In the aftermath of the widely-publicized control breakdowns at Wells Fargo Bank, and in a number of regulatory actions occurring this past year, boards of directors of public companies and financial institutions have been directed to improve oversight and corporate governance. Reacting to demands from regulators and shareholders to improve board oversight and governance, it seems that boards are evolving from an approach of focusing primarily on “tone at the top” to one of instituting substantive checks and balances and considering broader aspects of ethics, values and corporate culture.

In making this shift, boards not only oversee checks and balances being put in place, but also may take on direct responsibilities regarding the design of the checks and balances, especially checks and balances related to the CEO and other members of senior management. Because a number of reported ethics problems and failures in corporate controls have involved the senior-most executives, the responsibility for addressing these risks falls to a company’s board.

This article addresses the integration of board oversight and governance responsibilities along with what we believe to be the evolution from a focus on “tone at the top” to a focus on “checks and balances.” We also discuss the importance of ethics and values in corporate culture within the context of board governance.

Mandating Improved Board Oversight and Governance

Responding to widespread abuses in consumer sales practices and control breakdowns that occurred at Wells Fargo Bank over a period of several years, on February 2, 2018, the U.S. Federal Reserve Board announced consent and cease and desist orders requiring improvements in the firm’s governance and risk management processes, controls and board oversight. The orders included a restriction in the company’s growth until sufficient improvements are made. The public announcements of both the Fed and Wells Fargo confirmed the need for improvement, stating, “Within 60 days the company’s board will submit a plan to further enhance the board’s effectiveness in carrying out its oversight and governance of the company.” The Fed also criticized the job performance of the bank’s board and CEO in a press release, stating that the Fed “has sent letters to each current Wells Fargo board member confirming that the firm’s board of directors during the period of compliance breakdowns did not meet supervisory expectations. Letters were also sent to former Chairman and Chief Executive Officer John Stumpf and past lead independent director Steven Sanger stating that their performance in those roles, in particular, did not meet the Federal Reserve’s expectations.”

The Fed’s regulatory action expanded what many individuals and organizations have heretofore considered as a customary and general oversight responsibility to instead comprise a significant mandated obligation to institute procedures for enhanced oversight and governance. The action also required reporting on the same. This was no small step; however, the view that a fundamental responsibility of a governing board is to govern is not new. Retired Delaware Supreme Court Chief Justice E. Norman Veasey, in his Pennsylvania Law Review article of May 2005, stated that stockholders should have the right to expect that “the board of directors will actually direct and monitor the management of the company, including strategic business and fundamental structural changes.” Further to the point that directors have management as well as oversight responsibilities, retired Delaware Chancery Court Chancellor William B. Chandler also stated in his opinion in the 2003 Disney shareowner derivative suit, “Delaware law is clear that the business and affairs of a corporation are managed by or under the direction of its Board of Directors. The business judgment rule serves to protect and promote the role of the board as the ultimate manager of the corporation.” In a discussion of internal controls and director responsibilities on the Federal Reserve website, the Fed describes a board’s responsibility to create and enforce prudent policies and practices with the following statement: “Directors are placed in a position of trust by the bank’s shareholders, and both statutes and common law place responsibility for the affairs of a bank firmly and squarely on the board of directors. The board of directors of a bank should delegate the day-to-day routine of conducting the bank’s business to its officers and employees, but the board cannot delegate its responsibility for the consequences of unsound or imprudent policies and practices.”

Boards seeking to address expectations for enhanced oversight and governance face many challenges, among them a lack of definition of what constitutes “effective governance” in organizations. Economists have long recognized that the division of labor of a firm is specific to a firm at a point in time. Similarly, there is no single standard and no single metric for what constitutes effective governance—no common best practice, no “one size fits all” approach to follow. Just as the division of labor in an organization is unique to each organization and to each point in time, effective governance is necessarily both organization-specific and time-specific. Models and practices are useful sources of information to consider in designing governance and control structures, but there is no off-the-shelf, “one best way” for any organization. What is needed in an organization will inevitably change over time, sometimes unexpectedly and rapidly in response to a crisis or other change in circumstances.

