Introduction

Congress should repeal or modify section 16(b) (Section 16(b)) of the Securities Exchange Act (Exchange Act) of 1934.[1] This provision requires certain corporate “insiders” to disgorge profits that they earn from “short swing” transactions in the stock of public companies. Section 16(b) defines a purchase and sale, or sale and purchase, within six months’ time as a short-swing transaction. Congress included the provision as part of the original Exchange Act in an effort to discourage insider trading.

A fair reading of Section 16(b) leads to the conclusion that this provision: (1) never achieved its original purpose; (2) creates a trap for unwary; and (3) needlessly complicates ordinary business transactions. Furthermore, other provisions of the Exchange Act and attendant rules more effectively prohibit the activity that the framers of Section 16(b) sought to stop. The Department of Justice and the Securities and Exchange Commission (the SEC or Commission) use other prohibitions, some of which the SEC and the courts developed later, against insider trading and market manipulation.

Section 16(b) was just one of a multitude of provisions that Congress enacted in 1934 with the hope of cleaning up Wall Street. Faced with 85 years of evidence, it is time to recognize that Section 16(b) was a mistake and that keeping it on the books causes much more harm than good. I explain my reasoning below.[2]

Congress’s Enactment of Section 16(b)

Section 16(b) of the Exchange Act provides that an officer, director, or 10-percent beneficial owner of any equity security that is registered pursuant to section 12 of the Exchange Act (a covered person) must disgorge any profit that he or she derives from the sale and purchase, or purchase and sale, of any equity security of such issuer within any period of less than six months. The provision creates a private right of action for the issuer to recover the profit from a covered person and allows the owner of any security to sue on behalf of the issuer. Congress stated that the purpose of the provision was to prevent the unfair use of information to which such covered persons might have access. Congress created a strict liability provision, i.e., covered persons are liable irrespective of any intention that they may have had.[3]

Section 16(b) is unique in at least two respects. It does not authorize the SEC to bring an action against insiders who trade within the six-month period. Instead, it provides that the issuer may bring an action to recover the profit, and if the issuer declines to do so, that the shareholder may bring such an action.[4] The U.S. Supreme Court noted that “Congress clearly intended to put ‘a private-profit motive behind the uncovering of this kind of leakage of information, [by making] the stockholders [its] policemen.’”[5] Although Section 16(b) provides that the profits belong to the issuer, the attorneys who bring cases for shareholders obtain attorney’s fees for their efforts.[6]

Congress’s inclusion of Section 16 was no accident. The Pecora Report[7] outlines a litany of shameful practices in which officers, directors, large shareholders, specialists, and others engaged. These activities manipulated markets, penalized public shareholders, and earned such insiders large profits. The Pecora report notes in part:

Among the most vicious practices unearthed at the hearings before the subcommittee was the flagrant betrayal of their fiduciary duties by directors and officers of corporations who used their positions of trust and the confidential information which came to them in such position, to aid them in their market activities. Closely allied to this type of abuse was the unscrupulous employment of inside information by large stockholders who, while not directors and officers, exercised sufficient control over the destinies of their companies to enable them to acquire and profit by information not available to others.[8]

***

(e) Regulation of market activities of officers, directors, and principal stockholders.—The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 aims to protect the interests of the public against the predatory operations of directors, officers, and principal stockholders of corporations by preventing them from speculating in the stock of the corporations to which they owe a fiduciary duty. Every person who is the beneficial owner of more than 10 percent of any class of equity security registered on an exchange or who is a director or officer of the of issuer such security must report to the Commission whenever any change occurs in his ownership of stock in the corporation. In the event that he realizes any profits from the purchase and sale or, sale and purchase of an equity security within period of less than 6 months, he is bound to account to the corporation for such profits. It is also made unlawful for insiders to sell the security of their corporations short or to make “sales against the box.” By this section, it is rendered unlawful for persons intrusted [sic] with the administration of corporate affairs vested with substantial control over corporations to use inside information for their own advantage.[9]

The SEC Historical Society explains:[10]

In a 1965 interview, Ferdinand Pecora recalled how he, [Thomas] Corcoran, James Landis and Benjamin Cohen had drafted Section 16 as “the anti-Wiggin section,” named after Albert H. Wiggin, who headed the Chase Manhattan Bank from 1921 to 1933. Pecora recalled how Wiggin had testified that he short-sold Chase National Bank stock that he didn’t own but expected to repurchase at a lower price, and thereby took a profit through six different private investment corporations he had established. One of them had taken a profitable position with Sinclair Oil and Refining Company at a time when Sinclair had a large line of credit with Chase Bank. The securities trading abuses of such people, said Pecora, “were the reason that we drafted [Section 16] of the Act, as we burnt the midnight oil.”

The SEC clearly liked Section 16(b). A 1941 SEC report reads:

Section 16(b) of the act recognizes that profits realized by officers, directors, or 10-percent stockholders from any purchase and sale or any sale and purchase of any equity security within a period of 6 months rightfully belong to the corporation and should be recoverable in an action by, or on behalf of, the corporation. Representatives of the securities industry propose that section 16(b) be repealed. The Commission is unalterably opposed to this suggestion, since it would strip investors of one of their most essential protections.

It has been asserted that the provision operated to deter insiders from making purchases to retard a falling market. But if an insider really wishes to cushion a decline, section 16(b) does not make it unlawful for him to do so. It is only where the insider makes a profit within the relatively short period of 6 months that his profit is required to be turned over to the corporations. Furthermore, that particular argument for repeal of section 16(b) presupposes that insiders would act to bolster the market by trading primarily against the trend, buying in weak markets and selling in strong markets. But, even if it be assumed that some corporate officials would so act, the mere fact that the activities of some trustees might be advantageous to their beneficiaries has never been considered an adequate reason for an abolition of the prohibition against self-dealing by trustees in trust property.

Moreover, even if insiders would purchase in order to bolster the market, there is serious doubt whether investors would always be benefited. If the market continued to fall after the insiders had attempted to support the market, their activities would have injured those new investors who had been induced not to sell and those new investors who had been induced to purchase by the false appearance of stability thus created.

It has been argued that section 16(b) applies in some instance to profits even though made without the use of inside information. This argument is clearly beside the point. The mere existence of temptation on the part of fiduciaries to abuse their position had traditionally led the courts to bar them from activities in fields where such temptations exist. Thus, where trustees acting in their own interest with trust assets, it has long been settled that they will be required to account for any personal profits made regardless of whether they take advantage of their position and regardless of whether the beneficiaries suffered. Similarly, a corporate officer may not acquire for himself an opportunity which is available to his corporation even though it cannot be demonstrated that the corporation has been damaged by the acquisition. And this is true even where the corporation has not had the financial resources to avail itself of the opportunity. The deterrent of section 16(b) to in-and-out trading by insiders is thus consistent with the time-honored doctrine that a trustee must avoid any activity which involves even a remote possibility of a conflict of interest between his fiduciary obligation and his personal self-interests. The Commission is convinced that any legislation which sought to distinguish between situations where inside information is actually used and those where it is not used would be self-defeating because of the inherent difficulties of establishing the use of inside information in particular cases.[11]

It may also be urged with much force that even to the extent that section 16(b) may permit the recovery of profits made without the use of inside information it achieves a highly desirable objective. It is to be doubted whether the interests of security holders are benefited when the attention of their officers and directors is diverted from the corporation’s affairs to stock market speculation in its securities.[12]

Representatives of the securities industry couple their proposal to repeal section 16(b) with a suggestion that section 16(a) require that insiders, instead of reporting their transactions monthly, do so within 10 days after becoming offices, directors, or 10-percent stockholders. They assert that the publicity provisions of section 16(a) as thus amended would be adequate to prevent abuses. Although the reporting of transactions may in some cases operate as a deterrent, it cannot be expected to prevent insiders from taking advantage of inside information. The temptations and the potential returns are too great to be effectively overcome merely by subsequent publicity. It was because the Congress did not believe that publicity alone would be sufficient that it defined the standard in section 16(b)—that insiders, because of their fiduciary relationship, should not trade in-and-out in the securities of their companies for personal gain. The consequences of failing to comply with this standard are not penal. The section does not make insiders’ trading unlawful; it does not even subject insiders to injunctive proceedings. It simply guards against the use of inside information since such information is not the personal property of the insiders themselves and since any profits resulting from its use belong to the insides no more than does the insider information itself.[13]

What Law Makes Insider Trading Unlawful?

