Most nonprofits depend on funding from a constantly shifting and frequently perilous landscape of government, foundation, and individual sources, which means that most nonprofits are—or should be—constantly assessing their operations and missions to determine how they can continue to maximize impact. Smart nonprofits look at mergers and combinations proactively and strategically as a way to strengthen effectiveness, expand reach, achieve efficiencies, improve the quality of existing services, leverage assets, access more diversified funding sources and fundraising capabilities, enhance complementary missions, and create greater impact in the communities they serve. Because the nonprofit sector is highly fragmented, opportunities for strategic combinations abound.

Nonprofit combinations can take many forms and pose issues similar to traditional M&A deals in the for-profit sector and require deployment of the familiar building blocks of a for-profit transaction, i.e., letters of intent, term sheets, due diligence, and negotiating definitive documents. However, nonprofit corporations are subject to unique legal and tax regimes, which can create numerous traps for unwary business lawyers looking to assist their local nonprofit in exploring possible deals. After one of our M&A partners exclaimed, deep into a session spent counseling a regional nonprofit client exploring a national acquisition strategy, “What is all this talk about understanding the local community? When are we going to start talking about money?!” we gained a renewed appreciation that the M&A work we do for our nonprofit clients is, in some respects, mysterious to our partners with corporate transactional practices.

This article provides a high-level discussion of issues and considerations unique to nonprofit M&A deals and provides a guide for business attorneys representing a nonprofit organization in a combination.

Key Distinctions between Nonprofit and For-Profit Combinations

Governance, Not Money

Because nonprofit corporations are not owned by individuals, the primary focus in a nonprofit combination is control of the combined organization. The size and composition of the governing board, representation of the constituents in the combined organization’s governance, and the allocation of governance rights among potentially more than one legal entity are major deal points that arise early on in a nonprofit combination.

In contrast to typical for-profit M&A transactions in which there is significant emphasis on maximizing the value and benefit of the transaction to owners or shareholders, in a nonprofit combination, there may not be any purchase price or financial consideration. Instead, program service commitments, adherence to mission and use of existing charitable assets are all major deal points.

This is not to say that financial resources are never an issue. In many cases, a nonprofit will seek specific capital or funding commitments in connection with their combined operations going forward. And, in combinations between a nonprofit and a for-profit entity, state and federal law require money to be central to the deal structure. The value of the nonprofit should be evaluated by an expert in nonprofit valuations and the for-profit must pay a purchase price which is at least fair market value. Those funds do not, however, get paid to any individual. Instead, they must remain dedicated to charitable purposes following the combination.

Tax-Exempt Status

The term “nonprofit” is most often used to describe an entity that has two key characteristics. First, it is formed as a nonprofit legal entity under state law. Most commonly this is a nonprofit corporation, but depending on the state in which it is formed, nonprofits may also be formed as nonprofit LLCs, religious organizations, charitable trusts, or in other forms. Second, the most common form of tax-exemption classification is Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. This is a tax designation that exempts the organization from paying federal income tax on its activities and earnings except in limited circumstances and is one of the few classifications which permit donations to the corporation to be eligible for the charitable contribution deduction.

All organizations described in Code Section 501(c)(3) are also classified under the Internal Revenue Code as either public charities or private foundations. It is critical to identify the tax-exemption and public charity classification of each nonprofit organization up front and to determine what impact, if any, the proposed combination may have on either or both classifications.

State Law Issues

Nonprofit organizations, including nonprofit corporations and trusts, can be subject to state laws which are not modern and sometimes present challenges in the context of a combination or merger. For example, state law may require the State Attorney General, or even the district court, to approve a merger involving a nonprofit. Such approvals can delay a proposed transaction and catch the participants by surprise. Understanding the state laws at issue early in a transaction can be critical to achieving the desired time line.

