The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (collectively, the “Regulators”) issued a joint “Statement on LIBOR Transition” (the “2020 Statement”)[1] on November 30, 2020. The stated purpose of the 2020 Statement was to “encourage banks to transition away from [USD] LIBOR as soon as possible.”[2] Included in the 2020 Statement was guidance that the Regulators believe that “entering into new contracts that use USD LIBOR as a reference rate after December 31, 2021, would create safety and soundness risks and will examine bank practices accordingly.”[3] As a result, the Regulators have urged banks to “cease entering into new contracts that use USD LIBOR as a reference rate as soon as practicable and in any event by December 31, 2021.”[4]

On October 20, 2021, a new “Joint Statement on Managing the LIBOR Transition” was issued by the Regulators together with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the National Credit Union Administration, and the State Bank and Credit Union Regulators (the “2021 Statement,” and together with the 2020 Statement, the “Regulators’ Joint Statements”)[5]. The 2021 Statement offered additional guidance on the interpretation of the term “new contracts” and specified that the term would include “an agreement that (i) creates additional LIBOR exposure for a supervised institution; or (ii) extends the term of an existing LIBOR contract.”[6] Additionally, the statement clarified that new draws under already existing committed credit facilities would not be viewed as new contracts for the purpose of the guidance under the Regulators’ Joint Statements.[7]