Section 16(b) is not an effective tool for policing insider trading. Section 16(b) does not make it unlawful for insiders to trade; it simply requires them to disgorge the profit. It does not grant the SEC or any other government body authority to enforce its prohibitions. By comparison, Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act and Rule 10b-5 allow U.S. attorneys to prosecute wrongdoers criminally and allow the SEC to bring civil enforcement actions against malefactors.

The U.S. government’s efforts to prosecute insider trading has taken a very different path. The Commission adopted Rule 10b-5 in 1942, i.e., after Congress enacted Section 16(b).[15] The history of SEC enforcement for insider trading began in 1961. The SEC brought an administrative action for insider trading, relying on Section 17(a) of the Securities Act of 1933 and Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act and Rule 10b-5 thereunder. In In the Matter of Cady, Roberts & Co., the SEC concluded that when a board member of a public company tipped a registered representative of a broker-dealer about the issuer’s plan to reduce its dividend, and the representative sold the issuer’s securities, the representative violated Rule 10b-5 and Section 17 of the Securities Act of 1933.[16]

Since that early case, the law of insider trading has evolved. Congress, the U.S. Supreme Court, and the SEC all have ensured that Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 now constitute strong weapons against insider trading. For example, Congress enacted the Insider Trading Sanctions Act in 1984, which authorizes the SEC to bring a court action seeking a civil penalty of up to three times the wrongdoers’ profits.[17] The Insider Trading and Securities Fraud Enforcement Act of 1988 (ITSFEA), among other measures, expanded controlling personal liability for insider trading and required broker-dealers and investment advisers to have surveillance systems reasonably designed to prevent insider trading.[18] In 2016, a unanimous U.S. Supreme Court upheld criminal convictions for insider trading under Section10(b) of the Exchange Act and Rule 10b-5. The court unanimously reaffirmed its view of the law that it first had articulated in 1983.[19] In addition to Rule 10b-5, the SEC adopted Rule 14e-3 to outlaw insider trading in connection with a tender offer.[20] Prosecutors often also charge defendants with violating federal mail and wire fraud statutes because those statutes may have lower burdens of proof.[21] In summary, presumptive insider trading under Section 16(b) buys you an expensive lawsuit; actual insider trading under Rule 10b-5 lands you in jail.[22]

Section 16(b) in Practice

If Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 are the meaningful insider trading prohibitions, what harm is there in keeping Section 16(b)? Isn’t it better to be safe than sorry? Even a cursory examination of the practical effects of Section 16(b) should lead an honest observer to question the utility of the provision.[23] Section 16(b) has spawned countless interpretive questions, such as who is an officer, who is a “real” versus an honorary director, and how one must calculate 10-percent ownership. The SEC has adopted rules to clarify many aspects of Section 16(b), but for reasons discussed below, all of this complexity has not made the securities markets more honest for investors.

1. Does Not Deter Insider Trading Effectively

Congress assumed that a covered person trading within six months must “know something” that other investors or the public does not, regardless of what the insider actually knows. Section 16(b) does not prohibit insider trading; it merely seeks to remove its profitability.[24] Accordingly, Section 16(b) imposes liability regardless of whether the covered person actually traded on inside information. As a strict liability provision, it imposes liability even if the insider:

- did not know of the existence of Section 16(b);

- received inaccurate legal advice about the provision;

- miscalculated the six-month period;

- mistakenly assumed that the restriction did not apply to transactions with other insiders;[25]; or

- rescinded a trade to avoid liability.[26]

These are just a few examples of when Section 16(b) imposes liability under circumstances that do not further its policy objective. Romeo & Dye note that Section 16(b) does not impose liability on many situations that do constitute insider trading. For example, Section 16(b) does not apply to:

- all persons who might have actual access to, and while in possession of, inside information;

- tippers or tippees; or

- insider trading that occurred after six months.[27]

In short, Section 16(b) does not deter insider trading because it is both over- and under-inclusive.[28] Many observers have called it a “trap for the unwary.”[29]

I have summarized below some of the perverse outcomes that Section 16(b) has created. It is just a sampling of the problems that Romeo & Dye and others have described.

2. Damage Calculation May Be Unfair

The courts have developed a methodology for calculating profitability on Section 16(b) that is needlessly punitive. “Operating on the premise that Congress intended Section 16(b) to have the maximum deterrent effect, the first appellate court to decide a Section 16(b) case stated that ‘[t]he only rule whereby all possible profits can be surely recovered is that of lowest price in, highest price out.’’’[30] The Commission noted that “under this method, profit is computed by matching the highest sale price with the lowest purchase price within six months, the next highest sale price with the next lowest purchase price within six months, and so on, until all shares have been included in the computation.”[31] The net result of this methodology is that a covered person who violates Section 16(b) may have to pay illusory profits to the plaintiff, notwithstanding that the covered person will have lost money under any conventional calculation of gain or loss.[32]

3. Fiduciary Theory—Not Sensible in This Context

As the preamble to Section 16(b) notes,[33] Congress enacted the prohibition “[f]or the purpose of preventing the unfair use of information which may have been obtained by such beneficial owner, director, or officer by reason of his relationship to the issuer. . . .” As noted above, the Pecora report expressed the view that officers, directors, and ten-percent shareholders should not take advantage of their position in the corporation for personal profit. The 1941 SEC Report suggests that any such profit rightfully belongs to the issuer.

Of course, it is unethical, and should be illegal, for corporate insiders to benefit from such inside information. However, I disagree with the notion that such a profit rightfully belongs to the issuer. Section 16(b) claims to reflect principles of fiduciary law, including the idea that a covered person should not benefit personally from his or her position of trust. A covered person who engages in a short-swing transaction is not usurping a corporate opportunity. For example, I appreciate that an officer should not secretly buy a tract of land in which the issuer is interested, and then raise the price of the land in a subsequent sale to issuer, but an issuer should not trade its own securities without making proper public disclosure to the markets. Doing so would violate Section 10(b) and Rule10b-5 and perhaps other Exchange Act provisions.

SEC Rule 10b-18 provides a safe harbor for issuers that repurchase their shares. The Division of Trading & Markets Frequently Asked Question notes:

Question 1: If an issuer executes purchases that are in technical compliance with the safe harbor conditions, will that protect the issuer from all liability for such purchases?

