Since the new Hart-Scott-Rodino (“HSR”) Rule was finalized in October 2024, there have been dozens of articles summarizing the changes and new requirements. While these articles are helpful and understanding the changes is necessary, for in-house counsel some of the logistical challenges presented by the new HSR regime are as important as the legal ones. This article’s goal is to identify practical solutions for the efficient and compliant collection, review, and production of some of the new categories of documents and information required by the HSR changes.[1]

The changes discussed below fall into two categories: deal-agnostic changes (i.e., those that apply to every deal) and deal-specific changes (i.e., those that only apply when there is an overlapping product or service between the parties).

Deal-agnostic changes include the requirements to provide certain

- final documents sent to or from the supervisory deal team lead and

- draft documents that are sent to any board member.

Deal-specific changes include the requirements to provide

- regularly prepared CEO reports containing relevant information,

- board reports containing relevant information,

- information about overlapping directorates,

- detailed customer information, and

- detailed supply relationships information.

Deal-Agnostic Changes

Previously, only “Competition Documents”[2] sent to a director or officer had to be produced with an HSR filing. The new HSR Rule changes that in two significant ways: (1) all final Competition Documents sent to or from the supervisory deal team lead (“SDTL”) are producible, and (2) draft Competition Documents sent to any individual board member are producible.

Final Competition Documents Sent to SDTL

As an initial matter, in-house counsel will want to carefully consider whom to designate as the SDTL for a deal (or for all deals). The new rule defines supervisory deal team lead as “the individual who has primary responsibility for supervising the strategic assessment of the deal, and who would not otherwise qualify as a director or officer.”[3] The rule appears to envision the SDTL as the person who makes the yes/no call on whether to send the deal to the board (or similar entity) for final approval. In some companies, this may also be the person overseeing the deal on a day-to-day basis. As you move into larger companies with more complex corporate development teams, those roles may be separated. For companies that do not have dedicated corporate development teams, potential SDTLs could include a business stakeholder assessing whether the target would be a strategic fit or someone in the Finance Department.

After identifying the SDTL, in-house counsel should orient that person to the new requirements immediately, and together they should design a workable process for collecting and reviewing relevant documents. The goal, of course, is not to significantly disrupt the ongoing work evaluating strategic acquisitions. Some useful practices include the following:

Create a deal-specific mailbox, and put all emails relating to the deal in that mailbox. This will reduce the need for email searches, and the SDTL can simply provide antitrust counsel access to the mailbox so that the SDTL will not have to waste time or energy assessing what is producible.

Inform the SDTL that documents accessed through collaborative platforms/channels will be produced. All final Competition Documents, including communications, housed in collaborative platforms/channels such as Teams, Slack, Google Chat, etc., likely must be produced if accessed by the SDTL. In-house counsel should introduce the SDTL to this requirement proactively so the SDTL can be mindful regarding if and how to use such channels throughout the deal.

Communicate to deal stakeholders that emails sent to the SDTL will be produced. All final Competition Documents sent from or received by the SDTL must be produced. It is therefore important that in-house counsel inform all deal stakeholders of this requirement and remind them to be thoughtful in their email practices. This may include reminders to always use accurate language in emails, to not speculate, and to avoid unnecessarily cc’ing the SDTL on every correspondence.

Separate substantive discussions from drafting discussions in emails. All final Competition Documents sent to the SDTL must be produced. As a general matter, the new rule defines a final document to include an email. An important exception is that emails discussing draft documents are not considered final. For example, an email identifying and explaining the redline edits made in a document is considered a draft and not producible. However, an email that explains redline edits and discusses the competitive dynamics of the deal is likely producible. Separating drafting emails from substantive discussions will avoid this confusion.

These processes and practices work best in conjunction. But even implementing one or two of these practices will make life easier for both the SDTL and in-house counsel.

Draft Competition Documents Sent to Any Single Board Member

Previously, draft Competition Documents were only producible if they went to the entire Board of Directors or subcommittee thereof. Under the new rule, a draft Competition Document is producible if it is sent to any individual member of the board.

