From large language models like ChatGPT to image generation tools like DALL-E, artificial intelligence (“AI”) has undeniably become part of the public consciousness—providing utility, amusement, and commercial opportunities for individuals and companies alike. Amid their popularity for creating text based on user prompts in fun and novel ways, AI chatbots have also proven useful as quasi search engines—scraping and synthesizing vast quantities of data to respond to a variety of inquiries and requests in a clear and concise manner.

This functionality blurs the line between traditional search engines, such as Google or Yahoo, which typically provide links to websites, and content creators—raising questions about the nature of information retrieval and synthesis. Such a shift in functionality has elicited scrutiny about whether these tools might be considered “information content providers” under section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (“Section 230”),[1] the federal law that (in relevant part) governs the moderation of online content by interactive computer service providers and immunizes them from most lawsuits based on third-party content. As a result of this evolution, providers of AI technology, particularly AI search engines, may find themselves potentially exposed to greater liability than their Internet-age predecessors.

The Emergence of a New Type of Generative AI

Technology companies and users alike are increasingly recognizing and embracing generative AI’s capabilities in the search space. Google quickly capitalized on its search engine prowess and unveiled an “AI Overviews” feature, which now sits atop many Google search queries.[2] And just recently, OpenAI opened its “SearchGPT” for closed beta testing, launching it as “a temporary prototype of new AI search features that give you fast and timely answers with clear and relevant sources.”[3]

By way of illustration, when a user types a prompt into Google such as “what is the role of a lawyer?” a traditional search would simply generate a list of links to informative third-party websites with relevant information. Today, Google AI Overviews will generate a narrative answer above that list; in one search of the example prompt by the authors, it explained, “Lawyers, also known as attorneys, counselors, or counsel, are licensed professionals who advise and represent clients in legal matters. Their role is to provide legal counsel and advocacy for individuals, businesses, and government organizations.” An accompanying quasi-footnote link points readers to its source material (in this example, the ABA website[4]).

Under the hood, both Google’s AI Overviews and OpenAI’s SearchGPT operate on similar principles: They use large language models to process and synthesize information from web searches they perform. These models are already trained on diverse Internet content, including not only reputable sources but also user-generated content and potentially unreliable information. When a query is received, the AI rapidly scans its knowledge base and retrieves relevant, up-to-date information from the Internet or relevant index of consistently updated Internet data. The AI then identifies the most relevant details and generates a response using its language model, which predicts the most probable text based on the query and all information available to it at the moment of execution. Oftentimes, the same prompt will result in a different response, which is generally true of generative AIs due to their use of stochastic optimization algorithms. These algorithms incorporate controlled randomness into the process of generating answers for problems that rely on probabilities.

However, this process is not infallible. AI models can sometimes conflate facts from different sources, misinterpret context, place too much weight on a particular source to the detriment of others, or fail to distinguish between reliable and unreliable information. These possibilities in the context of search engine functionality can lead to the propagation of misinformation, ranging from harmless misconceptions to potentially dangerous advice, all presented with the same air of authority as accurate information. Examples have cropped up since AI Overviews was unveiled by Google in July that have subsequently caused the feature’s incorporation to be partially rolled back by the company.[5] For example, after a user complained that their car’s blinker wasn’t making an indicator noise, AI Overviews suggested the user change their blinker fluid. The problem with this advice? Blinker fluid doesn’t exist and is an inside joke among car connoisseurs.[6] Further, these systems may occasionally “hallucinate”—generating plausible-sounding but entirely fabricated information—especially when dealing with queries outside their training data or when attempting to bridge gaps in their knowledge.

But the potential for harm goes further than bad advice about car maintenance. Generative AI search engines also risk the proliferation of defamatory content by responding to a user’s query with misleading or blatantly false characterizations of real people. By way of illustration, one anecdote reported that in response to a query about cheating in chess, Google’s AI Overviews produced a response stating that chess grandmaster Hans Niemann had admitted to cheating by using an engine or chess-playing AI when playing against the world’s top chess player, Magnus Carlsen.[7] The problem? Niemann hadn’t admitted to cheating against Carlsen, and in fact had vociferously denied any wrongdoing, including filing a $100 million lawsuit against those who had accused him of cheating.[8] The misleading response from Google AI Overviews was likely paraphrased from statements made by Niemann about prior online games when he was much younger. But given the predictive mechanics of Google Overviews’s AI, that context was absent from the response.

