What Is a Securitization?

Securitization is a subset of structured finance. Structured finance transactions are generally finance transactions that involve the isolation of a pool of financial assets from the originator of those assets and a loan that relies on the strength of the assets rather than the creditworthiness of the owner. A securitization is a transaction in which a sponsor or originator obtains funding by causing a special purpose entity to issue securities backed by (and paid from) the proceeds of financial assets. The underlying assets are generally originated by companies seeking funds to finance operations or other corporate initiatives.

A variety of assets are used in securitizations. For example, securitizations may involve residential or commercial mortgages, credit card receivables, auto loans, student loans, corporate loans, or other financial assets.

A key feature of securitizations is legal isolation of the underlying assets. The underlying assets are transferred to the issuer of the securities on a “true sale” basis, and the issuer is structured in such a way as to be isolated from the bankruptcy risk of the originator.

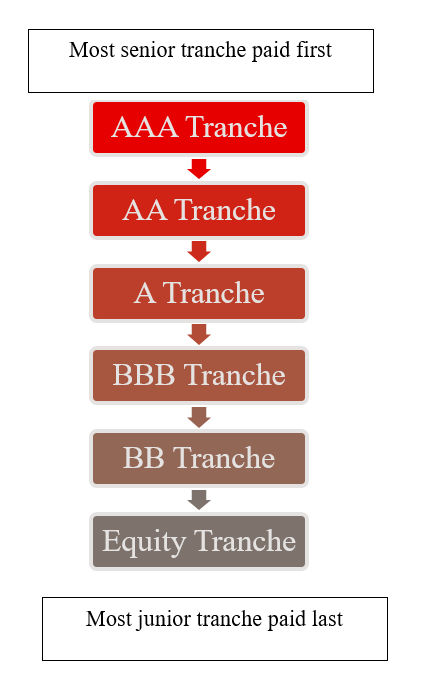

Another feature of securitizations is credit enhancement. There are several methods for credit enhancement, including “tranching,” whereby the bonds are divided in a number of tranches[1] with varying risk profiles (see Figure 1 for an example of tranches). Another is “overcollateralization,” which involves having more assets than necessary to cover payment on the securities.

Figure 1: Example of tranching. A flow chart illustrates that the most senior tranche is paid first and the most junior tranche last.

Why Securitize?

The credit enhancement inherent to securitizations, especially due to the aforementioned legal isolation techniques, permits the originating companies to obtain higher ratings than if such companies were to obtain a traditional loan. Consequently, the originating companies can obtain financing at a lower cost of funding.

Main Parties and Legal Documents

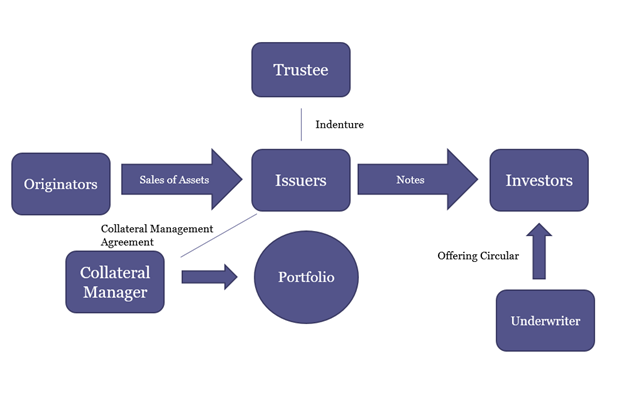

While securitizations come in a variety of structures, the following highlights the main parties and documents in a typical securitization.

Parties

The Originator/Sponsor

The originator generates (originates) and/or owns the receivables (the cash-flowing assets) that it seeks to securitize. A securitization may have many originators. The sponsor is the person who initiates and drives the securitization. In some transactions, the originator is also the sponsor of the transaction.

The Servicer

The servicer is the person who performs the administrative services related to the collection of the receivables. The servicer may also have active management responsibilities with respect to the receivables/underlying assets, if the securitization’s portfolio is “dynamic.”

The Trustee/Collateral Agent

The Trustee/Collateral Agent is the person/organization (typically a bank) that holds the security interest on behalf of the investors and may perform certain other duties under the transaction documents. The person serving as Trustee may have multiple additional roles in a transaction, such as serving as custodian, account bank, or collateral administrator.

The Issuer

The Issuer is an entity created solely for purposes of a securitization and is responsible, among other duties, for issuing the securities. Some transactions have more than one issuer.

The Underwriter

The underwriter is the person responsible for arranging for the sale of the Issuer’s securities to the initial investors.

The Investors

The investors are the persons who invest in the securitization transaction by purchasing the securities originally issued by the Issuer and placed by the underwriter.

(See Figure 2 for a relationship diagram with typical transaction parties.)

Figure 2: Securitization Parties. A flow chart indicates the relationships between the main parties in a typical securitization.

Main Legal Documents

The two main legal documents in a securitization transaction are generally the indenture and the offering document.

Indenture

The indenture provides the terms of the securities issued in the securitization and describes the rights and duties of transaction parties.

Offering Document

The offering document is the main disclosure document that investors use to make their investment decisions. The offering document includes a description of the risk factors, the structure of the transaction, and the terms of the securities.

Bankruptcy Law

One of the main objectives in a securitization is to isolate the portfolio of underlying assets from the bankruptcy risk of the originator of those assets. Features of a securitization that are designed to achieve this objective include structuring the Issuer as a special purpose entity and transferring the underlying assets from the originator to the Issuer in a true sale.

Securities Law

In securitization transactions not registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”), the structure of the transaction and the types of investors investing in the transaction have to be carefully considered in order to meet the requirements of a private transaction. In registered transactions, the SEC reviews the offering document, and the document has to meet the disclosure requirements of a public transaction.

Other Regulatory Regimes

A number of other regulatory regimes can be relevant to securitizations. Examples include the restrictions on ownership or sponsorship of a “covered fund” by a banking entity under the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (the “Dodd-Frank Act”), the risk retention rules under the Dodd Frank Act, and, in transactions that securitize consumer loans, rules issued by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

[1] From the French word tranche, or “slice” in English.