Robert Dickie and Peter Russo’s book, Financial Statement Analysis and Business Valuation for the Practical Lawyer, Third Edition, guides lawyers through key principles of corporate finance and accounting with direction on how to analyze the income statement, balance sheet, and cash flow statements. The guide helps lawyers gain a working knowledge of financial concepts, terminology, and documents and an understanding of basic and advanced techniques of valuing companies.

This is the first in a series of articles intended to provide a working knowledge of financial statements, terms, and concepts, especially as that knowledge is useful in the practice of law. For business lawyers, the language of business is finance, and it pays to be equipped to understand the business dimension as well as the law.

There are three main financial statements—namely, the balance sheet, the income statement, and the cash flow statement. This article will discuss the balance sheet, also known as the statement of financial position. The balance sheet is a “snapshot” of a company’s position at a particular point in time. The report takes a simple approach: at any given moment, what you own (assets) less what you owe (liabilities) is what you are “worth” (shareholders’ equity). It’s important to note that “worth” for financial reporting purposes is very different from the market value of the company. Here, we simply mean worth from a reporting perspective.

Assets are economic resources available for use in the future. Liabilities are obligations to outsiders, and equity is the claim of the owners after the obligations. Expressed as an equation,

Assets (owned) – Liabilities (owed) = Equity (worth).

More simply, A – L = E. This equation can also be expressed as A = L + E; this is commonly referred to as the balance sheet equation. The balance sheet presents assets on one side, equal to liabilities and equity on the other. Another way to think about the balance sheet is that assets are what the company owns—the resources they have available to use in the future to run the company; liabilities and equity are where the money comes from to buy those resources.

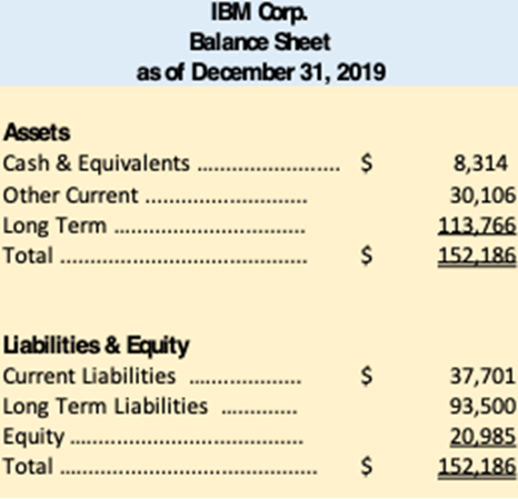

Here is a summary version of IBM’s most recent year-end balance sheet.

Note the time stamp, “as of December 31, 2019.” As of the close of business on December 31, 2019, IBM froze its books to count up where it was. Also note that these numbers are presented in millions of dollars; the cash balance of $8,314 means $8.3 billion of cash.

Assets

Assets are the tangible and intangible resources owned by the company. Almost all asset values are based on the cost to acquire these assets, not the current value of the assets. This is obviously an important distinction and is why we can’t use the reported asset amounts to determine the value of a company. For example, if IBM purchased land 50 years ago for $1 million, it’s still on their balance sheet for that amount, even though today it may be worth exponentially more.

In addition to cash, IBM had other current and long-term assets, amounting to just over $150 billion in resources owned by the company at that point in time. On the bottom half of the balance sheet are the sources for the capital used to acquire and use those resources. A distinction is made between short-term (current) and long-term assets and liabilities; current assets are expected to become cash within the next 12 months, whereas current liabilities are expected to be satisfied within the same 12 months.

The most common short-term assets are cash (and cash equivalents), accounts receivable, and inventory. Typically, the most significant of the long-term assets are “property, plant and equipment” (also referred to as “fixed” assets), goodwill, and intangible assets. There may also be deferred tax assets if the company has paid a tax to the IRS but not yet reflected the expense under the accounting rules.

If a company has goodwill or intangible assets, it is most likely because it has made an acquisition, and the purchase price exceeded the fair market value of the acquired company’s “net assets” (defined as assets – liabilities). With a few exceptions, internally produced intellectual property does not appear on the balance sheet as an asset. Instead, the costs to create the intellectual property are included as expenses on the income statement.