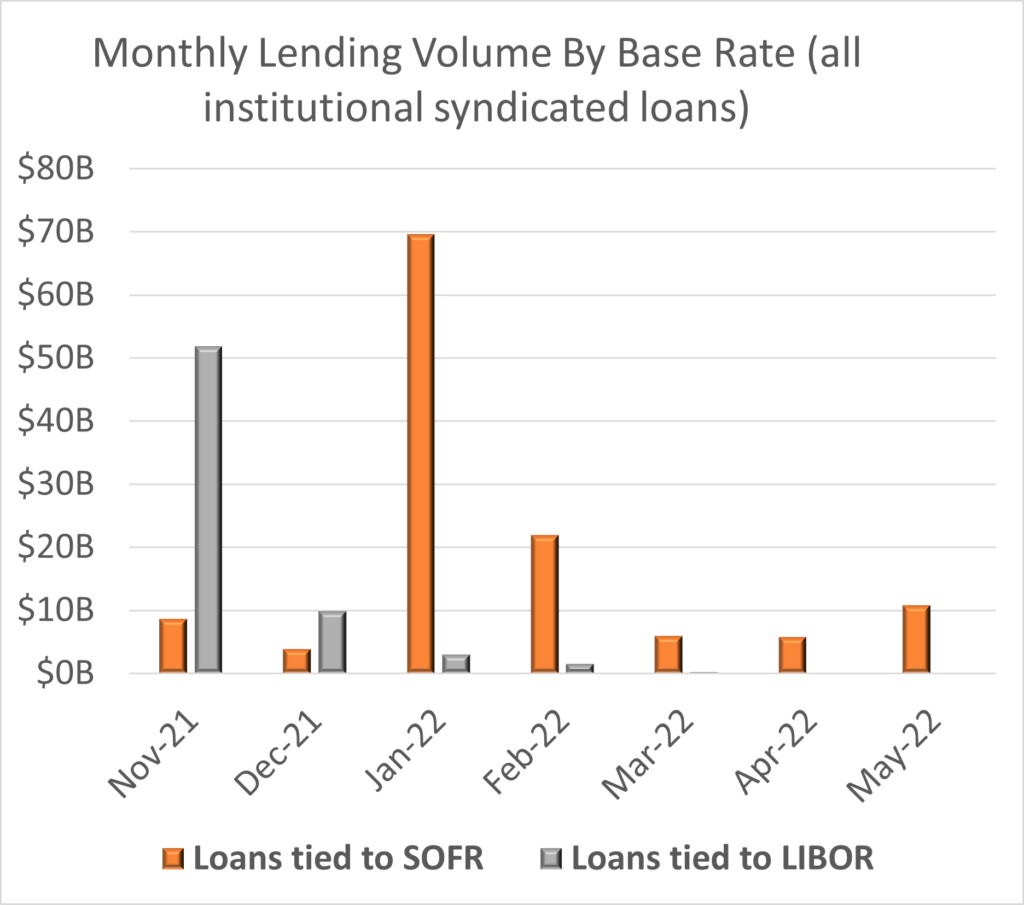

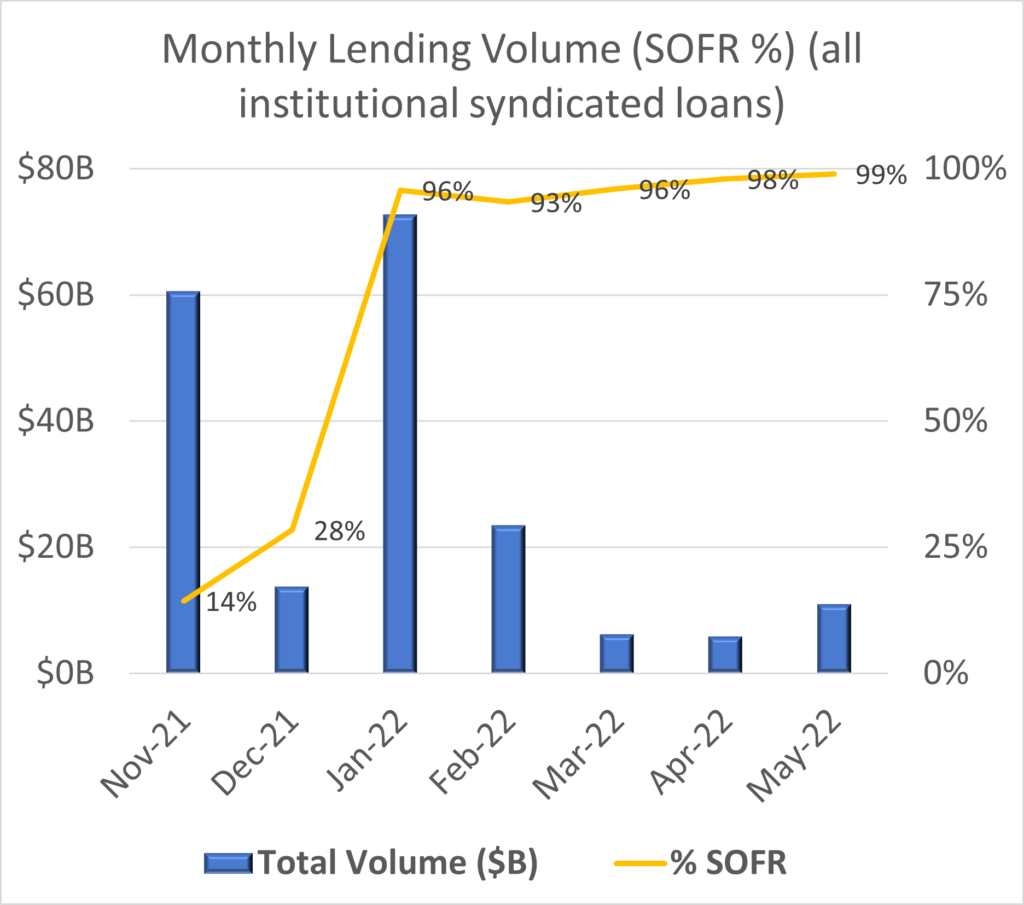

As a result of the Regulators’ Joint Statements, the vast majority of syndicated loan agreements that have closed on or after January 1, 2022, have used interest rate benchmarks other than LIBOR, primarily SOFR. From statistics provided by LevFinInsights (graphs representing these statistics are reproduced below), the pivot from LIBOR to SOFR in the institutional syndicated loans market has been drastic. While over 70% of institutional syndicated loans that launched in December 2021 still referenced LIBOR, less than 5% of institutional syndicated loans that launched in January 2022 reference LIBOR. The move to SOFR has continued in a similar split in the months that have followed since the beginning of 2022, with approximately 99% of institutional syndicated loans that launched in May 2022 referencing SOFR.