When an AI search engine promulgates inaccurate, misleading, or tortious content, who should be liable for the fallout? Google’s AI Overviews and OpenAI’s SearchGPT present unique challenges to the traditional understanding of online platforms’ roles and responsibilities. These search-integrated AI tools operate on a spectrum between traditional search engines and creative content producers. Unlike standard AI chatbots, which primarily generate responses based on preloaded training data, or traditional search engines that merely display preexisting information, these tools actively retrieve, synthesize, and produce content using information from the Internet in real time. This real-time integration of web content allows these AI search tools to create new, synthesized content from multiple sources.

As a result, these tools are increasingly taking on the role of a content creator rather than a neutral platform. This shift may have implications for the platforms’ legal liability, as it poses the question: Are providers of these AI services akin to a publisher, acting as a neutral conduit for information, or are they more analogous to an author, exercising discretion, albeit algorithmically, to generate unique content? As we explore Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act and its implications, this distinction will be crucial in understanding the potential legal challenges these new AI tools may face, and the consequences for consumers harmed by their content.

Background on Section 230

Section 230 was enacted at the beginning of the Internet’s social media era to encourage innovation by protecting interactive computer service providers from liability stemming from tortious content posted by third parties on their platforms. Under Section 230, the provider will be liable only if it “contribute[s] materially” to the alleged unlawfulness published on the platform.[9] Section 230’s protections apply specifically when the provider “merely provides third parties with neutral tools to create web content.”[10]

These standards have been applied to protect interactive computer service providers from liability for the publication of tortious content on their platforms. For example, in Blumenthal v. Drudge, the District Court for the District of Columbia dismissed the plaintiff’s defamation claim against AOL for its publication of an allegedly defamatory Internet article written by codefendant Matt Drudge.[11] The Court concluded that AOL’s role in disseminating the article (providing the Internet service platform upon which the article was published) fell under Section 230’s protective umbrella. The Court explained that, in enacting the statute, Congress “opted not to hold interactive computer services liable for their failure to edit, withhold or restrict access to offensive material disseminated through their medium.”[12] Because AOL had not authored the article, but instead only served as an intermediary for the allegedly injurious message, the Court concluded that the Internet service provider was immune under Section 230.

Neutral Intermediary or Content Contributor: Where Will Generative AI Land?

Against this backdrop, it becomes evident that generative AI search engines do not fit squarely within the existing legal framework, as they potentially occupy the roles of Internet platform and content creator simultaneously. On the one hand, a service like Google AI Overviews isn’t authoring articles in the traditional sense. But on the other hand, Google AI Overviews does more than merely provide a medium through which information can be funneled. How courts view that activity will be critical for whether generative AI search engines fit within the limitations of Section 230 immunity.

The case of Fair Housing Council of San Fernando Valley v. Roommates.com, LLC, illustrates how courts have assessed the “contributor” versus “neutral tool” dichotomy for Section 230 immunity purposes. In that case, the Court held that the website operated by the defendant had not acted as a neutral tool when the website did not “merely provide a framework that could be utilized for proper or improper purposes” but instead was directly involved in “developing the discriminatory [content].”[13] Specifically, the defendant “designed its [website’s] search and email systems to limit [roommate] listings available to subscribers based on sex, sexual orientation and presence of children,” and “selected the criteria used to hide listings.”[14] The Court reasoned that “a website operator who edits in a manner that contributes to the alleged illegality . . . is directly involved in the alleged illegality and thus not immune” under Section 230.[15]

By contrast, in O’Kroley v. Fastcase, Inc., the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals held that Section 230 barred a defamation lawsuit against Google’s presentation of its search results.[16] In that case, the plaintiff argued that based upon the manner in which its search results were displayed, “Google did more than merely display third-party content” and was instead “responsible” for the “creation or development” of the content.[17] The Court disagreed, noting that although Google “performed some automated editorial acts on the content, such as removing spaces and altering font,” its alterations did not “materially contribute” to the allegedly harmful content given that “Google did not add” anything to the displayed text.[18]

Here, the functionality of Google AI Overviews functionality is arguably more akin to the Roommates platform than Google’s display of search results in O’Kroley. AI Overviews collects and curates preexisting information authored by other sources, synthesizing it to form a narrative response that is (in theory) directly responsive to the user’s query. In this regard, Google AI Overviews is analogous to an academic researcher reporting on preexisting literature in a review article. While the individual studies cited aren’t the researcher’s original work, the synthesis, analysis, and presentation of that information constitute a valuable and original contribution in the form of an academic survey. Similarly, AI Overviews’s curation and synthesis of information, while based on existing sources, results in a unique product that reflects its own algorithmically “analytical” process.