This can be important. For example, a company’s balance sheet may report more liabilities than assets; however, it likely owns economic assets that are not reflected on its balance sheet. Coca Cola’s most valuable asset, for example, is its formula, but that is not on Coke’s balance sheet because the costs to develop it were long since expensed, and GAAP makes no attempt to reflect the fair value of assets.

Sidebar 1: Deferred Taxes

There can be differences between when a company reports taxes for accounting purposes and when it pays them to the IRS. For instance, current tax rules allow a company to depreciate an asset more rapidly on their tax return than they do on their financial statements. This means depreciation expense this year will be higher on the tax return, and taxable income will be less than accounting income, lowering the taxes due this year. This is a temporary difference in taxable income and accounting income; total depreciation expense is the same over the life of the asset, but is allocated differently over the years. This creates a deferred tax liability because expenses have been taken earlier for the tax computation and eventually will have to be paid. Conversely, if the company accrues a workmen’s compensation expense but has not yet made the payment and thus cannot yet deduct the sum on its tax return, then the expense on its income statement will be higher than the deduction on its tax return, and its tax liability will be greater than the tax paid to the IRS. This results in a deferred tax asset for accounting purposes.

It is most important to understand that GAAP accounting rules rely upon significant judgment by management in valuing assets. For example, there are two different methods to value accounts receivable, four different methods to value inventory, and six different methods to value fixed assets. Management is allowed to decide which methods it uses (note that management must consistently apply the method it chooses and can’t change methods year to year). In addition, these methods require estimates of such things as the collectability of receivables, the potential obsolescence of inventory, and the useful life of fixed assets. These are just examples of the inherent judgment involved in all assets, with the exception of cash.

When a company is struggling financially, it is most important to understand what the numbers mean and the context of how the numbers are determined. First, remember that the reported amount of the assets do not purport to be the current market values. Second, management may be so biased as to use the allowable judgment to overstate the value of an asset in order to meet a loan covenant, or understate expenses to improve profit.

In an economic crisis liquidity, the ready access to the cash needed to fund operations becomes a particularly important indicator of a company’s ability to survive. Is the company’s cash position deteriorating, and if so how quickly? Does it have additional sources of cash available? Are the assets really worth as much as the amount reflected on the balance sheet? In considering whether assets are shown at the lower of cost or market value, has management considered current market conditions? (See Sidebar 2.) Might the market value of its assets, less its liabilities, actually exceed the going concern value of the company? If so, should the company consider liquidating its assets and distributing the proceeds to its creditors and shareholders?

When performing due diligence, each asset should be looked at and probed. Have any values been impaired? Are all receivables collectible in the current economic environment? Is inventory all usable, or is obsolescence a concern? Even in the case of buildings, the market values may have declined if there are vacancies or the tenants can’t pay the rent.

Sidebar 2: The Value of an Asset Can Change with Context

During the second quarter of 2020, Delta Airlines recorded an “impairment” charge of almost $2.2 billion. U.S. GAAP requires that the reported dollar amount of an asset cannot exceed its estimated future value to the company. Delta reduced the value attributable to certain aircraft. According to the notes to its financial statements, this write-down reflected the company’s current plans for these aircraft in light of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s important to note that this write-down did not imply that these aircraft were in any way damaged or obsolete. The lower value on their balance sheet simply reflects the current situation; they have less utility to the company under current conditions, and their liquidation value is probably impaired at this time as well. What management is doing here is exactly what GAAP requires.

At the same time, management says that it has evaluated the reported value of its goodwill and intangibles and has concluded that those values have not been impaired, meaning that they are worth at least what they are being carried at on the balance sheet. Note that management summarizes the impact of the pandemic on the financial condition and operations of the company in a single note to the financials. Any user of the financial statements would be well advised to read it carefully.

In a crisis, a key first step is to consider the company’s strategy and plans to survive the crisis and then examine the assets from the standpoint of their likely value under that scenario. At the risk of overstating it, the reported value of the assets on the balance sheet, both individually and collectively, should not be mistaken for their market values or their liquidation values in a time of crisis.