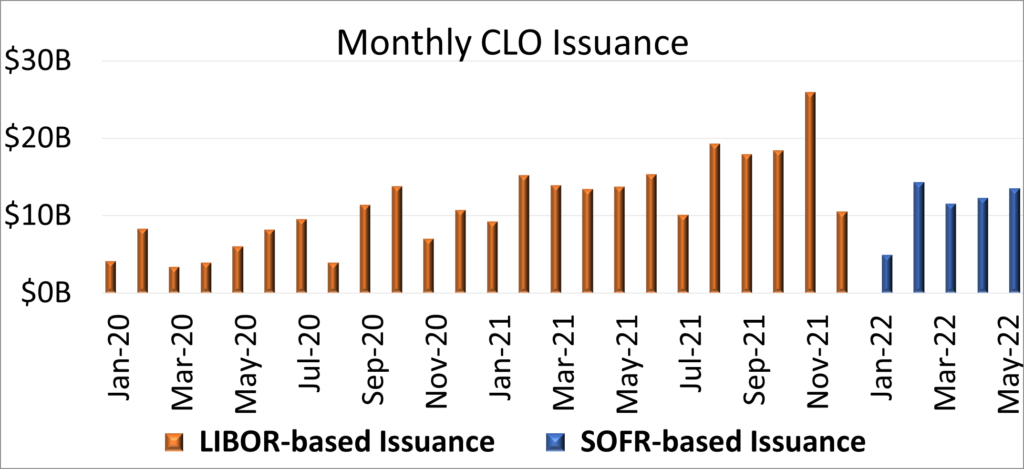

The mechanics of the new SOFR-based institutional syndicated loans impact not only the regulated bank institutions (which are typically the parties that act as lead arranger and administrative agent of the credit facilities), but also institutional lenders (typically collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) and Debt Funds that become lenders under the credit facilities and are interested in trading the loans efficiently). Like the regulated banks, which are largely responding to the Regulators’ Joint Statements in moving credit facilities they help arrange away from LIBOR, the institutional lenders also appear to be eager to move to the new SOFR-based lending world. From statistics provided by Refinitiv (a graph representing these statistics is reproduced below), almost all the CLO notes issued in 2021 referenced LIBOR but almost all the CLO notes issued in 2022 reference SOFR.

As the market for SOFR-based credit agreements has continued to evolve over the course of the first half of 2022, market participants (lead arrangers, administrative agents, lenders, and borrowers) have continued to explore issues that are affected by the new SOFR-based credit agreements. Among specific topics of interest, participants have focused on:

- the variance among the non-LIBOR referencing syndicated credit agreements (Term SOFR vs. Daily Simple SOFR vs. BSBY vs. any other credit sensitive rates);

- interest rate benchmarks used for incremental facilities in legacy deals;

- credit spread adjustments in newly originated credit agreements;

- interest period variations;

- trading mechanics of SOFR-based loans; and

- LIBOR remediation and what impact the new SOFR-based credit agreements may have on Early Opt-in Elections and refinancing/repricings of existing LIBOR loans.

We briefly discuss the latest developments in each of these areas of focus below.

(i) Variance in Interest Rate Benchmarks

Because the Regulators have only encouraged the transition away from LIBOR, a number of interest rate benchmarks have arisen as potential replacements for LIBOR in loan agreements.

The most prominent of such benchmarks is SOFR, which stands for the Secured Overnight Financing Rate. SOFR has been recommended by the Alternate Reference Rates Committee (the “ARRC”)[8] as its preferred alternative reference rate since June 22, 2017.[9] Unlike LIBOR, SOFR is an overnight rate and in its pure form can present operational challenges for certain regular loan market activities, such as prepayments and loan trading. Therefore, SOFR’s use as Daily Simple SOFR in credit agreements has mostly been limited to bilateral or pro rata investment grade facilities that do not normally trade.

A related benchmark, which offers a forward-looking term rate (just as LIBOR is), is Term SOFR. Term SOFR rates “provide an indication of the forward-looking measurement of overnight SOFR, based on market expectations implied from derivatives markets.”[10] CME Group publishes Term SOFR for interest periods of one month, three months, six months and 12 months, and each of CME Group’s rates have been formally recommended by the ARRC for use as replacement rates to LIBOR.[11] Due to the forward-looking nature of Term SOFR rates and the fact Term SOFR has the same operational characteristics as LIBOR, Term SOFR has been the most widely used benchmark in the new syndicated loan agreements that have closed since the beginning of 2022. The same rate has been used in CLO issuances as well.

Other SOFR-based variations are available, such as SOFR compounded in advance using the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s 30-, 90- and 180-day averages or SOFR compounded in arrears; however, these rates have not received widespread usage in the U.S. syndicated loan market.

