I. Introduction

Suppose your client has a judgment from a court in state X against a shareholder of a closely held corporation organized under the law of state X. You know that your client can levy on the judgment debtor’s shares to enforce the judgment and either obtain the shares (and attendant voting and economic rights) or trigger a pre-existing buy-out agreement with the shareholders or the corporation, which will replace the judgment debtor’s shares with right to payment. The relevant civil procedures may be complicated (or even arcane), but in theory your client’s remedy is straightforward.

Now suppose that the judgment debtor is a member of a limited liability company organized under the law of state X. Your client may not levy on the debtor’s membership interest and, moreover, has no right under any circumstances to acquire or dispose of any governance or information rights associated with the membership. A charging order, which “constitutes a lien on a judgment debtor’s transferable interest and requires the limited liability company to pay over to the person to which the charging order was issued any distribution that otherwise would be paid to the judgment debtor,” is “the exclusive remedy by which a person seeking in the capacity of judgment creditor to enforce a judgment against a member or transferee may satisfy the judgment.” ULLCA (2013) § 503(a), (h). (The rights of a secured creditor are an entirely separate matter. For an introduction to the complex interaction between Uniform Commercial Code, Article 9 and the “pick your partner” principle, see a recent article by Carl S. Bjerre, Daniel S. Kleinberger, Edwin E. Smith, and Steven O. Weise.

This column provides an introduction to the charging order, a remedy that is abstruse, arguably arcane, and in effect as much a remedy limitation as a remedy. Part II explains the origins and rationale for the charging order and its status as the “exclusive remedy.” Part III, written for a “charging order neophyte,” (i) describes the mechanics of charging orders, and (ii) discusses how the charging order differs from ordinary post-judgment remedies in two important ways. Part IV lists a number of difficult, open issues pertaining to charging orders. Part V explains why a business lawyer should care about the charging order and offers a suggestion for proactive lawyering. Part VI concludes by identifying two excellent resources for further information. Almost all the observations in this column apply equally to charging orders pertaining to general and limited partnership; however, for simplicity’s sake, this column refers solely to limited liability companies and members.

II. Origins of the Charging Order as a Remedy and Remedy Limitation

All U.S. charging order statutes derive from the English Partnership Act of 1890, which sought to protect the property of a partnership from judgment creditors of a partner. As explained in an article written back in 2004 (when the charging order was just beginning its journey toward notoriety among LLC and partnership practitioners in the U.S.):

The protection was necessary because of the then prevailing “aggregate” view of a partnership and the resulting confusion over the rights of partners (and their separate creditors) in partnership property. Under the aggregate view, the firm was not a juridical person, had no legal status separate from its individual members, and could not own property in its own right. Firm assets were therefore seen as owned by the partners collectively. This construct made life complicated enough when a creditor of the partnership sought to levy on the partnership assets. When a creditor of a partner took action against partnership assets, the result was often chaos.

Daniel S. Kleinberger, Carter G. Bishop & Thomas Earl Geu, Charging Orders and the New Uniform Limited Partnership Act Dispelling Rumors of Disaster, Prob. & Prop., July/Aug. 2004, at 30, 31.

An English case, decided in 1876, described the chaos as follows:

When a creditor obtained a judgment against one partner and he wanted to obtain the benefit of that judgment against the share of that partner in the firm, the first thing was to issue a [writ of execution], and the sheriff went down to the partnership place of business, seized everything, stopped the business, drove the solvent partners wild, and caused the execution creditor to bring an action in Chancery in order to get an injunction to take an account and pay over that which was due by the execution debtor. A more clumsy method of proceeding could hardly have grown up.

Brown, Janson & Co. v. A. Hutchinson & Co., 1895 Q.B. 737 (Eng. C.A.) (Lindley, J.).

The original, 1914 version of the Uniform Partnership Act adopted the English charging order statute essentially unchanged. The Revised Uniform Partnership Act (RUPA), promulgated in its final from in 1997, refined the charging order language somewhat but left essentially unchanged the construct and its mechanics. The latter point is noteworthy because RUPA eliminated the original, aggregate-based rationale for the charging order construct. RUPA section 201(a) proclaims, “A partnership is an entity distinct from its partners,” and the 1997 official comment describes “the entity theory as the dominant model” for the act and characterizes the act as “embrac[ing] the entity theory of the partnership.”

Nonetheless, a charging order provision is part of partnership law throughout the United State, including the more than 35 jurisdictions that have adopted RUPA. Moreover, every LLC statute contains a charging order provision, even though no one has ever doubted that a limited liability company is an entity and not an aggregate.