Also, because nonprofit organizations do not have shareholders to answer to, there is usually a state authority with the legal obligation to oversee a nonprofit’s use of its charitable assets. This role is commonly held by the Attorney General or Department of State and those offices take particular interest when nonprofits pursue a combination. Finally, in many states, assets held by a charitable organization, regardless of corporate form, may be subject to additional restrictions as to their use or disposition.

Members vs. Shareholders

Where for-profit corporations have owners or shareholders whose financial interests are paramount in a business combination, some nonprofits have a similar, but distinct, role served by individual or nonprofit corporate “members.” Members may not have financial interests in the nonprofit, but they usually have specific governance rights, including authority to approve or reject major corporate transactions, and may also have the power to appoint some or all of the nonprofit’s board, approve changes to its governing documents, and approve other corporate changes.

If either nonprofit constituent has members, the combination must be managed carefully to ensure that members are accorded all voting and approval rights under state law and the nonprofit’s governing documents. Member meetings may be held infrequently (annually) and in some cases, it may take more than one meeting to approve significant corporate changes. Identifying whether there are corporate members, their identity and rights, is a critical initial step in any merger or combination conversation.

Mission Focus

Fiduciary duties of nonprofit directors run to the nonprofit corporation and the advancement of its mission. A nonprofit’s “mission” includes the social ends that the organization and its programs seek to produce, such as healthy children and families, an enlightened public, or empowered youth. When a nonprofit is considering a combination, its Board of Directors must determine whether it is in the best interest of the nonprofit and is in furtherance of its mission. The board is also entitled to consider the effect of the combination on all of its constituents, including its employees and the clients and community it serves. It should consider both the proposed partner and the legal structure of the combination in making this determination. A nonprofit’s mission is not defined solely by the sum of its services, so an expansion or reduction in services could still be consistent with its overarching mission. Negotiations should be tested against this mission focus on a regular basis.

Common Legal Models of Nonprofit Combinations

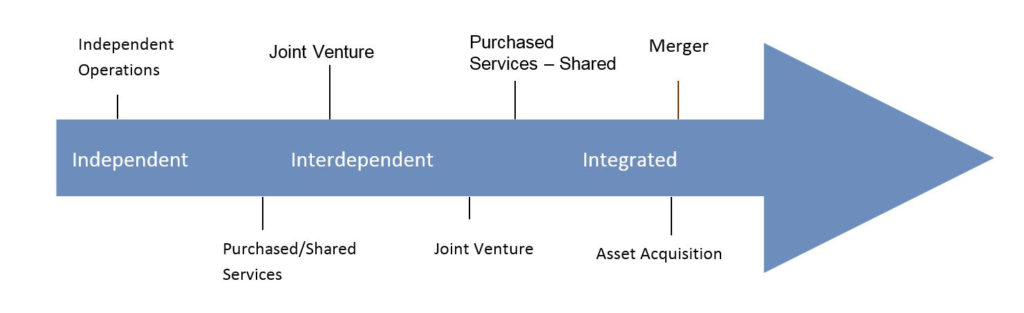

A wide range of legal structures are available for combinations and collaborations between nonprofits. These structures fall along a range based on the degree of integration of the nonprofit constituents. Below are some of the most common types of nonprofit combinations, from least integrated to most highly integrated:

Independent: Contractual Ventures. There are wide-ranging opportunities for nonprofits to remain separate but engage in collaborative efforts.

- Outsourcing under Service Agreements. Nonprofits may find it most efficient to outsource programs or operational areas to a third party that is either a nonprofit or for-profit entity. This may be limited to administrative areas such as marketing, facilities management, or back-office operations such as billing and collections. If a nonprofit is providing services, it must carefully determine whether the provision of such services is related to its tax-exempt purposes. If it is not, the nonprofit may be required to pay tax on the income from the arrangement in the form of unrelated business income tax, and if the activity is substantial it could jeopardize the nonprofit’s tax-exempt status. If a for-profit is providing services to a nonprofit, the IRS requires that the arrangement be on fair market or more favorable terms to the nonprofit. Either arrangement should have clear documentation of terms including services provided, responsibilities, payment, term and termination, and allocation of liability.