In-house counsel will therefore want to investigate the processes the corporate development team uses for document creation to determine if individual board members ever receive documents outside of official channels. For example, does a senior member of the corporate development team bounce ideas off an individual board member before finalizing a document to send to the whole board? To the extent that any such processes exist, in-house counsel will want to inform all stakeholders that these types of draft documents must now be produced to regulators. Similarly, if board members have a day-to-day role on a transaction and are expected to receive documents outside their role, this should also be flagged to help inform production decisions.

Deal-Specific Changes

Many of the changes in the new HSR Rule only apply when there is a competitive overlap between the acquirer and the target. These deal-specific requirements are sufficiently numerous that it is fair to say there are effectively now two different HSR forms: one for deals with overlaps and one for deals without them. Because the HSR submission for deals with overlaps is considerably more onerous, parties should now make the overlap assessment much earlier in the deal process—indeed, it will be difficult to accurately gauge either the timeline or budget for an HSR filing without first making this determination.

After concluding the deal involves an overlap, in-house counsel must begin the process of collecting new categories of information and documents. This section addresses five of the most burdensome and/or tricky of those categories:

- Regularly prepared CEO reports that contain information on the competitive dynamics of the overlapping product market or service line

- Board reports that contain information on the competitive dynamics of the overlapping product market or service line

- Information on individual board members who also serve on the boards of other companies that operate in the same industry

- Detailed information about each party’s customers of the overlapping product market or service line

- Detailed information about the parties’ supply relationships with regard to the overlapping product market or service line

Regularly Prepared CEO Reports Discussing Competition in the Overlapping Market

The new rule requires parties to produce regularly prepared CEO reports if they (1) discuss competition-related issues involving the overlapping market implicated by the deal and (2) were prepared within one year of filing. Regularly prepared reports are specifically defined as quarterly, biannual, or annual reports. The challenge, therefore, is determining when a report contains information making it responsive, which is amplified by the one-year lookback window. It will not usually be apparent when the report is prepared whether it will be responsive later. The following processes may help mitigate these challenges:

Work with the CEO’s staff ahead of time to understand the full universe of regularly prepared reports the CEO receives, and inform the CEO of the need to collect these documents. The CEO undoubtedly receives reports that do not contain producible information, e.g., a report outlining insurer and benefits administrator options for employees. The CEO is also likely to receive reports that contain information on the competitive dynamics of markets. Understanding ahead of time the full corpus of regularly prepared reports that the CEO receives—and the content of those reports—will allow in-house counsel to more efficiently allocate their attention when reviewing materials for responsiveness for a specific deal.

Determine whether a preemptive review of the regularly prepared CEO reports is necessary. As discussed, it will not be clear in real time whether a CEO report will have to be produced. And parties cannot extract only the responsive information/pages from a report. Thus, in-house counsel should assess whether there are ways to balance the HSR requirements against the burden of producing nonresponsive information. To use the prior example, simply issuing two different reports—one on benefits and one on competitive dynamics—will prevent the company from having to produce totally irrelevant (but highly sensitive) benefits information because it is included in a competitive intelligence overview.

Determine who will review the CEO reports, and train that person. Regardless of whether there is a preemptive review, in-house counsel will have to work with the CEO’s staff to determine who should review the CEO reports when you must file an HSR form. Ideally, this would be in-house or external antitrust counsel. However, given the highly sensitive nature of the reports, the CEO’s office may prefer someone else. This may be a senior staff member, the general counsel, or other trusted adviser. In any event, it will be in-house counsel’s responsibility to thoroughly train the reviewer so that the reviewer can identify the types of competitive information that make a report responsive. This training should include clear instructions to err on the side of flagging for production, and if a nonlawyer conducts the preliminary review, it will have to be confirmed by counsel before filing.

Keep a checklist of regularly prepared reports, and check it before filing. Failing to include a producible document in an HSR filing may lead to, at a minimum, a costly delay in closing. This type of mistake can be avoided by creating and maintaining an up-to-date list of all quarterly, biannual, and annual reports the CEO receives and then checking off each one during the review process.