Answer: No. Some issuer repurchase activity that meets the safe harbor conditions may still violate the anti-fraud and anti-manipulation provisions of the Exchange Act. For example, Rule 10b-18 confers no immunity from possible Rule 10b-5 liability where the issuer engages in the repurchases while in possession of material, non-public information concerning its securities, or where purchases are part of a plan or scheme to evade the federal securities laws. Therefore, regardless of whether an issuer’s repurchases technically satisfy the conditions of Rule 10b-18, the safe harbor would not be available if the repurchases are fraudulent or manipulative, when all the facts and circumstances surrounding the repurchases are considered (i.e., facts and circumstances in addition to the volume, price, time, and manner of the repurchases). For example, the safe harbor would not be available if the repurchases are made as part of a manipulative scheme to influence the closing price of a company’s securities, or are done to mask other motives, such as inflating or manipulating short-term earnings.

An issuer that does not disclose material information or otherwise engages in manipulative behavior will have broken the law. It is difficult to see that an insider who trades on material nonpublic information is usurping a corporate opportunity from the issuer, such that the issuer should claim any profits.

Of course, if an officer, director, or shareholder trades on the basis of material nonpublic information, that person probably has violated Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5. In U.S. v. Chiarella,[34] the U.S. Supreme Court articulated what the courts now call the “classic” theory of insider trading.[35] The Court stated that:

one who fails to disclose material information prior to the consummation of a transaction commits fraud only when he is under a duty to do so. And the duty to disclose arises when one party has information “that the other [party] is entitled to know because of a fiduciary or other similar relation of trust and confidence between them.”[36]

* * *

The federal courts have found violations of § 10 (b) where corporate insiders used undisclosed information for their own benefit. E. g., SEC v. Texas Gulf Sulphur Co., 401 F. 2d 833 (CA2 1968), cert. denied, 404 U. S. 1005 (1971). The cases also have emphasized, in accordance with the common-law rule, that “[t]he party charged with failing to disclose market information must be under a duty to disclose it.” Frigitemp Corp. v. Financial Dynamics Fund, Inc., 524 F. 2d 275, 282 (CA2 1975). Accordingly, a purchaser of stock who has no duty to a prospective seller because he is neither an insider nor a fiduciary has been held to have no obligation to reveal material facts. See General Time Corp. v. Talley Industries, Inc., 403 F. 2d 159, 164 (CA2 1968), cert. denied, 393 U. S. 1026 (1969).[37]

Unlike Section 16(b), Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 apply to any person, and not just to officers, directors, and ten-percent shareholders. Accordingly, Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 apply more broadly than does Section 16(b). Further, Section 16(b) penalizes officers, director, and ten-percent shareholders regardless of whether their trading was on the basis of material nonpublic information. Therefore, Section 16(b) is both over- and under-inclusive.

As noted, the 1941 SEC Report discusses the futility of trying to distinguish situations in which a covered person did or did not engage in insider trading:

The Commission is convinced that any legislation which sought to distinguish between situations where inside information is actually used and those where it is not used would be self-defeating because of the inherent difficulties of establishing the use of inside information in particular cases.[38]

I doubt that the SEC would make this argument today. Identifying persons who engage in insider trading is a central element of the Commission’s enforcement program.[39] In the wake of Dirks and Salmon,[40] it is essential that the Commission demonstrate that persons who trade (or their tippees) obtained, and traded on the basis of, material nonpublic information in breach of a fiduciary duty. Again, the SEC had not adopted Rule 10b-5 in 1934 or 1941, and the courts and SEC had not developed this area of the law. Moreover, at the time Congress was considering the Exchange Act, it also was considering legislation that fundamentally altered the federal rules of discovery.[41]

Six Months Is Not as Short as It Used to Be

In 1934, it may have been reasonable for Congress to assume that a covered person who traded within six months was trading with atypical speed; that is no longer the case. As we have discussed above, a six-month period is purely arbitrary because Section 16(b) liability does not depend on the investor’s actual knowledge. Even if that judgment were reasonable in 1934, it no longer reflects the world of today. By every measure, a six-month period no longer constitutes a short period of time for securities trading.

- In 1934, telecommunications consisted of telegrams, telex, radio, and telephone calls, recalling that long-distance calls required operator intervention and were expensive. Computers were barely in their infancy. No one had even conceived of the telecommunications revolution that we enjoy today.[42]

- There was no such thing as computer-driven algorithmic trading; the world’s first electronic computer did not begin functioning until 1945.[43] At that time, the idea of a personal computer would have seemed as absurd as a personal nuclear reactor. Today, quantitative hedge funds and proprietary trading firms may buy and sell financial instruments within a fraction of a second.

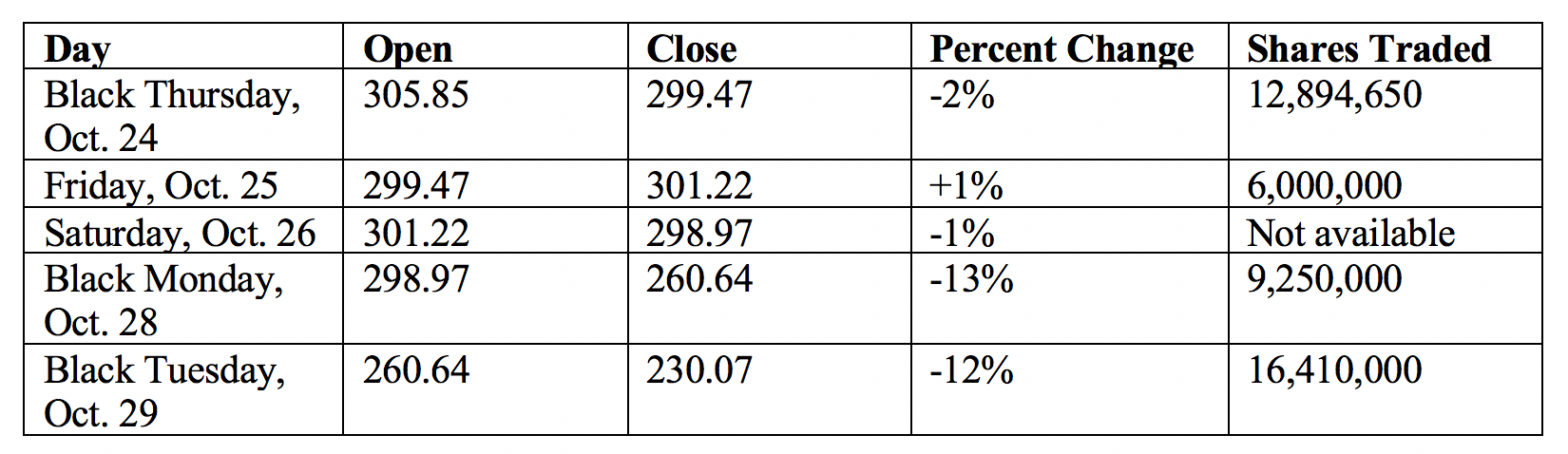

- Today’s securities trading volumes dwarf what Congress contemplated in 1934. For example, in the 1929 stock market crash, the volumes noted below were extraordinarily large for that era. Trading volume overwhelmed the “ticker” price dissemination mechanism, and it was hours late.

- By comparison, the 50-day average volume for Apple, i.e., one stock, is 26,769,660 shares.[44] In 2017, the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation noted that “on average, we process around 100 million transactions [e., not shares] each day, but we also need to be prepared to handle many multiples of that when markets are at their most volatile. Our record is 315 million transactions in a single day, which occurred in October 2008 at the height of the financial crisis.”[45]

In summary, the speed at which society communicates today vastly outstrips any assumptions that Congress made about short-swing transactions in 1934.