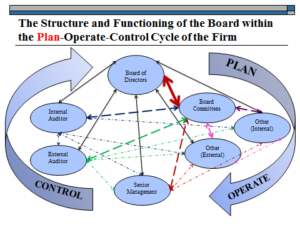

The official comment to ULLCA (2013), section 503(f) explains why the charging order construct has outlived its original rationale: “The charging order remedy—and, more particularly, the exclusiveness of the remedy—protect the ‘pick your partner’ principle.” According to that principle, absent a contrary agreement among the members, no person may become a member or obtain a member’s governance or information rights in the limited liability company without the unanimous consent of the members. The transfer restrictions built into every LLC statute form the principle’s primary bulwark. For example, using language dating back to 1914, the New York LLC Act provides that: “an assignment of a membership interest does not … entitle the assignee to participate in the management and affairs of the limited liability company or to become or to exercise any rights or powers of a member.” NY LLC Act, § 603(a)(2). The Uniform LLC acts use a more modern approach, which RUPA initiated. “Transferee” replaces “assignee” and “a transfer, in whole or in part, of a transferable interest . . . does not entitle the transferee to: (A) participate in the management or conduct of the company’s activities and affairs; or (B) . . . have access to records or other information concerning the company’s activities and affairs.” ULLCA (2013) § 502(a)(3).

Under the uniform acts, the definition of “transfer” would make these general restrictions applicable against a judgment creditor seeking to levy on a membership interest. ULLCA (2013) § 102(23)(g) (defining transfer to include “a transfer by operation of law”). As the exclusive remedy, however, the charging order construct goes much further. The construct prohibits any levy (even on the judgment debtor’s economic rights) and confines the judgment creditor to a lien on any company distributions otherwise due the debtor. (The explanation for the harsher treatment of involuntary creditors may be that an operating agreement can further protect “the pick your partner” principle against voluntary transfers of economic rights, but cannot affect the rights of judgment creditors. See Daniel S. Kleinberger’s article on transfer restrictions.

III. Charging Order Mechanics and the Departure from the Remedies Norm

Whether the mechanics of charging orders seem odd at first glance to a “charging order novice” depends on whether the novice is at least somewhat familiar with ordinary procedures for enforcing a judgment. If she or he is, the charging order seems at best a “peculiar mechanism.” Jay David Adkisson, Charging Orders: The Peculiar Mechanism, Dec. 1, 2016, and the mechanism’s departure from the remedies norm will likewise seem peculiar.

Obtaining, Complying With, Contesting, and Enforcing a Charging Order

To enforce a judgment against a person’s ownership interest in a limited liability company, the judgment creditor must apply to the appropriate court for an order charging the judgment debtor’s interest in the company, i.e., directing the company to divert to the judgment creditor any distributions otherwise due the debtor-member (including liquidating distributions and payments to redeem any or all of the debtor’s interest). The statutory language, although scant, is well understood to contemplate a hearing. What is not clear is to whom the judgment creditor must give notice: to the judgment debtor because the charging order is after all a post-judgment proceeding; to the company because the order, if issued, will directly affect the company; or to both? (The answer is uncertain. See Part IV.) In most instances, the hearing should be largely pro forma, assuming the applicant provides documentation of the judgment and shows a basis for believing the debtor has an interest in the company and neither the judgment debtor nor company disputes those issues or the court’s jurisdiction. (Jurisdiction is a complex issue. See Part IV.)

Once issued, a charging order must be served on the company (as with any other order applying to a person). A limited liability company that makes a distribution to the judgment debtor in violation of a charging order risks not only a contempt of court citation, but also a turnover order, i.e., an order requiring the company to pay the judgment debtor the same amount paid previously to the judgment debtor.

However, even with a charging order in place, the judgment creditor has no assurance of collecting on the judgment. The limited liability company might have no funds with which to make distributions, or those managing the company might not choose to make distributions, whether for legitimate or nefarious reasons. So, under the uniform acts and the laws of most states, an additional remedy is available: “Upon a showing that distributions under a charging order will not pay the judgment debt within a reasonable time, the court may foreclose the lien and order the sale of the transferable interest.” ULLCA § 503(c).

The foreclosure remedy is itself “a peculiar mechanism.” Formally, the foreclosure results in a judicial sale, and “the purchaser at the foreclosure sale obtains only the transferable interest” of the judgment debtor, id., i.e., the right to receive whatever distributions the judgment debtor would otherwise have been entitled to receive. However, why would someone pay for a payment right equivalent to the charging order lien when a court has just concluded that the payment right is more like a dry creek bed than a reliable income stream? Moreover, unlike the holder of a charging order, an owner of an economic interest in a limited liability company is considered a partner for income tax purposes and is therefore liable for an aliquot portion of an LLC’s annual profits even if not a penny is actually distributed. Carter G. Bishop & Daniel S. Kleinberger, Limited Liability Companies: Tax and Business Law ¶ 8.07[1][a][ii] (Supp. 2018-2).

Despite this strong disincentive to foreclosure, several states have eliminated the additional remedy. See, e.g., Ala. Code 10A-5A-5.03. “This section [on charging orders] provides the exclusive remedy by which a judgment creditor of a member or transferee may satisfy a judgment out of the judgment debtor’s transferable interest and the judgment creditor shall have no right to foreclose, under this chapter or any other law, upon the charging order . . . or the judgment debtor’s transferable interest.”). Delaware has gone even further. Del. Code Ann. tit. 6, § 18-703(d) provides:

The entry of a charging order is the exclusive remedy by which a judgment creditor of a member or a member’s assignee may satisfy a judgment out of the judgment debtor’s limited liability company interest and attachment, garnishment, foreclosure or other legal or equitable remedies are not available to the judgment creditor, whether the limited liability company has 1 member or more than 1 member.