Organize all regularly prepared CEO reports in real time. The easiest way to miss a CEO report (especially without a checklist) is to scramble to collect them every time you file an HSR form. Even with the soundest of efforts and intentions, if in-house counsel are furiously searching inboxes, platforms, and other storage solutions on an ad hoc basis for each deal, eventually something will be missed. Instead, in-house counsel should work with the CEO’s staff to create separate folders for quarterly, biannual, and annual reports and ensure they are updated in real time. In addition to reducing the risk of missing a report, this will save both in-house counsel and the CEO’s office time when a filing is required by eliminating the need for last-minute searches.

Any Board Report Discussing Competition in the Overlapping Market

The new HSR Rule imposes the same requirements on board reports as CEO reports, with one notable expansion: instead of only requiring regularly prepared reports, the rule requires production of any board report discussing competition in the overlapping market. This requirement also has a one-year lookback window, so companies will not know at the time a board report is created whether it is producible.

The challenges presented by this requirement are akin to CEO reports but may be amplified if processes are not followed because the requirement is not limited to regularly prepared reports. Fortunately, implementing the same process for board reports as for CEO reports may reduce both burden and risk:

- Work early with whoever prepares board materials to understand the full universe, and introduce that person to the new requirements.

- Determine whether a preemptive review will occur and, if so, who will conduct it.

- Determine who will review board reports when an HSR filing is required.

- Train the reviewers if they are not dedicated antitrust counsel.

- Organize board files in an easily accessible and navigable manner in real time.

- Conduct periodic audits of the board’s documentation to ensure compliance with the new rule and identify any gaps.

There are two additional practices that may help with collecting and reviewing board reports and minimize the risk of missing a responsive document:

Consolidate board reports. If one hundred reports are sent to the board every year, it will be exponentially easier to collect and review those reports if twenty-five are bundled at the end of every quarter than if they are sent individually on an ad hoc basis. And although the requirement still applies that if any part of a report is responsive the whole report must be produced, administratively bundling twenty-five independent reports into a zip drive does not magically transform them into one report for HSR purposes. There is, therefore, little downside and significant upside to sending board reports in a routine, standardized, and consolidated manner.

Organize the board’s documents in a workstream or platform. Rather than sending board reports, upload them to a specified platform or portal, ideally at a specific, standard time such as before meetings. Do not send any board reports to the board (or individual members) outside of this platform. If the only way the board can access its reports is by logging onto the platform, in-house counsel can be assured of a single, easily accessible source of truth when an HSR filing occurs.

Providing Information About Overlapping Directorates

Another new category of information required by the new HSR Rule relates to overlapping directorates. Specifically, the acquirer must determine if any of its board members serve on the board of a different company (i.e., not the target) that reports revenue in the same North American Industry Classification System (“NAICS”) codes as the target. For example, if Company A provides cybersecurity services and is acquiring Company B, which provides software, in-house counsel for Company A will have to determine whether any members of its board also sit on the board of any other company that provides software. If so, Company A must disclose the name of the director(s) and the other board(s) on which they sit as part of the HSR filing. Several processes can help with collecting and producing this information:

Implement policies to review board affiliation. There are good legal reasons—beyond just HSR requirements—to enact policies that review not only the number of external board affiliations each director can have but also the types of companies with which they may be affiliated. To explain why, it may be helpful to take a step back.

Many acquirers target companies that operate in the same industry/ecosystem. These companies are likely to report revenues in a limited number of NAICS codes relevant to that ecosystem. Conversely, it is less common for an acquirer to target a company in an unaffiliated industry. Companies in unaffiliated industries are unlikely to report revenues in NAICS codes common to the ecosystem. Accordingly, the more directors a company has who sit on the board of other ecosystem companies, the more likely any individual target hits on a NAICS code that requires disclosure. One way to minimize the need to identify overlapping directors is to enact a policy that curtails the number of board members who can join other for-profit boards in the same ecosystem.