SEC Exemptive Rules

The SEC has adopted rules that mitigate some of the mischief of Section 16(b). Many of these exemptions protect the parties from liability in routine business transactions that may involve covered persons making purchases and sales within the prohibited six-month period. For example:

- Rule 16b-5 exempts gifts from Section 16(b). The exemption provides that “both the acquisition and the disposition of equity securities shall be exempt from the operation of section 16(b) of the Act if they are: (a) Bona fide gifts; or (b) transfers of securities by will or the laws of descent and distribution.”[46]

- Rule 16b-7 exempts many mergers, reclassifications, and consolidations. For example, Rule 16b-7(a)(1) exempts from Section 16(b) the acquisition of a security of a company, pursuant to a merger, reclassification, or consolidation, in exchange for a security of a company that before the merger, reclassification, or consolidation owned 85 percent or more of either: (i) the equity securities of all of the companies involved in the transaction; or (ii) the combined assets of the companies involved in the transactions.

These and other exemptive provisions prevent Section 16(b) from being an even greater obstacle to legitimate business than it currently creates. The exemptions also include a litany of SEC interpretations and court decisions, adding glosses to the provisions.[47]

Aggressive Plaintiffs’ Bar

Some members of the plaintiff’s bar have sought recovery under Section 16(b), proposing theories that are aggressive. As noted below, courts may reach very different conclusions on similar Section 16(b) claims.

1. “Deputization” of Directors

Some courts have held that “a corporation, partnership, trust, or other person” may be a director for purposes of Section 16 by expressly or impliedly “deputizing” another person to serve on its behalf on the board of directors of a Section 12 registrant.[48] A director is liable under Section 16(b) without regard to any amount of stock ownership.

Courts’ determinations run the gamut and are fact-specific. R&D summarize the key factors as follows:

- the entity recommended the director for election or appointment to the board;

- the entity recommended the director for the purpose of protecting or representing the entity’s interests rather than for the purpose of guiding or enhancing the issuer’s business activities;

- the director regularly gained access to material nonpublic information about the company;

- the director shared the confidential information with the entity; and

- the entity used the information to inform its investment decisions regarding the company’s securities.

Courts will deem a director by deputization only “if the director has a relation with the entity (e.g., as an employee or principal) that either allows the entity to influence the director’s decisions as a director or allows the director to influence the entity’s investment decisions regarding the company.” [49]

The SEC and some courts have concluded that a director by deputization may rely on the exemption in Rule 16b-3.

Investment entities must be mindful of the risk that a court will conclude that it has deputized a director. It is important to recall that a director who tips others in breach of duty risks violating Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5. As noted, Section 16(b) liability is not the only or even the best way to address insider trading.

2. Investment Manager Exemption

Rule 16a-1(a)(1) and subpart (v) create an exemption for investment managers. The SEC’s rule defines “beneficial owner” for purpose of Section 16 and not just for Section 16(a).[50] The rule excludes investment managers from the definition of “beneficial owner” under the following conditions:

- the owner of securities of such class held for the benefit of third parties or in customer or fiduciary accounts in the ordinary course of business;

- as long as such shares are acquired by such institutions or persons without the purpose or effect of changing or influencing control of the issuer or engaging in any arrangement subject to Rule 13d-3(b); and

- any person registered as an investment adviser under Section 203 of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 or under the laws of any state.

Given that many hedge fund managers invest their own funds along with outside investors,[51] some plaintiffs’ lawyers have argued that the manager is not investing purely for the benefit of third parties. As a result, some plaintiffs’ attorneys have argued that hedge fund managers flunk the second prong of the test and are not entitled to the investment adviser exemption. The courts have split on that argument. The structure of the fund may offer some protection from such claims, but practitioners indicate that the litigation risk is significant.[52]

Money managers were concerned that a covered person who received a fee for managing an investment account that holds the issuer’s securities would have an indirect pecuniary interest in those securities and therefore would be subject to Section 16(b). In response to those concerns, the SEC added subsection Rule 16a-1(a)(2)(ii)(C) to the rule, creating an exemption for performance-related fees. The courts have issued numerous opinions delineating when they will and will not apply the exemption.[53]

3. Definition of a “Group”

In a recent case, a plaintiff unsuccessfully argued that every discretionary account under the control of an investment adviser is member of a “group” and therefore subject to the short swing transaction provision of Section 16(b). In Rubenstein v. International Value Advisers LLC et al.[54], the investment adviser International Value Advisers LLC (IVA) and two of its principals managed funds and separately managed client accounts that purchased shares in DeVry Education Group (DeVry), a public company. IVA had developed a control purpose for purposes of Section 13(d) under the Exchange Act and accordingly filed a Schedule 13D.[55] A customer of IVA “John Doe” had a brokerage account that IVA managed and to which John Doe granted discretionary trading authority. IVA subsequently purchased shares in DeVry for that account and subsequently sold those shares in less than six months. The plaintiff argued that the Section 16(b) 10% shareholder liability provision applied to all such accounts. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit disagreed:

Between June and December 2016, the IVA defendants reported on ownership reports filed under Section 13(d) and Section 16(a) of the ’34 Act that they beneficially owned, through their voting and investment power over their advisee-clients, more than 10% of DeVry’s outstanding common stock. Specifically, at various times in 2016, the IVA defendants filed Schedule 13Ds with the SEC indicating that, in accumulating their position in DeVry, they had formed a “control purpose” with respect to DeVry and that they sought the appointment of IVA’s managing partner to the DeVry board to represent the investment interests of IVA and its clients who held DeVry shares. *** In July 2016, IVA, as investment manager for John Doe’s account, purchased 31,847 shares of DeVry and within six months sold DeVry shares at a profit.[56]

The court notes that without question, Section 16(b) liability applies to the other accounts in the group. The plaintiff alleged that the John Doe account was part of the group and therefore subject to the disgorgement remedy. (IVF did not buy and sell or sell and buy other shares of DeVry within six months’ time.) The court disagreed for a number of reasons.

- Section 16(b) liability does not apply to a customer’s general grant of discretion. When customers grant discretion to an investment adviser, they grant authority to the adviser to trade securities generally, not with respect to one issuer. Section 16(b) only addresses trading in one issuer, not several.

- Courts should not read Section 16(b) broadly. “The plaintiff argues that a narrow reading will enable investment managers to evade Section 16(b) and to abuse inside information by trading in client funds rather than their 12 own funds because client funds may not be subject to disgorgement.” First, citing Gollust and other decisions[57], the U.S. Supreme Court has cautioned against exceeding the narrowly drawn limits of the statute. Moreover, the court notes that:

Exempting certain client profits from Section 16(b) does not insulate investment advisors from liability under the more general anti-fraud provisions of the ‘34 Act: Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5. If IVA had improperly used inside information to trade in its clients’ accounts, it could be subject to Rule 10b-5, regardless of whether its clients were part of an insider group. Section 16(b) addresses only a narrow class of potential insider trading. By contrast, Rule 10b-5 addresses a broader sphere, including the insider trading that Rubenstein [the plaintiff] asks Section 16(b) to police. Trading that passes muster under Section 16(b) may not do so under Rule 10b-5. Rubenstein’s fear that our holding will offer a safe harbor to investment managers engaged in insider trading is consequently unwarranted. Suffice it to say that his complaint contains no allegations that Rule 10b-5 has been violated, and that provision plays no part in our resolution of this case.[58]

- There is no legal basis for ascribing the actions of one of the adviser’s clients to another, purely because they share the same manager that exercises investment discretion.