Certain other potential benchmarks have been developed as potential replacements to USD LIBOR. These benchmarks all have in common the inclusion of a “credit sensitive component,” which more closely mirrors LIBOR in a time of credit stress. The most prominent of the credit sensitive rates are the Bloomberg Short Term Bank Yield Index (“BSBY”) and the American Interbank Offered Rate (“Ameribor”). Each rate is calculated using a proprietary formula and includes a means of capturing bank credit spreads. While the credit sensitive rates more closely resemble LIBOR than either SOFR or Term SOFR, none of them have been formally recommended by the ARRC and they are also not used as fallback or originating benchmark rates in CLO issuing indentures. As a result, there has been a comparatively low inclusion of such rates in broadly syndicated loan agreements. The credit sensitive rates are most likely to be used in certain regional U.S. bank bilateral or pro rata club syndicated transactions.

Lastly, especially in the first quarter of 2022, there were a few transactions that still used USD LIBOR at origination. These transactions were usually either (i) transactions evidenced by credit agreements that became effective in 2022 but were already committed before the start of 2022; or (ii) “fungible” incremental facilities to existing USD LIBOR credit agreements.

(ii) Interest Rate Benchmarks Used for Incremental Facilities in Legacy USD LIBOR Credit Agreements

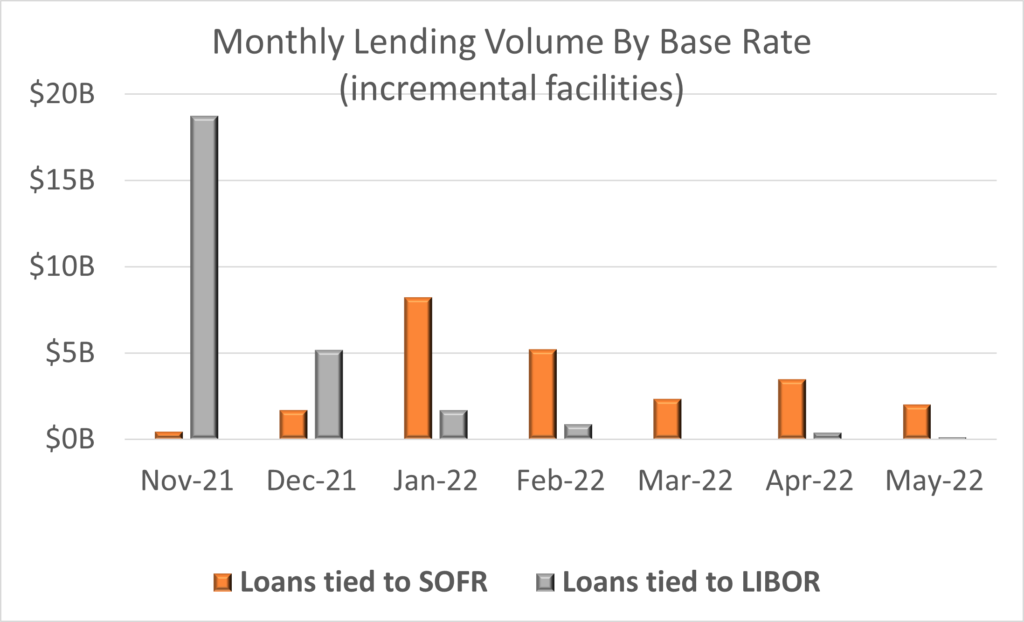

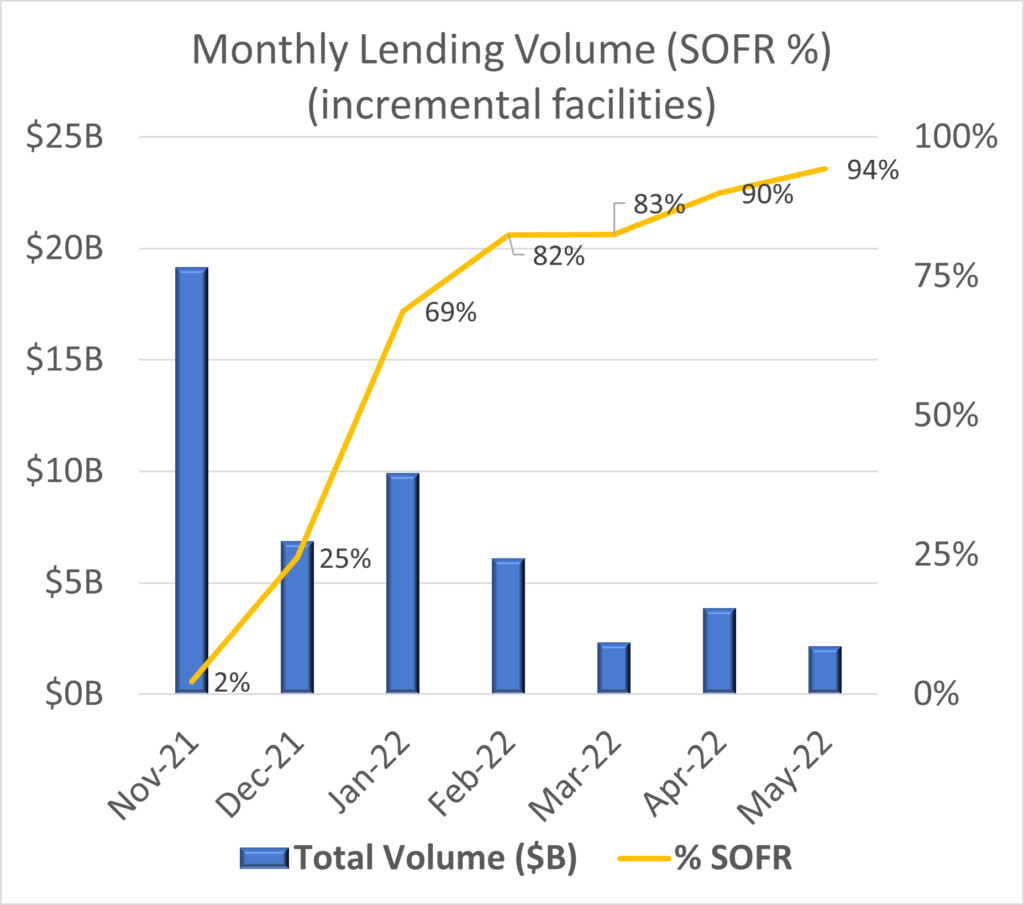

During the first quarter of 2022 there were a minority of incremental facilities (also referred to interchangeably as accordions or add-ons) that were originated using USD LIBOR. From statistics provided by LevFinInsights (graphs representing these statistics are reproduced below), the pivot from LIBOR to SOFR in incremental facilities has been somewhat less drastic than in newly originated credit facilities, although a large majority still use SOFR rather than LIBOR.

While an incremental facility is viewed by many to fit squarely into the definition of a “new contract” used in the 2021 Statement, there are perhaps a few reasons why the use of USD LIBOR in incremental facilities is a “gray” area, especially for those incrementals that were originated in the early part of 2022.