Even outside of HSR, Section 8 of the Clayton Act prohibits directors from sitting on the boards of competing companies. Therefore, having policies in place that prevent overlapping directorates and having mechanisms in place to monitor and track external board membership to ensure compliance serve two goals.

Monitor board memberships in real time. Because NAICS codes can be defined so broadly, some degree of disclosure is likely inevitable even with the above policy. Absent proactive processes, this could impose a substantial burden on in-house counsel and delay the HSR filing (and, consequently, the closing). Imagine having a large board of twenty directors. If board affiliation information is not already available, in-house counsel will first have to determine whether any of the twenty directors are on other for-profit boards, and which ones. If, for example, each is on two additional boards, in-house counsel will then have to research the products and services that all forty of those companies offer and compare them to the target.

To prevent this, the overlapping directorate assessment should be part of the real-time approval process, both for any new member of the company’s board and for any existing member who wants to join an external board. If the company is considering adding someone to the board, in-house counsel should review the candidate’s current board and officer affiliations to determine whether any are with competitors or ecosystem players. Again, this will also help ensure compliance with Section 8. In-house counsel can track this analysis in real time so that when they make an HSR filing, they not only will have a current list of all directors and corresponding affiliations but also will already have done some of the industry analysis.

Customer Information for Overlapping Products/Services

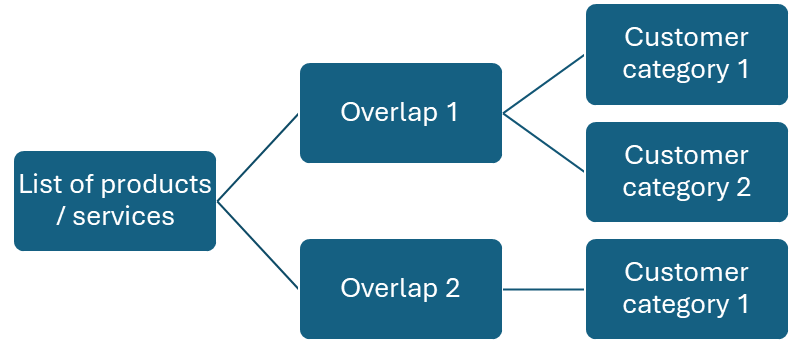

In all deals, both parties now must describe the categories of products and services they offer. Where there is a current or planned overlap, the parties must provide (1) total revenue for each overlapping product/service from the prior fiscal year, (2) the top ten customers by category for each overlapping product/service, and (3) the top ten overall customers for each overlapping product/service.

Figure 1. Customers by Category. See note 4 for a discussion of this chart’s example.

The time needed to respond to this requirement will largely depend on the number of “customer categories” involved[4] and the extent to which in-house counsel have proactively developed processes to collect this information.

The term customer categories is not defined in the rule or guidelines. Unfortunately, neither the rule nor any guidelines published thus far define what customer category means in this context. Some possibilities include categories by industry; by distribution level (retailers, wholesalers, distributors, direct to consumer, etc.); and by geography (local customers, regional customers, national customers, international customers, etc.). Therefore, it will likely be up to in-house counsel to make this determination.

There are various approaches companies can take to define customer categories. As a first step, in-house counsel should consult with business stakeholders in the overlapping products/services to determine whether there is an internal ordinary-course definition of customer categories. If the company has a preestablished definition, in-house counsel should likely use that. If not, in-house counsel may have to look to other sources in defining customer categories for HSR purposes, such as the business’s informal understanding (“we tend to view customers this way”) or external industry standards.

Proactively socialize stakeholders in financial roles, including understanding how these requirements do (or do not) comport with how revenue is tracked in the ordinary course. In-house counsel will likely depend on Finance to collect the above information, so, as with other stakeholders, they will want to orient Finance to these changes beforehand. In particular, in-house counsel will want to determine how long it will take Finance to pull these reports, which is largely a function of whether it tracks revenue data in the manner specified by the reporting requirements. For example, Finance may not track customers “by category,” much less track the top customers in each (nonexistent) category. In this example, Finance would not be pulling a report but creating one, which could take significantly longer. Knowing this at the outset will help in-house counsel manage expectations.