An investment advisory client does not form a group with its investment adviser by merely entering into an investment advisory relationship. Nor does an investor become a member of a group solely because his or her advisor caused other (or all) of its clients to invest in securities of the same issuer. And Rubenstein points us to nothing else that might constitute an “agreement” or demonstrate a “common objective” to trade in the securities of “an issuer.”[59]

The court further noted:

Rubenstein would have us treat all investors as though they were conscious of the securities held by their advisors’ other clients and would mandate that they tailor their investment decisions to those other clients’ trades. *** Section 16(b) is not designed to threaten liability based on the trades of other investors to whom a defendant’s only connection is sharing an investment advisor. ***Rubenstein would hold a retiree on the beach in Florida liable when he fails to conduct an ongoing analysis of his IRA manager’s trading in other clients’ accounts. We decline to go down this road.[60]

The court probably is speaking “tongue in cheek.” It probably would be impossible or illegal for one client to obtain information about another client’s trading activity. Nonetheless, the opinion illustrates the absurd outcome that would result from the plaintiff’s argument.

The Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit issued a similar ruling in another case involving the same plaintiff.[61] Although these decisions clear up some ambiguities in the law of Section 16(b), “it remains to be seen whether courts will apply a similar analysis where the adviser’s clients are investment funds under common control with the adviser.”[62]

Although the Second Circuit ultimately vindicated the defendants in both cases, it must have cost them hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees and other expenses to fend off aggressive plaintiffs with “creative” new theories of liability at the intersection of Section 13(d) and Section 16(b). Such wasteful litigation does nothing to strengthen the integrity of our capital markets and to protect investors from shameful behavior. Indeed, it has the opposite effect. Moreover, many defendants will not have the disposition nor the resources to litigate a case in the district court and the appellate court. Some defendants, given the choice between a pyrrhic victory and a less costly settlement, will pay the plaintiff go away.

Given the uncertainty of the outcome and the expense of litigating such cases, some investment managers settle with these lawyers, regardless of the merits of the cases. Such outcomes do not further whatever public policy benefits Congress sought to achieve with Section 16(b); instead, plaintiffs or their lawyers force investment advisers to engage in nothing more than a cost/benefit analysis of whether to settle or litigate.

Distraction for Management

In the 1941 SEC Report, the SEC claimed that Section 16(b) protected shareholders by ensuring that officers and directors would focus their attention on managing the issuer’s business and not trading for their own account. “It is to be doubted whether the interests of security holders are benefited when the attention of their officers and directors is diverted from the corporation’s affairs to stock market speculation in its securities.” The argument is specious.

Why is this the government’s concern? Investors and stock prices are the best judge of whether management is doing its job, not a prohibition on trading. Presumably, investors only care about results, not how officers and directors are spending their time. Indeed, one could argue that it is less of a distraction for covered persons to trade the stock of the issuer than it is for them to trade the stock of another company, for which they would have to devote more time to learn about that issuer and its prospects. Even if one accepted this dubious rationale, it should not apply to 10-percent shareholders who are not also officers or directors of the company.

The federal securities laws should not propose to tell management how to spend its time. Stock prices and investors are the best judges of whether management is doing its job.

Conclusions and Recommendation

This paper outlines only a small sample of the interpretive questions that Section 16(b) has caused. R&D’s materials are replete with discussions of interpretive questions that this provision has created. If Section 16(b) served a useful public purpose, the interpretive issues described above would be an unavoidable cost of applying a simple concept to a complex world. As shown, however, Section 16(b) is an ineffective deterrent against true insider trading. Section 16(b) does not confer a public benefit proportionate to its attendant cost. Notwithstanding the Supreme Court’s pronouncements, if a proposed transaction does not fall squarely within an exemption, legal expense, delay, and uncertainty may delay or prevent what would otherwise be a harmless transaction.

Other portions of the federal securities laws make actual insider trading illegal; prosecutors, the SEC, and private parties provide meaningful sanctions for violating those prohibitions. Further, other prohibitions, such as Section 9 and other aspects of Section 10 of the Exchange Act, along with rules such as Regulation SHO, prohibit the activities about which Congress was concerned. Section 16(b) has failed in its stated purpose, rewards an aggressive plaintiffs’ bar, creates needless complexity, and imposes punishing liability that is out of proportion or unrelated to the behavior it seeks to deter.

In my view, Congress simply should repeal Section 16(b). Congress could never take such action unless both political parties supported the change. It would be easy for one’s political opponents falsely to charge a member of Congress who supported the legislation with favoring insider trading. I appreciate that the political world does not always behave rationally; nonetheless, there is no public policy for retaining the provision, and there are good reasons for Congress to repeal it.

If Congress could not muster the support for outright repeal, there might be a more moderate compromise. Congress could repeal the private right of action and allow the SEC to impose sanctions for short-swing transactions. Congress would need to make clear that the SEC had authority to reshape the rule, given that courts have not always spoken with one voice on many of its provisions. Unlike some courts and plaintiffs’ attorneys, the author hopes that the SEC would use better judgment as to when a covered person had violated Section 16(b). Moreover, Congress should make clear that violators should pay any disgorgement to the U.S. Treasury, rather than to enrich creative plaintiffs or aggressive plaintiffs’ attorneys.