Liabilities

Liabilities are obligations of the business. This includes obligations to employees, customers, vendors, and lenders. These are separated into short-term (those due within one year) and long-term liabilities. Liabilities are generally of two types: (1) noninterest-bearing liabilities, and (2) debt, which bears interest and has a due date. The usual short-term liabilities are accounts payable (monies owed to vendors) and accrued liabilities (estimated liabilities). It also includes any principal amounts on debt due in the next 12 months. If a company is in the enviable position of receiving cash from its customers before earning the revenue (like subscriptions paid in advance), the unearned or deferred revenue will be shown as a current liability. The most common long-term liabilities are long-term debt, deferred tax liabilities, lease obligations, and pension liabilities.

One issue that arises for all companies is “contingent” liabilities. These are liabilities that may inure to the company based on some underlying future event. For example, if a company is sued by a customer for a product liability claim, the company will be obligated only if they lose the lawsuit. In this case, the liability is not included on the balance sheet unless it is highly probable that the company will lose the lawsuit and the judgement can be reasonably estimated. Up to that point it may be required to disclose the potential liability in the footnotes, unless it is highly unlikely to lose the suit. The determination of the likelihood of winning or losing is made by management based on information from legal counsel.

Solvency refers to the comparison of a company’s assets with its liabilities. Insolvency means that the accounting value of the liabilities exceeds the accounting value of the assets (because A = L+ E, if liabilities exceed assets, the equity is actually negative). The term “insolvency” can also refer to a company unable to meet its obligations as they come due, though that may also be referred to as “cash flow insolvency” or a “liquidity problem.” This may have significant consequences, such as possible violation of financial or other contractual covenants. Under the corporate laws of many states, if there is balance sheet insolvency, payment of dividends or share repurchases can result in personal liability to directors.

Especially in times of stress, we are concerned about a company’s liquidity—its ability to meet its financial obligations as they come due. The most common measure of liquidity is current assets (those expected to generate cash within the next 12 months) divided by current liabilities (those that will consume cash during that same period). This is called the “current ratio.” However, recognizing that inventory is likely to be of little use in meeting short-term liabilities if revenues are down, a more rigorous measure counts current assets minus inventory in the numerator. That is called the “quick ratio.”

Hopefully, before a company faces either insolvency or liquidity problems, financial covenants provide lenders with an early warning that the situation may be deteriorating and may need attention. Legal counsel should advise their clients to be proactive in communicating concerns about performance against their covenants and to help them negotiate covenants that both take into account expected performance and allow flexibility where warranted.

Equity

Equity represents the claims of the owners on the company. Equity comes in two forms, money invested by the owners (contributed capital) and company-generated profits that are left in the company (retained earnings) and can be used to purchase additional assets, pay dividends, or reacquire shares. As of December 31, 2019, IBM had assets of $152.2 billion and owed $131.2 billion; the balance of the assets ($21.0 billion) was funded by the owners. (Note that, of course, Assets = Liabilities + Equity).

Contributed capital is typically reported in two elements: “common stock” (reported at par value—the “minimum value of the shares”) and “additional paid in capital” (the amounts received over par value). Also commonly included in equity is “treasury stock.” This amount, a negative number, represents the company’s shares that were repurchased from the equity markets. This is a common way to manage the financing of the company.

It is important to note that there are only three sources of capital available to any company for the purchase of assets. The company can: (1) borrow the money (liabilities), (2) sell equity positions to the owners (contributed capital), or (3) earn money on its own from running its business at a profit and leaving these funds in the company (retained earnings). Every company combines these three sources to fund the purchase of its assets and decides how much will come from each of the three sources.

This mix of liabilities and equity is called the “capital structure” of the company. Deciding on an appropriate capital structure is a key part of any company’s strategy. Debt is less expensive than equity and does not dilute the ownership of the shareholders. However, adding debt increases the company’s financial risk—the risk that it will not be able to meet its financial obligations when due. Over the last few decades, the availability of low-cost debt has motivated many companies to add a greater proportion of debt (leverage). The long-term success of this strategy depends upon the company’s ability to meet its debt obligations. It will be important to watch these companies carefully during this economic crisis. Is that increased level of debt affordable under the current scenario?

A company borrows money and sells equity to buy assets. These assets are employed to produce something of value for a market: products and/or services. The company sells the products and/or services produced by the assets to its customers, generating revenue and hopefully profits. The income statement reports on these activities, revenue, and expenses. Our next article looks at the reporting context for the income statement, what the numbers mean, and how to read the results.