Supply Relationships Information for Overlapping Products/Services

The new HSR Rule requires both parties to identify (1) any products or services it sells to or purchases from the other party and (2) any products or services it sells to or purchases from competitors of the other party.[5] For each such input, the parties must provide detailed sales information and a list of the top ten customers that use each party’s products as an input to compete with the other party. Identifying supply overlaps and producing the requisite information may be particularly laborious. In addition to socializing Finance stakeholders to this requirement (see above), the following actions may help with this task:

Enlist the help of those performing due diligence on the acquisition to help identify overlaps. Unlike with competitive overlaps, it may not be apparent whether the parties have any type of vertical relationship with each other, much less with one of the other party’s competitors. However, the due diligence team should already be reviewing supply relationships/contracts in strategically assessing and valuing the deal. In-house counsel may be able to leverage that work so due diligence can flag any relevant supply relationships in real time.

Use a reasonable definition of input. The new rule requires the above information when either party (1) purchases from or supplies to the other party an input or (2) purchases from or supplies to the other party’s competitors an input that helps them compete. Although in-house counsel will want to err on the side of caution in determining which inputs qualify for the latter, overhead products and services that every company uses likely would not count. Imagine the acquirer is a children’s toy manufacturer and purchases plastic from the target’s competitor for use in its products—that would qualify. Imagine now that the target’s competitor also manufactures and sells bottled water that the acquirer purchases and stocks in its offices. Although this is a “product” supplied by the target’s competitor to the acquirer, it would likely fall outside the scope of this requirement because it is unrelated to competition in the toy manufacturing market. Again, in-house counsel should not take an overly restrictive approach but instead take a good-faith, commonsense approach using their professional judgment, which recognizes that some inputs (food, water, electricity, basic equipment, structures, etc.) are so weakly connected to competition (unless the acquirer operates in that industry) that they are not meant to be subject to this requirement.

Conclusion

The new HSR Rule will add time and expense to filings. However, it will impact deals with overlaps significantly more than deals without overlaps. As a result, in-house counsel must endeavor to make the overlap determination much earlier than under the old regime so they can start the collection-and-review process early and accurately set budget and timing expectations.

Regardless, the amount of additional time and burden the new HSR Rule imposes will be proportional to the number of processes, practices, and socializations in place at the time of filing. The way in-house counsel can most effectively support the business’s acquisition strategy, therefore, is by proactively enacting processes that minimize cost, time, and disruption when an HSR filing is required.

Matt Bester and Paul Covaleski talk about their tips on Our Curious Amalgam, the podcast of the ABA Antitrust Law Section. Listen to Episode #320, “What Can In-House Counsel Do To Tame the Premerger Notification Beast? Practical Suggestions For Complying With the New HSR Rules” (April 7, 2025), available at www.ourcuriousamalgam.com.

As the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) releases additional guidance on the new HSR form, some of the below practices may have to be altered, eliminated, or expanded upon. In-house counsel will therefore want to track any such guidance closely and adjust their practices accordingly. ↑

The new HSR Rule also changed the nomenclature: documents previously referred to as 4(c) documents are now referred to as Competition Documents, while documents previously referred to as 4(d) documents are now referred to as Transaction-Related Documents. For the sake of clarity, and because it is not relevant here, this article refers to all items previously referred to as 4(c) or 4(d) documents as Competition Documents. ↑

Premerger Notification; Reporting and Waiting Period Requirements, 89 Fed. Reg. 89,216, 89,279 (Nov. 12, 2024) (emphasis added). ↑

In the chart above, the company would have to disclose thirty customers to comply with this requirement: twenty for overlap 1 because there are two categories of customers, and ten for overlap 2 because there is one category of customer. This illustrates how the definition of customer category will directly and substantially impact the burden associated with this requirement—if each overlap had ten customer categories, the company would have to disclose two hundred customers. ↑

The rule contains an exception for inputs with less than $10 million in sales. ↑