Attachment 1

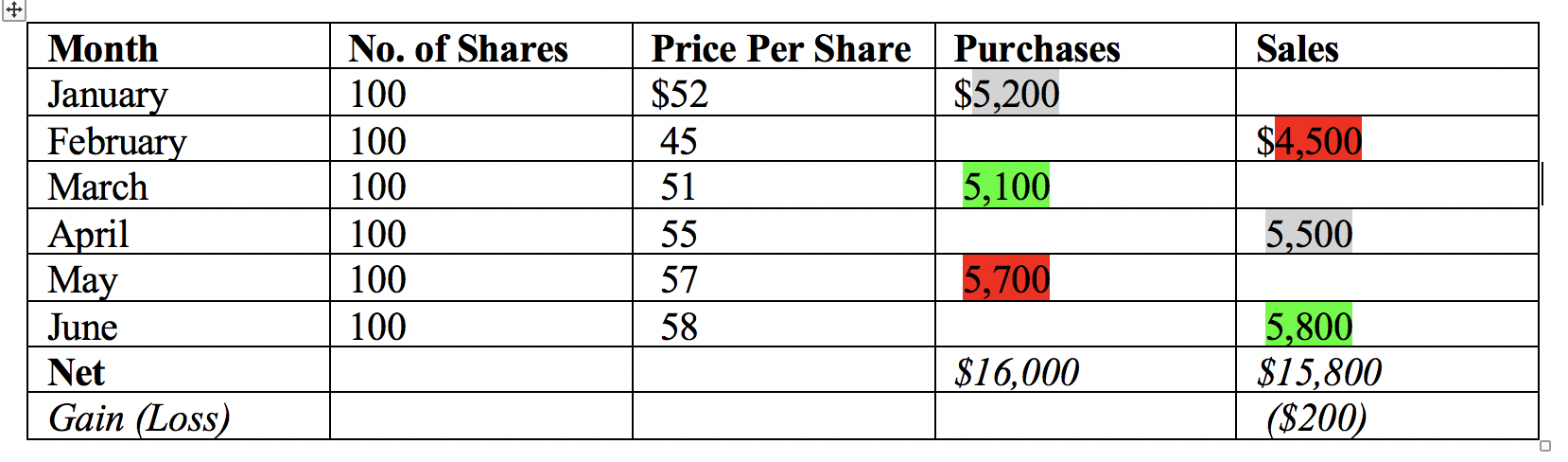

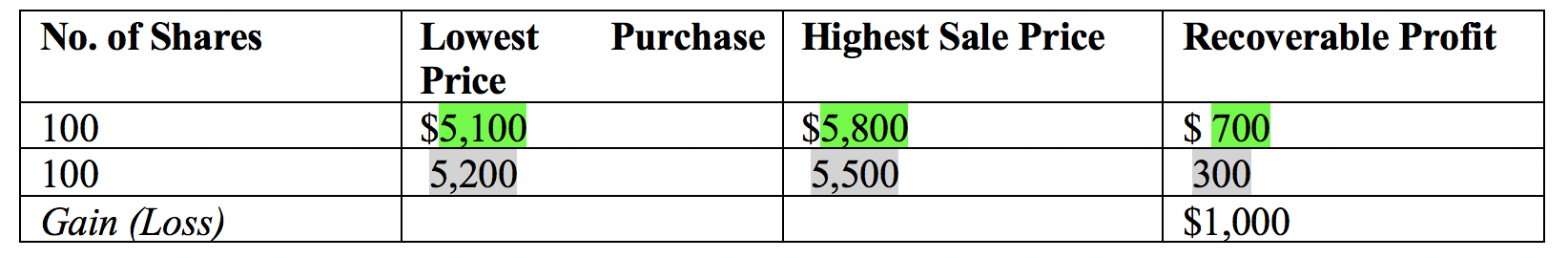

According to R&D, the Section 16(b) calculations would be as follows:

R&D further note: “The remaining transactions are disregarded because the only remaining purchase was $58 a share, resulting in a loss when matched with the remaining sales. Those losses may not be used to reduce the amount of recoverable profits.”

[1] © Stuart J. Kaswell 2019, 2020, who has granted permission to the ABA to publish this article in accordance with the ABA’s release, a copy of which is incorporated by reference. Stuart Kaswell is an experienced financial services lawyer. He has worked at the Securities and Exchange Commission, as securities counsel to the Committee on Energy and Commerce of the U.S. House of Representatives (when it had securities jurisdiction), and has been a partner at two law firms and general counsel of two financial trade associations. Mr. Kaswell wishes to thank Alan L. Dye, Esq. for reviewing the draft and other technical assistance, including access to Romeo & Dye, Section 16 Deskbook (Summer 2019) (hereinafter R&D) and to other materials from section16.net. Mr. Kaswell also wishes to thank Stephen A. Blumethal, Esq. for reading a draft of the article and for his suggestions. All of the opinions and recommendations in this article are the author’s alone and do not reflect the views of any reviewer or of any current or prior clients or employers. Any errors are the author’s alone.

[2] The author does not suggest that Congress repeal Section 16(a) of the Exchange Act. That provision requires certain insiders publicly to disclose their securities transactions.

[3] In its current form, Section 16(b) provides:

For the purpose of preventing the unfair use of information which may have been obtained by such beneficial owner, director, or officer by reason of his relationship to the issuer, any profit realized by him from any purchase and sale, or any sale and purchase, of any equity security of such issuer (other than an exempted security) or a security-based swap agreement involving any such equity security within any period of less than six months, unless such security or security-based swap agreement was acquired in good faith in connection with a debt previously contracted, shall inure to and be recoverable by the issuer, irrespective of any intention on the part of such beneficial owner, director, or officer in entering into such transaction of holding the security or security-based swap agreement purchased or of not repurchasing the security or security-based swap agreement sold for a period exceeding six months. Suit to recover such profit may be instituted at law or in equity in any court of competent jurisdiction by the issuer, or by the owner of any security of the issuer in the name and in behalf [sic] of the issuer if the issuer shall fail or refuse to bring such suit within sixty days after request or shall fail diligently to prosecute the same thereafter; but no such suit shall be brought more than two years after the date such profit was realized. This subsection shall not be construed to cover any transaction where such beneficial owner was not such both at the time of the purchase and sale, or the sale and purchase, of the security or security-based swap agreement involved, or any transaction or transactions which the Commission by rules and regulations may exempt as not comprehended within the purpose of this subsection. [Emphasis added.]

Section 16 includes other provisions, such as:

- subsection (a) requiring covered persons to disclose changes in ownership of such equity securities; and

- subsection (c) prohibiting covered persons from selling short any equity of the issuer.

Congress amended 16(b) as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2001, 106th Cong., Pub. L. No. 554, (Appropriations Act) and the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 (Dodd-Frank Act). Congress amended the subsection to add security-based swaps into its various provisions.

The Appropriations Act added, and the Dodd-Frank Act amended, Section 3A of the Exchange Act. Subsection 3A(b)(3) currently provides:

(3) Except as provided in section 16(a) with respect to reporting requirements, the Commission is prohibited from—

(A) promulgating, interpreting, or enforcing rules; or

(B) issuing orders of general applicability;

under this title in a manner that imposes or specifies reporting or recordkeeping requirements, procedures, or standards as prophylactic measures against fraud, manipulation, or insider trading with respect to any security-based swap agreement.

[4] See double underlined text in note 3, supra.

[5] Hearings on H.R. 7852 and H.R. 8720 before the House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, 73d Cong., 2d Sess., 136 (1934) (testimony of Thomas G. Corcoran) , as quoted in Gollust et al v. Mendell et al, 501 U.S. 115, 126 (1991). See also Reliance Electric Co. v. Emerson Electric Co., 404 U.S. 418 (1972) in which the U.S. Supreme Court states:

As one court observed:

In order to achieve its goals, Congress chose a relatively arbitrary rule capable of easy administration. The objective standard of Section 16(b) imposes strict liability upon substantially all transactions occurring within the statutory time period, regardless of the intent of the insider or the existence of actual speculation. This approach maximized the ability of the rule to eradicate speculative abuses by reducing difficulties in proof. Such arbitrary and sweeping coverage was deemed necessary to insure the optimum prophylactic effect. Bershad v. McDonough,428 F.2d 693, 696.

Thus [the U.S. Supreme Court explained] Congress did not reach every transaction in which an investor actually relies on inside information. A person avoids liability if he does not meet the statutory definition of an ‘insider,’ or if he sells more than six months after purchase. Liability cannot be imposed simply because the investor structured his transaction with the intent of avoiding liability under § 16(b). The question is, rather, whether the method used to ‘avoid’ liability is one permitted by the statute.

In Donoghue v. Bulldog Investors General Partnership, 696 F.3d 170 (2012), the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit rejected a claim that Section 16(b) is unconstitutional “because it presents no live case or controversy affording standing to sue.” The defendant, Bulldog, argued that the plaintiff, Donoghue, lacked standing because she had not suffered any actual injury. The Second Circuit rejected that argument, noting, among other things, that:

Nor can Bulldog deny any injury to the issuer from its short-swing trading by pointing to the fact that § 16(b) operates without regard to whether the statutory fiduciaries were actually privy to inside information or whether they traded with the intent to profit from such information. This confuses the wrongdoing that prompted the enactment of § 16(b)—trading on inside information—with the legal right that Congress created to address that wrongdoing—a 10% beneficial owner’s fiduciary duty to the issuer not to engage in any short-swing trading.