First, incremental facilities are usually much smaller in size than the existing credit facility that exists in the original credit agreement. Given this, it is advantageous and sometimes essential that the new incremental loan be “fungible” with and trade together with the existing credit facility. Without fungibility, given the smaller size, it would be difficult to ensure liquidity in the incremental loan, and the ultimate impact is likely to be a higher interest rate charged to the borrower. The new incremental loan would not be fungible if it uses a SOFR-based interest rate while the existing credit facility continues to use a LIBOR-based interest rate. While an obvious answer may be to amend or refinance the entire credit facility, that is not feasible for all borrowers and can lead to much greater overall transaction costs. With this in mind, one argument that can be made for a LIBOR-based incremental loan is that such a LIBOR origination prevents a disruption to the leveraged loan market with respect to those borrowers that would incur increased transaction costs, and thus complies with the overall goal of regulators not to disrupt the market during LIBOR transition.

Another argument that can be made is that an incremental facility ultimately uses the same loan documentation as the original credit agreement. As such, the new incremental loans would switch from LIBOR to a replacement rate at the same time that the original credit agreement would switch pursuant to its LIBOR replacement mechanics. The new incremental loan would not require a separate amendment to achieve the transition of the entire facility.

Finally, some in the market have taken the position that an incremental facility is not a “new contract,” as the mechanics for the increase are contained in the existing loan agreement. In other words, the borrower is just activating a provision in their loan agreement that already exists, and therefore the requirement to move to USD LIBOR is not required pursuant to the 2021 Statement.

