESOP are eligible to be rolled over to an IRA or another eligible retirement plan. Further, if the ESOP permits participants to receive distributions of their ESOP accounts in shares of employer securities, the tax on any appreciation of the shares while allocated to the participants’ account (i.e., the “net unrealized appreciation”) is: (i) deferred until the distributed stock is subsequently sold; and (ii) taxed as capital gains rather than ordinary income. Another benefit of an ESOP is that, unlike a 401(k) plan, which generally requires an employee to defer his or her own salary to receive additional employer contributions, most ESOPs are funded solely by employer contributions, meaning that an employee does not have to defer compensation in order to share in the ESOP benefits.

Non-Tax Benefits of an ESOP Exit Strategy

In addition to the tax advantages described above, an ESOP exit strategy provides many non-tax benefits that business owners should consider, depending on the business owner’s goals for transitioning the business. One advantage of selling to an ESOP is the creation of a ready market for the business owner’s stock, providing a buyer for the business when there is no other readily apparent buyer. Because the ESOP provides a market for the shares, the marketability discount applied when valuing shares in an ESOP is typically only 5 percent to 10 percent. In addition, an ESOP permits a business owner who so desires to gradually transition ownership over an extended period of time, allowing the business owner to remain actively involved in the corporation. This is particularly helpful, for example, if the business owner desires some liquidity but is not yet ready to sell 100 percent of his or her ownership interest. The owner can sell a minority interest in an initial transaction and sell his or her remaining ownership interest in later transactions.

Many owners would prefer to sell their businesses to the next level of management, but rarely do these individuals have the funds to acquire the business. A partial or full sale to an ESOP allows the business owner to get the desired liquidity without selling to a competitor or other third party. Senior managers can be rewarded through equity-based performance plans. In addition, although ESOPs are broad-based plans that generally provide a retirement benefit to all of the corporation’s employees, shares are typically allocated to participants’ accounts in proportion to their relative compensation, which will generally result in the more highly-compensated management employees receiving larger ESOP allocations.

Further, unlike a sale to a private equity firm or strategic buyer, there is often no need to implement operational restructuring prior to executing an ESOP exit strategy. This is because the corporation’s management team and employees remain in place post-transaction. Also, because the corporation is not “shopped” (e.g., by an investment bank), it is not necessary to risk releasing confidential information to any competitors who may otherwise be bidding to buy the corporation. Additionally, an ESOP is a long-term financial investor that will not be seeking to sell the corporation after a relatively short time period.

Importantly with respect to an ESOP-owned corporation operating as an ongoing concern, numerous studies have shown that employee-owned companies tend to outperform their peers by motivating and rewarding employees through their equity interests in the corporation.

Special Considerations in Implementing an ESOP Exit Strategy

Selling to an ESOP also involves considerations beyond those relating to tax and non-tax benefits. First, it is essential to keep in mind that the ESOP is a qualified retirement plan governed not only by the Code, but also by the fiduciary and disclosure rules of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA). The sale to an ESOP is not an “inside transaction” in the sense that the terms of the transaction may be unfair. Rather, the ESOP trustee is subject to a high fiduciary duty standard, and must assure that the ESOP does not purchase shares of stock at a price which exceeds “fair market value,” as such term is defined under Section 3(18) of ERISA. In addition, the ESOP trustee’s financial advisor must be independent of all parties to a transaction in which an ESOP acquires stock from a selling shareholder (or corporation), which requirement is rigorously enforced by the U.S. Department of Labor. The need to comply with ERISA and the Code will potentially involve added cost to executing an ESOP exit strategy, including the need to retain an independent trustee, independent financial advisor, and independent legal counsel to advise the ESOP trustee. The corporation also needs to engage qualified ESOP counsel experienced with ESOP stock purchase transactions, in addition to its corporate counsel.

Another consideration involves the ongoing administrative, fiduciary, and legal costs associated with an ESOP exit strategy that might not be present in a typical sale to a third party. In addition to expenses incurred to maintain the ESOP plan and trust documents and costs for a recordkeeper/third-party administrator to administer the ESOP, a corporation will incur annual expenses of an ESOP trustee and the costs of an annual valuation to determine an updated share value for ESOP administration purposes.