The U.S. Supreme Court denied Bulldog’s petition for certiorari, 569 U.S. 994 (2012).

[6] R&D, supra note 1, at 390.

[7] Stock Exchange Practices, Report of the Committee on Banking and Currency, United States Senate, Pursuant to S. Res. 84 (72d Cong.), 73d Cong., 2d Sess., Report No. 1455 (the Pecora Report). See also Hearings before the Committee on Banking and Currency, U.S. Senate, 73rd Cong., 1st Sess. on S. Res. 84 (72d Cong.), at 6555 (discussing early versions of what became Section 16(b)). Thomas Corcoran, one of the drafters of the federal securities laws, discussed the proposed short-swing transaction with Senator Hamilton F. Kean (R-NJ). Earlier in the hearing, Senator Kean and Mr. Corcoran discussed short selling and customers’ failures to deliver certificates by the date of settlement. They engaged in the following shameful discussion:

Senator Kean: There are a great many women that order you to sell some bonds, and then they do not come down for 2 or 3 days, but you are forced to deliver them.

Mr. Corcoran: Sir, I cannot pretend in this statute to govern the vagaries of women customers.

Id. at 6506.

[8] Pecora Report, supra note 7, at 55.

[9] Pecora Report, supra note 7, at 68.

[10] SEC Historical Society, Fair to All People: The SEC and the Regulation of Insider Trading (reprinted by permission).

[11] See discussion below.

[12] See discussion below.

[13] Report of the Securities and Exchange Commission on Proposals for Amendments to the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, Aug. 7, 1941, Printed for the Use of the Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, 77th Cong., 1st Sess., at 37–38 (1941 SEC Report).

[14] Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act currently provides that:

It shall be unlawful for any person, directly or indirectly, by the use of any means or instrumentality of interstate commerce or of the mails, or of any facility of any national securities exchange or any security not so registered, or any securities based swap agreement any manipulative or deceptive device or contrivance in contravention of such rules and regulations as the Commission may prescribe as necessary or appropriate in the public interest or for the protection of investors.

Rule 10b-5 provides that:

It shall be unlawful for any person, directly or indirectly, by the use of any means or instrumentality of interstate commerce, or of the mails or of any facility of any national securities exchange,

(a) To employ any device, scheme, or artifice to defraud,

(b) To make any untrue statement of a material fact or to omit to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statements made, in the light of the circumstances under which they were made, not misleading, or

(c) To engage in any act, practice, or course of business which operates or would operate as a fraud or deceit upon any person,

in connection with the purchase or sale of any security.

[15] Exchange Act Release 3230 (May 31, 1942). Rule 10b-5 is quite similar to Section 17(a) of the Securities Act. However, the SEC crafted Rule 10b-5 to be slightly broader than Section 17(a). See In the Matter of Cady, Roberts & Co., File No. 8-3925, Nov. 8, 1961, at 911 and n.11.

[16] In the Matter of Cady, Roberts & Co., File No. 8-3925, Nov. 8, 1961. From today’s perspective, the SEC was extremely lenient in this case. It suspended the representative for 20 days. Apparently, the SEC did not sanction the issuer’s board member who tipped the representative, even though the board member also was a principal at the broker-dealer. The settlement did not include a sanction against the broker-dealer.

[17] Section 21A of the Exchange Act. See also Hearing before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigation of the Committee on Energy and Commerce, U.S. House of Representatives, Dec. 11, 1986, Serial No 99-179, Testimony of the Hon. John Shad, Chairman SEC, at 53: “Prior [to Congress’s enactment of] the Insider Trading Sanctions Act of 1984 (ITSA), insider traders were required only to disgorge their illegal profits, which was not much of a deterrent. Now they are subject to fines of up to three times their profits.” The author was Associate Minority (Republican) Counsel to the Committee and was present at the hearing. Id. at 191.

[18] See Kaswell, An Insider’s View of the Insider Trading and Securities Fraud Enforcement Act of 1988, 45 Bus. Law 245 (1989), revised and republished in American Bar Association, Securities Law Administration, Litigation, and Enforcement, Selected Articles on Federal Securities Law, Vol. III 252 (1991) (Kaswell, ITSFEA). This article also discusses the Securities Enforcement Remedies and Penny Stock Reform Act of 1990 at n.53

[19] Salmon v. United States, 580 U.S. ___ ;137 S. Ct. 420 (2016); 196 L.Ed.2d 351 (citing Dirks v. SEC, 463 U.S. 646 (1983)).

[20] 17 C.F.R. § 240.14e-3, Release 33-6239; 34-17120; 45 Fed. Reg. 60410 (Sept. 12, 1980).

[21] E.g., Matthews, Prosecutors Broadly Use Mail-Fraud, Wire Fraud Statues, Wall St. J., June 9, 2015.

[22] Of course, the courts have found private rights of action implicit in Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 as well as in other provisions. E.g., Superintendent of Ins. of N.Y. v. Bankers Life & Casualty Co., 404 U.S. 6 (1971); Central Bank of Denver, N.A, v. First Interstate Bank of Denver, 511 U.S. 164 (1994). See also Hon. Elisse B. Walter, Commissioner, SEC, Remarks Before the FINRA Institute at Wharton Certified Regulatory and Compliance Professional Program, Nov. 8, 2011.

[23] R&D, supra note 1. See also discussion of Rubenstein v. International Value Advisers, LLC, infra.

[24] R&D, supra note 1, at 364.

[25] R&D, supra note 1, at 367–68.

[26] R&D at 642-643. Courts may not impose liability if the parties rescinded for purposes unrelated to Section 16(b). Id. The U.S District Court for the Southern District of New York recently held that a party that rescinds the purchase of securities before settlement is not liable under Section 16(b). The court stated that the defendant “did not rescind a purchase of shares; rather, a purchase never occurred because he cancelled the transaction and was not irrevocably committed to it. Connell v. Johnson, No 20 Civ 1864 (LLS), May 27, 2020. “This the first time a court has addressed whether a market transaction that is canceled through the broker’s error account is subject to Section 16.” Romeo and Dye, Section 16 Updates, Vol. 30. No. 2, June 2020 (R&D June 2020), at 6.

[27] R&D, supra note 1, at 365.

[28] In very limited circumstances, courts have sought to exclude certain transactions from the scope of Section 16(b). R&D, supra note 1, at 369, but this “pragmatic exception to the objective test” is too limited to a cure Section 16(b) of its inherent arbitrariness. Moreover, the courts have limited the exceptions such that it would be risky for covered persons to rely on them and them hope to vindicate their trading activity in an expensive legal battle.

[29] R&D, supra note 1, at 367.

[30] R&D, supra note 1, at 488 (citing Smolowe v. Delendo Corp. 136 F.2d at 239).

[31] 46 Fed. Reg. 48097, 48162 (Oct. 1, 1981), as cited in R&D, supra note 1, at 488.

[32] See Attachment 1, infra, for an example of the onerous methodology that the courts adopted for calculating gains.

[33] R&D, supra note 1, at 364.

[34] 455 U.S. 222 (1980).

[35] In U.S. v. O’Hagan, 521 U.S. 642, 643 (1997), the U.S. Supreme Court noted:

Under the “traditional” or “classical theory” of insider trading liability, a violation of § l0(b) and Rule l0b-5 occurs when a corporate insider trades in his corporation’s securities on the basis of material, confidential information he has obtained by reason of his position. Such trading qualifies as a “deceptive device” because there is a relationship of trust and confidence between the corporation’s shareholders and the insider that gives rise to a duty to disclose or abstain from trading. Chiarella v. United States, 445 U. S. 222, 228–29.