(iii) Credit Spread Adjustments in Newly Originated Credit Agreements

The size of the credit spread adjustment has been the most contentious and heavily negotiated term in SOFR-originated credit agreements. While SOFR is a rate that broadly measures the cost of borrowing cash overnight collateralized by Treasury securities,[12] LIBOR is a rate that averages the rates at which large banks could fund themselves on the wholesale, unsecured funding market.[13] Due to the unsecured nature of the transactions that LIBOR measures, the LIBOR rate is generally higher than SOFR; additionally, LIBOR historically has had larger upward fluctuations in times of economic stress. To capture the difference between the rates over different interest periods (e.g., one month, three months), both the ARRC and ISDA recommended the use of a five-year median spread adjustment,[14] which compares the median LIBOR and Compounded SOFR figures over the five-year period from March 2016 to March 2021. The exact amounts that should be added to one-month, three-month and six-month SOFR contracts (whether of the Daily Simple, Daily Compounded, or Term SOFR variety) using this method are 0.11448%, 0.26161%, and 0.42826%, respectively.[15] These amounts will be added in all contracts that transition from LIBOR to Term SOFR or Daily Simple SOFR relying on the ARRC hardwired fallback mechanics or pursuant to the federal Adjustable Interest Rate (LIBOR) Act.[16]

While it would be consistent to have newly originated SOFR credit agreements use the same credit spread adjustments as will be used for fallback purposes, there is no requirement on market participants to do so. The most recent data shows that switching from LIBOR to Term SOFR plus the ARRC and ISDA recommended credit spread adjustment would lead to a very slightly lower interest rate for borrowers that use one-month interest periods to borrow, while borrowings of three-month and six-month interest periods would result in larger increases to interest rates. The interest rate savings on one-month interest periods are especially modest when considering that due to the rising interest rate environment, more borrowers are likely to choose longer interest periods in order to “lock in” their interest rate for a longer period. However, as both LIBOR and Term SOFR move differently, the differences between these rates (and whether LIBOR or Term SOFR adjusted by adding the ARRC and ISDA recommended credit spread adjustments results in a higher or lower interest rate) fluctuates regularly.

The below table illustrates recent data by showing a “point in time” comparison as of June 23, 2022, between LIBOR, Term SOFR, and Term SOFR adjusted by adding the ARRC and ISDA recommended credit spread adjustments.

June 23, 2022, Comparison of LIBOR, Term SOFR, and Adjusted Term SOFR

LIBOR | Term SOFR | Term SOFR + ARRC/ISDA CSA | |

1 month | 1.62357% | 1.49738% | 1.61186% |

3 months | 2.19729% | 2.01322% | 2.27483% |

6 months | 2.83529% | 2.56366% | 2.99192% |

From the start of 2022, the newly originated SOFR-based credit agreements have included a mixture of different credit spread adjustments. On one side of the spectrum there are credit agreements that do not appear to add any credit spread adjustment to the Term SOFR rates.[17] On the other side of the spectrum, some credit agreements have adopted the ISDA- and ARRC-recommended credit spread adjustments. The other two most popular options picked by market participants are: (i) adding a flat 0.10% credit spread adjustment across all interest periods; or (ii) adding 0.10%, 0.15%, and 0.25% credit spread adjustments for one-month, three-month, and six-month interest periods respectively. The flat 0.10% credit spread adjustment is more frequently adopted in investment grade or other “pro rata” credit facility agreements that are largely not traded in the secondary loan market. The formulation that includes 0.10%, 0.15%, and 0.25% credit spread adjustments for one-month, three-month, and six-month interest periods respectively is more frequently adopted in leveraged loan credit facility agreements than investment grade credit facility agreements. It is worth noting that if we reference the June 23, 2022, data, both the flat 0.10% and the 0.10%, 0.15%, and 0.25% credit spread adjustment formulations would lead to lower interest rates for borrowers across each of one-month, three-month, and six-month interest periods.

It remains to be seen if, after the LIBOR transition period has ended, some credit agreements will continue to reference a credit spread adjustment to SOFR or whether margin pricing will simply evolve to take into consideration a SOFR benchmark instead of a credit sensitive benchmark.

(iv) Interest Period Variations

The ARRC endorsement of the 12-month CME Term SOFR rate on May 19, 2022[18] resolves one of the open questions of whether or not parties to a credit agreement could include a 12-month interest period. The remaining interest periods that are frequently included in LIBOR-based credit agreements but are not published by the CME as Term SOFR interest periods are one-week and two-month term rates.