- Collaborations and Shared Services Arrangements. Two or more nonprofits may enter into a collaboration to jointly fund or operate a specific project or program in furtherance of each of their missions. These typically involve services that both entities need and currently perform separately, such as administrative functions, operational functions, and programmatic functions. This can eliminate duplicative personnel and equipment and lead to greater efficiencies. The arrangement should be in a written agreement which allocates operational responsibilities, establishes a financial structure, defines the key elements of the program, outlines reporting obligations, and defines the governance structure for oversight of the program. A shared services arrangement can be an initial step toward more full integration of the nonprofit participants, allowing them to build a trust relationship based on their joint operations and to gradually increase their shared functions over time.

Interdependent: Structural Combinations. Several options exist for nonprofits to achieve a more committed combination of legal structures while still retaining some separation of legal existence, control, and/or governance between the two organizations. A few examples:

- Joint Ventures. A nonprofit may enter into a joint venture with another organization in which they both make equity investments and share governance rights in an existing or new entity that engages in activities related to the organizations’ exempt purposes. If a nonprofit undertakes a joint venture that is not related to its exempt purposes, it should be analyzed to determine whether it is a prudent investment and whether it may produce unrelated business income. The joint venture partner may be a for-profit or nonprofit entity. Where a for-profit and nonprofit participate in a joint venture together, losses and profits must be allocated based on capitalization of the joint venture entity, and capital contributions must be valued at fair market value. In contrast, if the joint venture partners are nonprofits and share a common mission, there may be some flexibility to negotiate the economic terms of the venture.

- Parent-Subsidiary. In this structure, the articles and bylaws of one nonprofit are amended to designate the other as its sole corporate member. Each organization retains its own board of directors, but the member organization has special governance rights over the other nonprofit, which may include, for example, the right to appoint all or some directors to the board, approve changes to its governing documents, approve budgets and significant capital commitments, and have other “reserved powers” as to significant corporate matters. In a slightly more integrated form of parent-subsidiary structure, one nonprofit becomes the sole corporate member of another and both organizations are governed by the board of directors of the acquirer. Representatives of the acquired organization may be granted seats on the member’s board of directors for a period of time to facilitate transition and continued constituency engagement.

- Super Parent. Alternatively, a new entity may be created to serve as a “super parent” of both nonprofits. The super parent serves as the sole member of each nonprofit constituent and often the super parent board of directors is composed of representatives of each of the nonprofit organizations, at least for a transition period. Long-term, the super parent may have a self-perpetuating board. The super parent’s board oversees and governs both organizations and provides an overarching strategic, operational and governance mechanism over both organizations.

Dependent: Highly Integrated Structures. The most highly integrated structures are whole-entity combinations such as a merger, consolidation or transfer of substantially all assets in which two or more nonprofit organizations ultimately function as one legal entity. This option is often pursued where the nonprofit partners have strong congruence of mission and where they conduct similar or complementary programming, such that each organization believes that bringing the two partners together will substantially increase their ability to further their own mission. Critical factors in these structures involve ensuring preservation of the charitable missions of the combining nonprofits, and respecting donor intent related to charitable assets.

- Asset Transfer and Dissolution. As in the for-profit context, nonprofits may have special or significant liabilities or tax risks that can be best managed by pursuing a transfer of substantially all assets from one nonprofit to another followed by the winding down and dissolution of the transferring entity. Liabilities in particular can be managed in a way that helps reduce the risk they present to the combined entity, and it still achieves all or virtually all programming of both organizations being combined into a single entity. If desired, areas of operations involving high risk or known liabilities can be transferred into a subsidiary of the acquiring nonprofit in order to provide additional liability protection. As in a for-profit deal, there can be a purchase price paid by the buyer for the assets being transferred by the seller, with such purchase price being used to support the same charitable mission of the seller.