There are limits on the amount of tax-deductible contributions that can be made to the ESOP each year. Additionally, if a shareholder of a C corporation elects Code Section 1042 gain deferral in a sale to an ESOP, the selling shareholder and certain family members will be restricted from participating in the ESOP, even if they are employees of the corporation. In addition, in an S corporation ESOP, because the potential tax benefit is so significant, Code Section 409(p) provides an anti-abuse provision that prohibits any one participant or family from receiving excessive share allocations in the ESOP or in other synthetic equity issued by the corporation. Compliance with these restrictions must be monitored and maintained.

Finally, as the ESOP matures, participants will become eligible to receive distributions of their ESOP stock accounts as they retire and terminate employment. Because the corporation is obligated to purchase the shares for their fair market value, the corporation will have a stock repurchase obligation that must be monitored and funded on an ongoing basis.

Characteristics of Good ESOP Candidates

When considering whether an ESOP may be a reasonable exit strategy for a business owner, it is important to consider various characteristics of both the owner and the business.

Selling Shareholders

Owners should be looking for a fair valuation rather than a strategic valuation. Because ERISA prohibits the ESOP trustee from paying more than fair market value, a shareholder who wants to get every last penny for the corporation, regardless of the impact on the employees or the community, is probably not a good candidate for an ESOP. A business owner interested in rewarding those employees who helped build the business, who wants to preserve his or her legacy and the independence of the corporation in a tax-efficient transaction, will more likely be a good candidate for the ESOP exit strategy.

Corporation

The corporation should also have certain characteristics to be a viable ESOP sponsor. Profitability, good financial reporting and controls are necessary, as is capacity for additional leverage. Most importantly, however, it is critical to have a good management team ready to lead the business. The ESOP trustee is exercising its fiduciary duty when making a decision to purchase shares of a selling shareholder. Lack of a strong management team will negatively affect the fair market value of the business, and might even result in an ESOP trustee’s refusal to buy the shares. Unlike a private equity investor, an ESOP trustee does not want to run the business or serve on the board. Therefore, without a strong management team to grow the business and create the necessary cash flow to repay the debt associated with the stock purchase, the ESOP trustee will likely pass on the stock purchase.

Corporate Governance in an ESOP Company

Confusion exists relating to the corporate governance of a business following implementation of an ESOP exit strategy. In this regard, it is important to remember that the corporation will continue to operate as a corporation following an ESOP transaction. The corporation will continue to be governed in accordance with its articles of incorporation and bylaws and the corporate laws of the state of incorporation. An ESOP sponsor’s board of directors will continue to monitor management, and management will continue to make all day-to-day operational decisions. Employees will still be employees and will not take over the management or control of the corporation.

The ESOP trustee will not run the business of an ESOP sponsor and typically will not be directly represented on its board of directors. The ESOP is a shareholder of the corporation sponsoring the ESOP, and votes the shares held in the ESOP trust. In privately-owned corporations, ESOP participants generally do not direct the voting of the shares in their ESOP accounts except on significant corporate matters that require shareholder approval under state law, including a merger, sale of all or substantially all the assets, recapitalization, reorganization, liquidation, or dissolution. An ESOP trustee may either be a discretionary trustee, with full discretion to vote the ESOP shares on most matters, or a directed trustee, voting only as directed by the board of directors or a committee appointed by the board, unless the ESOP trustee determines such direction violates ERISA. As a result, if the ESOP holds a majority of the stock in a corporation, corporate governance is somewhat circular, inasmuch as the board of directors appoints the ESOP trustee and the ESOP trustee elects the board of directors.

Why Should I Talk to My Client About an ESOP?

Although you may not be an expert on the ESOP exit strategy, basic knowledge about an ESOP is important for all business and M&A attorneys to have in their toolboxes. Especially because of ERISA fiduciary requirements applicable to ESOPs, companies considering an ESOP exit should consult an experienced ESOP attorney who can work with business and M&A attorneys to effect the required transactions. As is the case in other business acquisition transactions, a due diligence review of the corporation will be undertaken by the buyer and its advisors, and the buyer’s financial advisor will assist the buyer in determining the equity value the ESOP will offer for the corporation. In addition, there are typical financing documents, a stock purchase agreement with customary representations, warranties, covenants, and conditions. It is also critically important that all parties understand the tax benefits and the constraints associated with transition to an ESOP.

Because of the possibility that an ESOP transaction will be best suited to meeting a business owner’s needs for an exit strategy, and due to the significant tax benefits available, it is important that business attorneys be acquainted with ESOPs and prepared to present ESOP strategies to their clients when discussing the available exit alternatives.