With respect to a two-month interest period, we have not seen SOFR-originated credit agreements that include this interest period. For those credit agreements that originated using LIBOR and included a two-month interest period, administrative agents could interpolate the two-month interest period rate using the published one-month and three-month LIBOR rates if permitted pursuant to the terms of the credit agreement.[19] Those credit agreements that contain certain ARRC-based LIBOR transition mechanics allow the administrative agent to remove the two-month interest period. The earlier credit agreements that did not include such a mechanic are still likely not to include the two-month interest period in the LIBOR transition amendment agreed by the parties. Many administrative agents have already notified borrowers that two-month interest periods are not available under their facilities as of the end of 2021.

With respect to the one-week interest period, there have been a few SOFR-originated credit agreements that have retained a quasi-one-week interest period. The most common alternatives used in the market either allow the borrower to make interest payments weekly using the Daily Simple SOFR rate or use the one-month Term SOFR published rate as the reference for the one-week interest period.[20] Failing these mechanics, a borrower could still prepay and reborrow the loan on a weekly basis, but this option can only be used in revolving credit facilities and the borrower risks incurring breakage costs as well as having to remake the representations and warranties in the credit agreement each week upon the new drawing. For LIBOR-based credit agreements, the ability to interpolate a one-week LIBOR rate will depend on the wording of any interpolation mechanics. The results are likely to be similar as with respect to the two-month interest period with the one-week interest period most frequently dropped.

(v) Trading Mechanics of SOFR-Based Loans and the Secondary Trading Market

Historically, secondary trading of loans in the institutional market has been evidenced using the LSTA forms of Confirmation (whether the LSTA Distressed Trade Confirmation or the LSTA Par/Near Par Trade Confirmation), and recently a similar form has been developed by the LSTA for primary allocations (the LSTA Primary Allocation Confirmation) (collectively referred to as “LSTA Trade Confirmations”). Each of the LSTA Trade Confirmations incorporates a Standard Terms and Conditions document that, among other terms, includes a concept for when and how interest on a loan that is earned by a lender may be passed to a prospective lender during the period of time that passes after the parties have agreed to trade the loan but before such loan trade has settled. This concept includes a defined term for “Cost of Carry,” which has historically used LIBOR to calculate what is owed among the parties.

As noted above, since the start of 2022, both new syndicated credit agreements that evidence the loans that are being traded, as well as the indentures that evidence the notes that are used by the institutional lenders to fund themselves, are using SOFR to calculate interest. In line with this move to SOFR, the LSTA updated the LSTA Trade Confirmations and related Standard Terms and Conditions on December 1, 2021, to reference Daily Simple SOFR instead of LIBOR. This change more closely aligns the secondary trading documents with the relevant credit agreements.

(vi) Remediation of Legacy LIBOR Credit Agreements

On March 5, 2021, the Financial Conduct Authority (the “FCA”) announced the future cessation or loss of representativeness dates for the 35 LIBOR settings published by the ICE Benchmark Administration.[21] The two key dates in the announcement were December 31, 2021 (after which all the interest period tenors for GBP, EUR, JPY and CHF LIBOR and the one-week and two-month interest period tenors for USD LIBOR either cease or lose representativeness), and June 30, 2023 (after which the remaining USD LIBOR interest period tenors would cease or lose representativeness).

The immediate impact of the March 5, 2021, FCA announcement was that a trigger in the ARRC-based LIBOR replacement mechanics was met and that all agreements referencing non-USD currency LIBOR rates should have been replaced or amended by December 31, 2021. As a result, the fourth quarter of 2021 included a lot of LIBOR replacement amendment activity with respect to the non-USD currency LIBOR rates. Some credit agreements referencing non-USD currency LIBOR rates were not immediately amended but instead a “suspension of rights” letter was delivered by the borrower in those credit facilities that acknowledged and agreed that the borrower would not borrow the non-USD currency loans until such time as the non-USD currency LIBOR rates were replaced.

With the non-USD currency LIBOR loans generally remediated, the focus from the beginning of this year and through June 30, 2023, shifts to USD LIBOR loans. The first six months of 2022 have seen a number of existing USD LIBOR loans remediated to SOFR through “organic” means such as refinancings or repricings. In those cases, given that either new lenders provide the financing that refinances the existing credit facility or 100% of the existing lenders have to vote to amend the agreement, the fallback mechanics of the existing credit agreement are irrelevant, and parties may negotiate and agree to their preferred benchmark rates, credit spread adjustments, etc. A primary purpose of the extension of the USD LIBOR cessation date of most tenors from December 31, 2021, to June 30, 2023, was to allow a greater portion of facilities to naturally transition to reduce the number of outstanding contracts which had no or inadequate fallback language.