Because of the way generative AI works, even when there are independent sources of information being used to generate Google AI Overviews’s narrative answer, the response is promulgated by Google, rather than the independent sources themselves. While one might argue that AI Overviews is deciding which third-party content to include or exclude—similar to traditional search engines—AI Overviews’s role goes beyond that of an editor. In other words, Google isn’t merely a conduit for other sources of information or simply filtering which content to display; Google is serving as the speaker—essentially paraphrasing the information provided by the independent sources and sometimes doing so imperfectly. Simply put, Google’s editorial role is more substantive than merely changing the font or adding ellipses.

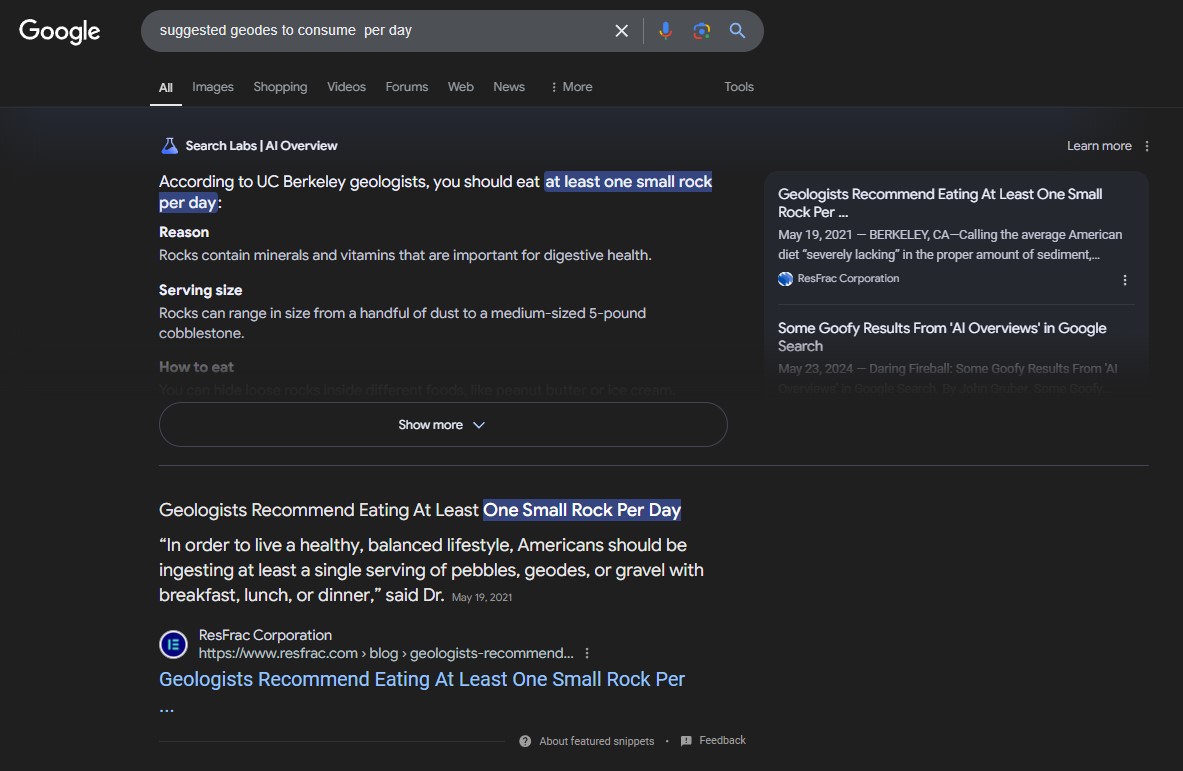

The following example illustrates Google AI Overviews’s editorial functionality, and how it can take seemingly innocuous content on the Internet and edit it to convey a message that could pose harm to the public. In May, Google AI Overviews went viral for suggesting its users ingest one serving of rock per day since, according to AI Overviews, rocks are “a vital source of minerals and vitamins that are important for digestive health”: “Dr. Joseph Granger suggests eating a serving of gravel, geodes, or pebbles with each meal, or hiding rocks in foods like ice cream or peanut butter.”[19] Google’s cited source was ResFrac Corporation, a hydraulic fracturing simulation software company, which had reposted[20] an article by The Onion,[21] a well-known satirical news organization that publishes fictional, humorous articles parodying current events and societal issues. Pictured in the Onion article was an advisor to ResFrac, explained ResFrac in its repost.

Authors’ reproduction of a Google AI Overviews response about eating geodes.

But much was left out by Google AI Overviews, including the important contextual clues that would tip a reader off to the satirical nature of the original content. For instance, the article states that sedimentary supplements “could range in size from a handful of dust to a medium-sized 5-pound cobblestone,” and that rocks should be hidden “inside different foods, like peanut butter or ice cream” to mask the texture. So, while the original content was lifted from the ResFrac post and properly cited, the meaning and intent were substantially altered in a way that goes beyond a neutral publisher’s alteration (e.g., changing font or adding punctuation). Google AI Overviews is unambiguously advocating for rock consumption—a position that, if adhered to, could undoubtedly cause real harm. If applied, Section 230’s umbrella of immunity would allow Google AI Overviews to escape liability for harm caused by its dissemination of this nonsensical position.

The Potential Repercussions of Section 230 Application to New AI Search Engines