[36] Id. at 228 (citing “Restatement (Second) of Torts § 551(2)(a) (1976). See James & Gray, Misrepresentation—Part II, 37 Md. L. Rev. 488, 523-527 (1978). As regards securities transactions, the American Law Institute recognizes that ‘silence when there is a duty to . . . speak may be a fraudulent act.’ ALI, Federal Securities Code § 262 (b) (Prop. Off. Draft 1978).”).

[37] Id. at 229 (citations omitted).

[38] 1941 SEC Report, at 37.

[39] In 2019, the SEC brought cases against “42 individuals who allegedly misappropriated or traded unlawfully on material, nonpublic information. . . .” SEC Division of Enforcement, 2019 Annual Report, at 24. Six percent of the Commission’s “standalone” cases involved insider trading. Id. at 15.

[40] Dirks v. SEC, 463 U.S. 646 (1983); Salman v. U.S., 137 S. Ct. 420 (2016). Rule 14e-3 does not require the SEC to prove that the person trading (or his or her tippee) traded in breach of a duty.

[41] It also may be that the lack of discovery in federal courts contributed to Congress’s decision to enact Section 16(b). During the first third of the 20th century, Congress, the federal judiciary, and lawyers debated whether Congress should expand the limited discovery rules for civil litigation in federal courts. Traditionally, English and American courts opposed extensive discovery as intrusive and an invasion of citizens’ privacy. Existing federal law discouraged discovery and uniformity. “The Conformity Act of 1872 . . . required (excepting equity and admiralty cases) that the civil procedure in each federal trial court [must] conform ‘as near as may be’ with that of the state in which the court sat.” In 1934 and as part of the New Deal, Congress enacted the Rules Enabling Act of 1934 (Enabling Act), i.e., the same year that Congress enacted the Exchange Act. The Enabling Act authorized the federal courts to adopt the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which they did in 1938 (Federal Rules). The Federal Rules substantially increased discovery in federal civil litigation and created more uniformity across the country. Subrin, Fishing Expeditions Allowed: The Historical Background of the 1938 Federal Discovery Rules, 39 Boston College L. Rev. 691 (1998). Although it is not clear from the legislative history that the lack of discovery in federal court was a factor in Congress’s decision to enact Section 16(b), presumably Congress was aware of the debate over the Enabling Act. Perhaps the framers of the Exchange Act did not wish to assume that Congress would be successful in expanding discovery in federal court to facilitate the SEC or a private party’s ability to prove a claim of willful insider trading. If Congress was concerned about the lack of discovery in federal courts, the Enabling Act and the Federal Rules are further justification to repeal Section 16(b) and its imposition of strict liability.

[42] In 1945, Dr. Vannevar Bush of MIT wrote “As We May Think”, a groundbreaking article that imagines a world of rapid communication and data storage. It is a remarkable, if not perfect, prediction of how people would calculate and share data in the future. Expressing frustration at the slow pace of data dissemination and the difficulty of finding relevant information, Dr. Bush noted the example of “[Gregor] Mendel’s concept of the laws of genetics [that] was lost to the world for a generation because his publication did not reach the few who were capable of grasping and extending it; and this sort of catastrophe is undoubtedly being repeated all about us, as truly significant attainments become lost in the mass of the inconsequential.” Dr. Vannevar Bush, As We May Think, Atlantic Monthly, July 1945.

[43] ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer). The U.S. Army built ENIAC between 1943 and 1945; it had nearly 18,000 vacuum tubes. See Birth of a Computer, Computer History Museum.

[44] Accessed on Nov. 8, 2019.

[45] Joseph Cuniglio, Director, NSCC Operations, How does a market stress event or high-volume trading day impact DTCC systems?, DTCC Connection, Nov. 6, 2017.

[46] 34- 288869, 56 Fed. Reg. 7270, at 7272 (Feb. 21, 1991).

[47] R&D, supra note 1, at 523 et seq.

[48] R&D, supra note 1, at 90.

[49] R&D, supra note 1, at 168–72. See also Rule 16-3, which exempts certain transactions by an officer or director with the issuer. Id. at 692–94.

[50] The introductory language of Rule 16a-1 provides: “Definition of terms. Terms defined in this rule shall apply solely to section 16 of the Act and the rules thereunder. These terms shall not be limited to section 16(a) of the Act but also shall apply to all other subsections under section 16 of the Act.” By excluding an entity from the definition of “beneficial owner,” the rule excludes entities from liability under Section 16(b).

[51] Prospective investors in a hedge fund often seek to know whether employees of the fund manager have invested their own money in that hedge fund. In response to a request from the Managed Funds Association, the SEC staff clarified and liberalized restrictions permitting more employees to invest in the fund than under the SEC’s prior views. SEC, Division of Investment Management, Investment Company Act of 1940—Section 7 and Rule 3c-5

Managed Funds Association, Feb. 6, 2014, incoming letter from Stuart J. Kaswell, General Counsel, Managed Funds Association, Feb. 5, 2014.

[52] Michael Swartz, Schulte Roth & Zabel, Hedge Fund Legal & Compliance Digest, Apr. 6, 2017.

[53] Rule 16a-1(a)(2)(ii)(C) provides:

(2) Other than for purposes of determining whether a person is a beneficial owner of more than ten percent of any class of equity securities registered under Section 12 of the Act, the term beneficial owner shall mean any person who, directly or indirectly, through any contract, arrangement, understanding, relationship or otherwise, has or shares a direct or indirect pecuniary interest in the equity securities, subject to the following:

***

(ii) The term indirect pecuniary interest in any class of equity securities shall include, but not be limited to:

***

(C) A performance-related fee, other than an asset-based fee, received by any broker, dealer, bank, insurance company, investment company, investment adviser, investment manager, trustee or person or entity performing a similar function; provided, however, that no pecuniary interest shall be present where:

(1) The performance-related fee, regardless of when payable, is calculated based upon net capital gains and/or net capital appreciation generated from the portfolio or from the fiduciary’s overall performance over a period of one year or more; and

(2) Equity securities of the issuer do not account for more than ten percent of the market value of the portfolio. A right to a nonperformance-related fee alone shall not represent a pecuniary interest in the securities.

R&D at 292 et seq.

[54] 959 F. 3d 541 (2d Cir. 2020) available at GovInfo.gov. See also R&D June 2020,

[55] In 1968, Congress amended the Exchange Act to add section 13(d) as part of the Williams Act. Briefly, that provision requires purchasers of more than 5% of a public company to file disclosure statements with the SEC. “The primary purpose of the Williams Act was to regulate cash tender offers and other potential acquisitions of corporate control by requiring acquirers of registered securities to make public disclosure of their actions and intentions.” R&D at 102. The SEC adopted rules for calculating the 10% ownership under Section 16(b) by employing the standards in Section 13(d) and the rules thereunder. Id at 100.

[56] Rubenstein supra, at 6.

[57] Supra at note 5.

[58] Rubenstein at 14-15.

[59] Id at 12. See also R&D June 2020, at 5.

[60] Id. at 21.

[61] Rubenstein v. ROFAM INV., LLC et al., 19-796-cv, Summary Order,2d Cir, May 20, 2020, affirming Rubenstein v. Berkowitz et al and Sears Holdings Corp., 17-CV-821 (JPO), SDNY, March 27, 2019.

[62] R&D, June 2020, at 5.