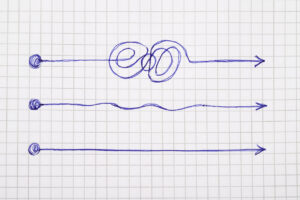

Disagreements between parties over the purchase price in an acquisition often can be driven by their differing views of the selling company’s future performance and cash flows. To get to “yes,” parties may bridge their valuation differences by agreeing to an earnout, meaning they set agreed-upon metrics regarding the company’s post-closing performance and measure those metrics after closing. The seller then “earns” additional payments if the post-closing performance validates its valuation position. Parties must carefully define the details of how they will measure the earnout payment. The 2019 ABA Private Target Mergers and Acquisitions Deal Points Study (which examined 151 deals valued between $30 million and $750 million from 2018 and the first quarter of 2019) found that approximately 27 percent of those deals included earnout provisions.

The well-documented problem is that the earnout bridge the parties take to close their valuation differences often leads to litigation over whether the earnout was met or why it was not met.[1] Two recent decisions from the Complex Commercial Litigation Division of the Delaware Superior Court demonstrate how careful drafting affects the resultant litigation risk.

Collab9, LLC v. En Pointe Techs. Sales, LLC

In Collab9, LLC v. En Pointe Techs. Sales, LLC,[2] a seller argued that the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing required the purchaser to maximize an earnout provision in an asset purchase agreement (APA). The seller alleged the purchaser breached the duty of good faith and fair dealing by “maintaining financial records in a way that made it impracticable to accurately determine the correct amounts of Earn-Out payments; creating a sham entity to move revenue off [its] books; and renewing certain contracts or transferring sales persons or accounts as a means of minimizing Adjusted Gross Profit.”[3]

The APA provided, however, that the “Purchaser shall have sole discretion with regard to all matters relating to the operation of the Business. Purchaser shall have no express or implied obligation to the Seller, . . . to seek to maximize the Earn Out payment . . . .”[4]

The purchaser moved to dismiss, pointing to the “sole discretion” provision it bargained for as defeating any implied covenant claim. The court agreed and dismissed the claim. Such “comprehensive and explicit” terms “demonstrate that the parties contemplated that a dispute might arise concerning the operation of the business post-closing, specifically whether the purchaser was acting in a manner that maximized the Earn Out.”[5] The terms that “granted broad rights to the purchaser to operate the business as it sees fit” meant the implied covenant could not give the seller rights it had “failed to secure for themselves at the bargaining table.”[6]

Merrit Quarum v. Mitchell International, Inc.

In Merrit Quarum v. Mitchell International, Inc.,[7] specific contractual language imposing post-closing obligations on the purchaser led to a different outcome. At issue was an earnout agreement, entered into by the parties in connection with a stock purchase agreement, that contained three provisions addressing the post-closing obligations of the purchaser. First, although it had “the power to direct the management, strategy, and decisions” post-closing, the purchaser agreed it would “act in good faith and in a commercially reasonable manner to avoid taking actions that would reasonably be expected to materially reduce the” earnout.[8] Second, the purchaser agreed to “act in good faith and use commercially reasonable efforts to present and promote the [acquired company’s products] to customers that could reasonably be expected to utilize” them.[9] And third, the purchaser agreed to upgrade or build a bridge between the companies’ systems, within six months of closing, to allow the purchasers to sell the acquired products to its existing customers and to assist in calculating the earnout.[10]

In an action asserting, among other things, noncompliance with the earnout agreement, the seller asserted breach of contract, not implied covenant, claims. Unlike Collab9, the court denied the purchaser’s motion to dismiss for some of the seller’s earnout allegations, focusing on the first and third obligations in the earnout agreement.

As to the first obligation in the earnout agreement, the court viewed the provision as a negative covenant requiring the purchaser to refrain from “positive action[s]” that reasonably could be expected to reduce the earnout or impede calculating the earnout. That obligation did not extend, however, to “avoiding inaction” because extending that obligation would “place the power to manage the company in” the hands of the seller.[11] In analyzing the complaint’s specific allegations, the court found that many fell short of asserting positive action. Those allegations focused on “decisions and strategies [the purchaser] could have pursued but did not,” such as consulting with the seller on marketing.[12] The claims that survived the motion to dismiss focused on positive actions such as “routinely cancel[ing] regularly scheduled calls to prevent [the seller] from promoting and selling” the products, and improper accounting decisions concerning minimum thresholds for bills, and diverting revenue to different products to avoid paying the earnout.[13]

With respect to the third obligation in the earnout agreement, the purchaser argued the seller could not plead damages resulting from the purchaser’s decision to build an alternative bridge between the parties’ systems. Relying primarily on Delaware’s minimal pleading standard for damages—which does not require pleading “damages with precision or specificity”—the court concluded it was reasonable to infer from the agreement that a specific solution was necessary to provide services to customers and calculate the earnout amount, and failing to build that solution could constitute damages.[14]

Takeaways

These decisions reflect how Delaware courts understand the incentives underlying, and details of, earnout provisions and hold parties to their bargain. Concessions today might get the deal done, but purchasers must be aware that they may be agreeing to significant restrictions on how they run the business post-closing, and as Merrit Quarum demonstrates, concomitant litigation risk if the earnout is not met. That holds true for sellers, who have the opposite incentives, and could give away their ability to hold the purchasers accountable post-closing. Said differently, through the lens of analyzing future litigation (especially at the pleading stage), purchasers face more risk (and sellers have stronger leverage) from having to comply with specific earnout provisions that impose post-closing obligations on the purchaser. In analyzing earnout provisions that do not require specific obligations and grant the purchaser significant discretion to operate the business, implied covenant claims are an uphill climb because Delaware courts refuse to use the covenant to give parties “contractual protections that they failed to secure for themselves at the bargaining table.”[15]

The 2019 ABA Private Target Mergers and Acquisitions Deal Points Study indicates that, at least in the available data, purchasers are “winning” these negotiations when they occur. Of the subset of deals containing earnouts, only about 30 percent include a covenant to run the business consistent with past practice or to maximize the earnout.

[1] Aveta Inc. v. Bengoa, 986 A.2d 1166, 1173 (Del. Ch. 2009 (“Earn outs frequently give rise to disputes, and prudent parties contract for mechanisms to resolve those disputes efficiently and effectively.”).

[2] 2019 WL 4454412 (Del. Super. Ct. Sept. 17, 2019).

[3] Id. at *1.

[4] Id. at *2.

[5] Id. at *2.

[6] Id. at *3 (quoting Aspen Advisors LLC v. United Artists Theatre Co., 843 A.2d 697, 707 (Del. Ch. 2004)).

[7] 2020 WL 351291 (Del. Super. Ct. Jan. 21, 2020).

[8] Id. at *2.

[9] Id.

[10] Id.

[11] Id. at *5.

[12] Id.

[13] Id.

[14] Id. at *7.

[15] Aspen Advisors LLC v. United Artists Theatre Co., 843 A.2d 697, 707 (Del. Ch. 2004), aff’d, 861 A.2d 1251 (Del. 2004).