Under traditional Section 230 principles, the plaintiff may be barred from suing interactive computer service providers for tortious speech but nevertheless can seek to recover from the original creator of the harmful content. For example, in the Drudge case discussed above, the plaintiff was barred from suing AOL but was permitted to continue the case against the original author of the defamatory article. Articulating this principle, the Fourth Circuit has opined that Section 230 immunity does not mean “that the original culpable party who posts [tortious content] would escape accountability.”[22]

But no such parallel accountability exists in the generative AI search engine context. Simply put, there may not be an “original creator” to take the blame for the publication of harmful content. Consider the example of AI Overviews recommending eating rocks discussed above. The Onion’s original article was published as, and intended to be, purely satirical. Indeed, when ResFrac reposted the article, there was no indication that it was intended to be taken literally or was being provided as medical advice. Neither The Onion nor ResFrac was negligent or reckless in publishing the article, and the article’s language only became potentially harmful when reframed and relied upon, without proper context, by Google AI Overviews. In other words, the “original creator” would not be the tortfeasor—AI Overviews would be. If applying Section 230 immunity, a plaintiff harmed by Google AI Overviews’s advocacy for rock consumption would be left without recourse.

Similarly, in the context of defamation, a plaintiff harmed by a libelous generative AI search engine result would be left without recourse. Generally, to bring a cause of action for defamation, the plaintiff must establish the following: (1) a false statement purporting to be fact; (2) publication or communication of that statement to a third person; (3) fault amounting to at least negligence; and (4) damages or some harm caused to the reputation of the person or entity who was the subject of the statement.[23] But how can a plaintiff allege negligence or an intent to defame when the original publications from which the defamatory search result were taken were not defamatory in the first place? In the chess player example discussed above, the available information online was only defamatory when it was taken out of context and mischaracterized by the generative AI search engine. Thus, the original speakers—i.e., the sources from which the search engine pulled its information—were neither negligent nor intentionally defamatory in publishing the content. As a result, a defamed plaintiff would be unable to establish the elements of their case against the “original speaker.”

These scenarios further highlight why generative AI search engines don’t fit neatly within the existing Section 230 framework, and the legal principles underlying the statutory framework.