The ARRC has recommended that, where feasible and appropriate to the circumstances, parties remediate their contracts ahead of USD LIBOR cessation.[22] These proactive remediation efforts, rather than relying on the mechanics of the fallback language, may have a number of benefits for parties. We have not seen a great deal of consensual USD LIBOR replacement amendments to date. However, it is generally expected that this replacement process will increase in velocity through the second half of 2022 and into 2023, although that velocity will presumably be impacted by the then-current interest rate environment and how incentivized a borrower is to transition from USD LIBOR.

On June 21, 2022, the LSTA released different forms of benchmark replacement amendments that may be used by the market participants as they remediate their legacy USD LIBOR credit agreements. The forms are drafted to provide for either: (i) a “golden amendment” that contains in it all the relevant SOFR-based terms and definitions and is meant to apply to any type of credit agreement, no matter what defined terms of which sections of the existing credit agreement contains the relevant LIBOR provisions that are replaced; or (ii) a “cover amendment” with an annex, which is meant to be a redline of the existing credit agreement that shows the changes made to the agreement to replace LIBOR with SOFR (whether Term SOFR or Daily Simple SOFR). The advantage of using the “golden amendment” form is that the transaction costs for amending the credit agreement are much lower as the same form may be used for many credit agreements. However, a future amendment and restatement of that credit agreement may prove more challenging, as might properly cross-referencing sections in related loan documentation. As for the “cover amendment” with redline approach, the upfront costs of amending would be higher as each amendment is bespoke and follows the existing credit agreement. However, it is easier down the line to amend the agreement again and/or to follow where the new provisions are in the agreement.

This article is based on a CLE program that took place during the ABA Business Law Section’s Hybrid Spring Meeting 2022. To learn more about this topic, view the program as on-demand CLE, free for members.

https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/files/bcreg20201130a1.pdf ↑

See id. ↑

See id. ↑

See id. ↑

https://www.federalreserve.gov/supervisionreg/srletters/SR2117a1.pdf ↑

See id. ↑

See id. ↑

The ARRC is a group of private-market participants convened by official sector agencies to identify a set of alternative U.S. dollar reference interest rates and to identify an adoption plan with means to facilitate the acceptance and use of these alternative reference rates. ↑

https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/microsites/arrc/files/2017/ARRC-press-release-Jun-22-2017.pdf ↑

https://www.cmegroup.com/market-data/cme-group-benchmark-administration/term-sofr.html ↑

See https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/Microsites/arrc/files/2021/ARRC_Press_Release_Term_SOFR.pdf, with respect to one-month, three-month, and six-month Term SOFR, and https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/Microsites/arrc/files/2022/ARRC_CME_12-Month_SOFR_Term_Rate.pdf with respect to 12-month Term SOFR. ↑

https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/Microsites/arrc/files/2020/ARRC_Recommendation_Spread_Adjustments_Cash_Products_Press_Release.pdf ↑

https://assets.bbhub.io/professional/sites/10/IBOR-Fallbacks-LIBOR-Cessation_Announcement_20210305.pdf ↑

https://rules.house.gov/sites/democrats.rules.house.gov/files/BILLS-117HR2471SA-RCP-117-35.pdf ↑

Note, it is often unclear whether the parties negotiated to have no credit spread adjustment in these agreements or whether a credit spread adjustment has been added to the applicable margin. The LSTA credit agreement forms adopt a more transparent formula where the credit spread adjustment would be specified as an adjustment in the “Adjusted Term SOFR” or “Adjusted Daily Simple SOFR” definitions. ↑

https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/Microsites/arrc/files/2022/ARRC_CME_12-Month_SOFR_Term_Rate.pdf ↑

Note: one-week and two-month LIBOR rates ceased to be published after 2021. ↑

While the one-month Term SOFR rate likely is higher than a one-week Term SOFR rate would have been, using this approach simplifies the calculations of the administrative agent and borrower in determining interest owing at the end of the one-week period. ↑

https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/documents/future-cessation-loss-representativeness-libor-benchmarks.pdf ↑

The ARRC’s LIBOR Legacy Playbook published on July 11, 2022, https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/Microsites/arrc/files/2022/LIBOR_Legacy_Playbook.pdf ↑