(Emphasis added.) A remarkable exclusion in a state whose constitution mandates the existence of a court of chancery! Del. Const., art. 4, § 10. For some of the resulting complexities, see Part IV.

The Abnormalities

Although as described in Part IV the charging order remedy raises numerous particular issues, the remedy differs from other post-judgment collection remedies generally in two notable ways. The first is the need for an initial hearing; the second is the nature of the property subject to the remedy.

As to the first difference, typically the document that initiates the post-judgment process is either authored by the attorney for the judgment creditor or obtained from the court as a merely administrative matter. As to the second difference, usually (with the exception of wage garnishments) provisions on exempt property are found elsewhere than in the remedy statutes. In contrast, charging order statutes themselves turn a member’s governance and information rights into exempt property under state law.

IV. Difficult and Open Issues

The peculiarities of the charging order raise numerous troubling questions. Exploring them is beyond the scope of this column, but a list of brief descriptions is possible:

- Who must be given notice of the application for a charging order?

- What courts have jurisdiction to issue a charging order:

- the court that granted the judgment?

- the courts of the LLC’s state of formation?

- the courts of a state in which the LLC does significant business?

- the courts of the state in which the judgment debtor resides (if an individual) or has some important nexus (if an organization)?

- the courts of the state in which the membership interest (an intangible) is deemed to be present?

- How far may a court intrude into a limited liability company’s business and affairs to effectuate the charging order?

- How does the judgment creditor capture payments from the limited liability company to the judgment debtor, which the company characterizes as something other than distributions?

- What is the effect on the “exclusive remedy” provision, if:

- other law of the state appears to provide an alternative remedy?

- the judgment creditor uses the courts of one to levy on a membership interest pertaining to a limited liability company formed under the law of another state, especially if the LLC statute of the “levying” jurisdiction confines the jurisdiction’s charging order remedy and limitation to membership interests in domestic limited liability companies?

- In states that have eliminated the foreclosure remedy, may a court resort to equitable remedies if the lien turns out to be nothing but a dry creek bed?

- Suppose the charging order statute also precludes the courts of the state from exercising any equitable powers?

- Suppose the judgment debtor is the LLC’s sole member, so the pick-your-partner principle is inapposite?

- What happens to a charging order as exclusive remedy when the judgment debtor petitions for bankruptcy?

Given all these difficult and open issues, many experienced creditors’ rights attorneys disdain the charging order remedy, considering it more an inappropriate shield for judgment debtors than a useful tool for judgment creditors.

V. Why Should a Business Lawyer Care?

Obviously, a business lawyer who litigates should care about charging orders. Although winning a judgment is good, collecting is all important. However, lawyers who work with lenders should also care whenever a prospective borrower asserts an LLC membership interest as part of the person’s net worth. The charging order’s remedy limitation implies a substantial discount on the value of the membership interest as shown on a balance sheet. (Arguably at least, taking a security interest in the membership interest would decrease the discount, although as noted above, the interplay between “pick your partner” and UCC Article 9 is complex.)

For lawyers who form or counsel limited liability companies, the charging order is an opportunity for preventative law. Although the charging order constrains creditors, it nonetheless gives an outsider a stake in the company. The company can oust the outsider by paying the judgment; however, doing so is rarely attractive. The better course is to give the company an option to redeem any transferable interest subject to a charging order. The option price should not be confiscatory, but subject to bankruptcy law [a rather large exception], so long as the provision applies to all interest holders, the price can reflect a significant discount.

Such “call rights” are commonplace in well-counseled, closely held corporations. Unlike LLC statutes, corporate statutes (other than Nevada’s) have no built-in transfer restrictions. As a result, attorneys routinely draft contractual restrictions that inter alia prevent a judgment creditor (or purchaser at an execution sale) from acquiring a judgment debtor’s stock and becoming a full-fledged owner of the closely held business.

Thus, many examples exist for LLC practitioners seeking to draft call rights. In the context of a closely held corporation, the call right might belong to the corporation, the other shareholders, or both. The same approaches work just as well with limited liability companies.

VI. Conclusion

As indicated at the outset, this column is merely an introduction. Fortunately, for anyone interested in further information on this subject, the ABA Business Law Section recently published an extraordinary resource: Jay Adkisson, The Charging Orders Practice Guide: Understanding Judgment Creditor Rights Against LLC Members (ABA 2018). In addition, those interested in a national survey of the case law and state statutes on charging orders will find them at Carter G. Bishop & Daniel S. Kleinberger, Limited Liability Companies: Tax and Business Law ¶ 2.07[1][m][v]-[vi], Tables 2.1 (Charging Order Statutes) and 2.2 (State-by-State Table of Charging Order Cases).