A recent and tragic case out of the Third Circuit Court of Appeals illustrates the serious harm that algorithmically generated content can cause, and the way in which courts are attempting to grapple with the issue of accountability. In Anderson v. TikTok, Inc., at issue was the question of whether TikTok could rely on Section 230 immunity to dismiss a lawsuit brought by the estate of a child who accidentally died while performing a TikTok trend known as the “Blackout Challenge.”[24] Videos depicting the challenge were shown to the child via the TikTok “For You Page” or “FYP”—a feature of the app that relies on algorithmic curation to recommend a “tailored compilation of videos” to the user based on data about their interests and characteristics.[25] The plaintiff argued that TikTok should be held liable for recommending and promoting Blackout Challenge videos to minors’ FYP through its algorithm.[26]

The Third Circuit agreed with the plaintiff, concluding that TikTok’s algorithmic recommendations via the FYP constituted “expressive activity” not immunized under Section 230.[27] The Court explained that because the TikTok algorithm “‘[d]ecid[ed] on the third-party speech that [was] included in or excluded from a compilation—and then organiz[ed] and present[ed] the included items’ on users’ FYPs,” the recommendation was the “first-party speech” of TikTok.[28] Simply put, because TikTok’s algorithm curated an individualized FYP for each user, the platform served not merely as conduit for third-party information, but instead, created unique, expressive content.

Although the case did not involve a generative AI search engine like Google AI Overviews, the Third Circuit’s analysis is instructive as to the way in which courts may apply traditional Section 230 jurisprudence to algorithmically generated content. Indeed, the Third Circuit’s reasoning is easily extendable to the content generated by generative AI search engines that, like the FYP generated by TikTok, curate unique content in response to user activity.

Conclusion

Given its characteristics and capabilities, AI search engines such as Google AI Overviews should be categorized as “material contributors” rather than “neutral tools” under the Section 230 analytical framework. We reach this conclusion given that generative AI search engines actively synthesize information from multiple real-time sources, determine relevance and importance of such information, and generate new content that goes beyond mere aggregation and indifferent publication. Under such circumstances, the technology functions far more like an academic curating and paraphrasing her research findings than a neutral message board or conduit for information. This nuanced characterization may seem slight but could have meaningful implications for both developers of AI technology and those who may be harmed by it.

If the opposite conclusion is reached, and Section 230 immunity applies, those who are harmed by AI-generated search results would be left with little to no recourse. Unlike traditional Section 230 immunity, which leaves the door open for recovery from the original tortious speaker, the potential harm caused by AI search engine results can typically be traced back to only one source—the AI algorithm itself. It’s easy to imagine a world in which Google AI Overviews produces a search result that’s missing context or mischaracterizes the original content in a manner that is either negligent or defamatory. But with Section 230 immunity, AI companies would face no consequences for irresponsible development of their models and injured plaintiffs would have no “original speaker” to blame for their injuries. This lack of accountability could lead to proliferation of misinformation and harmful or defamatory content, as companies prioritize speed and efficiency over safety.

On the other hand, if generative AI search engines aren’t protected under Section 230, the AI ecosystem may become more restrained. It’s important to remember that the primary motivation behind the passage of Section 230 was to “preserve the vibrant and competitive free market that presently exists for the Internet”—i.e., to ensure that innovation would not be stifled by the fear of liability.[29] These principles are equally, if not more applicable, in the context of AI. AI companies might feel pressured to rein in their advancements to avoid content creator liability while the ongoing AI arms race incentivizes them to push those boundaries.

The tension between innovation and legal liability is exacerbated by the absence of comprehensive AI regulation clearly defining the contours and applicability of Section 230 immunity in the context of generative AI. This dearth of regulation may remain the status quo for the foreseeable future, as congressional attempts to regulate AI have largely fallen flat in recent years. There have been two notable, but unsuccessful, efforts to address the issue posed by generative AI with regard to Section 230 immunity. In March 2023, Senator Marco Rubio introduced legislation to amend Section 230.[30] The proposed legislation would classify platforms that amplify information using an algorithm as “content providers” with respect to the information they promulgate via AI. This amendment would impose liability on those platforms for the content amplified algorithmically or by some other automated processes. In June 2023, Senator Josh Hawley introduced a bill that would waive immunity under Section 230 for claims and charges related to generative artificial intelligence, which was defined to mean “an artificial intelligence system that is capable of generating novel text, video, images, audio, and other media based on prompts or other forms of data provided by a person.”[31] Both bills died in the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation. And although the Biden administration issued an executive order addressing the federal regulation of AI, the action did nothing to answer the question of whether Section 230 immunity should be applied to content generated by AI.[32]

Given these circumstances, it seems likely that courts, rather than legislators, will take the lead in defining the limits of Section 230’s applicability to generative AI technology. Leaving such a complex task to judges and lawyers—most of whom are likely not technological experts in artificial intelligence—may lead to unpredictable, undesirable, and inconsistent results. For example, while the Third Circuit may view algorithmic curation as “expressive activity,” courts in other parts of the country may adopt a different approach, resulting in a patchwork of protection for those harmed by tortious content generated and promulgated by artificial intelligence.