- Merger. A legal merger is the full legal combination of two or more nonprofit organizations in which all assets and liabilities of the merging entities combine by operation of law into one operating entity. Either entity may serve as the “surviving” entity, which continues in existence while the other merger partner ceases to have separate legal existence. Some states also permit “consolidation” in which neither nonprofit is the surviving entity and both merge into a newly formed nonprofit, which can be useful in deals that involve a “merger of equals.” Key issues involve the governance structure of the survivor, naming of the entity, stakeholder interests, control and ongoing support of existing programs and agreements, continuation of staff, physical location of operations, and identifying legal liabilities and legal compliance risks. Importantly, under the nonprofit laws of many states, a statutory merger is the only way to be certain that bequests to the nonprofit constituent(s) ultimately pass by law to the benefit of the surviving corporation.

Checklist of Unique Issues in Nonprofit Collaborations

Collaborations involving nonprofit, tax-exempt organizations can introduce a number of other regulatory complexities and compliance issues. Below is a high-level issue-spotting checklist of some key issues that can arise in a nonprofit transaction:

- Tax-Exempt Financing. Many nonprofits take advantage of tax-exempt financing to finance their facilities. If either or both nonprofit constituents have tax-exempt bonds or notes in place, these financing documents should be carefully reviewed to determine whether the proposed form of collaboration will impact the ability to keep financing in place, including obligations to bondholders.

- Executive Compensation/Payouts. It is not uncommon for transactions between for-profit entities to involve special payouts to executives or other key employees as a performance bonus, retention incentive, or for other reasons. The 501(c)(3) rules impose strict limitations on compensation to individuals that will limit the nonprofit’s ability to offer certain types of payouts in a transaction, including a requirement that the total compensation paid to any individual be “reasonable” compensation for the services provided by the individual to the nonprofit based on comparable market compensation data. State laws may also restrict the ability to make any such payments or may cap them at a prescribed amount.

- Property Tax Exemption. Many nonprofits are exempt from paying property taxes on owned real estate based on the charitable nature of activities they conduct using the property. Property tax rules vary by state, but typically exemption is not automatically granted based solely on 501(c)(3) status. Therefore, the parties should analyze the potential effect of the transaction on the organizations’ qualification for property tax exemption.

- Notice to State Authorities. As noted above, nonprofit transactions may require advance notice and/or consent of one or more state agencies charged with oversight of nonprofit and charitable assets, such as the attorney general or secretary of state.

- Restricted Gifts and Donor Intent. Many nonprofits have received gifts from donors that are designated for a specific purpose. These restricted gifts must be carefully reviewed and tracked in a combination to ensure that they are used in furtherance of the donor’s intent following the transaction. Any changes in the proposed use of funds must be done in compliance with state law and with donor consent. Where donors are unavailable, court approval may be required.

- Employee Benefits. Many benefits plans offered by nonprofit employers are different than for-profit employer plans so employee benefit counsel with appropriate expertise should be consulted. In particular, any transition of employees between a nonprofit and for-profit combination partner will involve additional complexity as these employees must be transitioned from one plan type to another.

- Special Considerations in Nonprofit / For-Profit Collaborations. Collaborations between nonprofit and for-profit entities will be carefully scrutinized by state and federal authorities to ensure that no charitable assets flow to the benefit of the for-profit partner. These transactions are still possible but must be carefully structured to be on at least fair market value or more favorable terms to the nonprofit partner and otherwise include important safeguards to protect the tax-exempt status of the nonprofit partner.

Conclusion

While many aspects of nonprofit collaborations are consistent with for-profit transactions, there are critical differences that influence all stages of the deal, from negotiation points to due diligence to legal structures to post-closing integration. It is beneficial to include a nonprofit and tax exemption specialist on your deal team to help issue-spot these and to efficiently advise on complex tax exemption matters, nonprofit corporate governance structures, tax-exempt financing, or other issues identified above.