Generative AI search engines highlight the need for a more nuanced approach to online content regulation in a world where generative AI exists. These tools challenge our traditional understanding of content creation and distribution, with their ability to synthesize and generate novel content from multiple sources under the guise of unlimited information access and apparent expertise. Without appropriate legislation or regulation that balances innovation and liability, we risk creating an AI landscape that neither companies nor individuals can navigate safely or effectively.

47 U.S.C. § 230. ↑

Liz Reid, “Generative AI in Search: Let Google Do the Searching for You,” The Keyword (blog), Google, May 14, 2024. ↑

“SearchGPT Prototype,” OpenAI, July 25, 2024. ↑

“What Is a Lawyer?,” Division for Public Education, American Bar Association, September 10, 2019. ↑

Nico Grant, “Google Rolls Back A.I. Search Feature After Flubs and Flaws,” New York Times, June 1, 2024. ↑

Rory Carroll, “Google’s AI Search Is Telling Car Drivers to Consider Changing Their Blinker Fluid,” Quartz, May 20, 2024. ↑

Matteo Wong, “Google Is Turning Into a Libel Machine,” The Atlantic, June 21, 2024. ↑

Id. ↑

Goddard v. Google, Inc., 640 F.Supp.2d 1193,1196 (N.D. Cal. 2009) (under Section 230, a website will be liable only if it “contribute[s] materially” to the alleged unlawfulness, not when it “merely provides third parties with neutral tools to create web content”); Fair Housing Council of San Fernando Valley v. Roommates.com, LLC, 521 F.3d 1157, 1172 (9th Cir. 2008) (explaining that Section 230 immunity applies when “the website operator [is] merely a passive conduit” for the publication of the allegedly defamatory content). ↑

Goddard, 640 F.Supp.2d at 1196. ↑

992 F.Supp. 44 (D.D.C. 1998). ↑

Id. at 49. ↑

Fair Housing Council at 1172. ↑

Id. at 1169. ↑

Id. ↑

831 F.3d 352 (6th Cir. 2016). ↑

Id. at 355. ↑

Id. ↑

Toby Walsh, “Eat a Rock a Day, Put Glue on Your Pizza: How Google’s AI Is Losing Touch with Reality,” The Conversation, May 27, 2024. ↑

“Geologists Recommend Eating At Least One Small Rock per Day,” ResFrac Corporation, May 19, 2021, updated May 2024. ↑

“Geologists Recommend Eating At Least One Small Rock per Day,” The Onion, April 13, 2021. ↑

Zeran v. America Online, Inc., 129 F.3d 327, 330 (4th Cir. 1997). ↑

See Restatement (Second) of Torts § 558 (Am. Law Inst. 1977). ↑

116 F.4th 180 (3d Cir. 2024). According to the Court’s opinion, the “Blackout Challenge” encouraged users “to choke themselves with belts, purse strings, or anything similar until passing out.” Id. at 182. ↑

Id. at 182. ↑

Id. ↑

Id. at 184. ↑

Id. ↑

Bennett v. Google, LLC, 882 F.3d 1163, 1165 (D.D.C. 2018) (quoting 47 U.S.C. § 230(b)). ↑

Disincentivizing Internet Service Censorship of Online Users and Restrictions on Speech and Expression Act (“DISCOURSE Act”), S. 921, 118th Cong. (2023–2024). ↑

A bill to waive immunity under section 230 of the Communications Act of 1934 for claims and charges related to generative artificial intelligence, S. 1993, 118th Cong. (2023–2024). ↑

“Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence,” Exec. Order. No. 14110, 88 Fed. Reg. 75191 (Oct. 30, 2023). ↑