The “Principles of Corporate Governance,” issued by the Business Roundtable (BRT), an organization of the CEOs of America’s leading companies, is one document that speaks to this reality. The following is a short excerpt from the most recent update of the Principles, issued in 2016:

“In light of the evolving landscape affecting U.S. public companies, Business Roundtable has updated Principles of Corporate Governance. Although Business Roundtable believes that these principles represent current practical and effective corporate governance practices, it recognizes that wide variations exist among the businesses, relevant regulatory regimes, ownership structures and investors of U.S. public companies. No one approach to corporate governance may be right for all companies, and Business Roundtable does not prescribe or endorse any particular option, leaving that to the considered judgment of boards, management and shareholders. Accordingly, each company should look to these principles as a guide in developing the structures, practices and processes that are appropriate in light of its needs and circumstances.”

The BRT’s Principles as well as other corporate governance references underscore the importance of each company’s senior management and board of directors devoting time and attention to designing structures, policies and processes that will provide effective governance in their organization’s unique situation. It is also important to examine and evaluate governance on an ongoing basis, especially as special events and circumstances arise. Mergers, acquisitions, takeover attempts, product failures, breakdowns in controls, lapses in ethical conduct—all these and other special conditions can arise at any time.

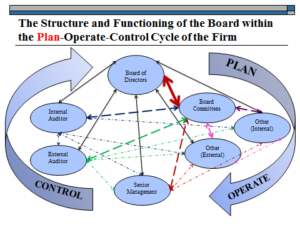

There is a very wide range of structures, functions, and players involved in considering a company’s governance and control system, as illustrated in the following diagram developed in H.S. Grace & Company’s services assisting senior management and boards of directors.

FIGURE 1

Figure 1 sets out the breadth of relationships which must be addressed by the board in formulating and activating effective corporate governance practices.[1] Once addressed, these relationships will require monitoring and updating.

Evolving from “Tone at the Top” to “Checks and Balances”

For the past several decades, corporate governance experts focused on an approach of improving the “tone at the top” out of a belief that a strong CEO setting the right tone was the best way to ensure good management practices and adequate controls throughout a company. But as failures occurred, at times involving CEOs who had ostensibly set “a right tone” in statements to employees and the general public, the limitations of such reliance became apparent. Now a distinct shift in approach is underway, focusing on a substantive set of checks and balances as essential in carrying out effective governance.

A substantive checks and balances approach addresses the roles, responsibilities, and relationships among the key elements and players in a firm’s governance, controls, and oversight system. Institutional investors, individual investors, and other market and regulatory interests increasingly demand that those involved in corporate governance recognize their responsibilities and are held accountable in addressing these responsibilities. An additional emerging expectation is that senior leaders in an organization, both board and management, recognize that a leader’s role is one of service rather than entitlement. Experience has shown that governing structures which consolidate power and authority into fewer and fewer hands, while conceptually attractive in terms of potential efficiency and effectiveness, often fail to meet conceptual ideals if individuals in power come to feel entitled to do as they please. Without effective oversight and a system of checks and balances, conditions are ripe for misconduct. In response to this reality, boards must not simply witness the implementation of the checks and balances, but also involve themselves in formulating the checks and balances and occupy active roles in the execution therein. Carrying out these active roles will necessarily lead to regular interaction with the CEO and others in senior management as well as with a company’s internal and external auditors. While tone at the top may sometimes remain only as words that do not actually affect behavior, the institution of checks and balances can exert considerable influence.

Careful inspection of what drives or underlies the effectiveness of successful organizations would indicate that over time they have put in place highly effective policies, procedures and controls. Individuals have well-defined responsibilities; the organizations make certain that individuals understand those responsibilities, and the organizations demand strict accountability. Individuals are expected to understand the organization’s mission and values and have an attitude of service. Moreover, there are well-understood consequences for falling short in discharging responsibilities, a clear measure of accountability.

Effective Governance Includes Ethics, Values, Corporate Culture

In addition to the structures, policies and processes that provide checks and balances, effective governance includes an organization’s ethics, values and corporate culture. Many problems in recent years have involved CEOs and other members of senior management. Much less often have board members been involved, but some instances of failures have occurred. Ethics problems can arise at any level; however, most corporate efforts at addressing ethical issues have seemed to involve developing broad programs for the entire organization, with limited attention being paid specifically to those at the top.

There are good business reasons to consider installing ethics programs for senior leaders—programs that are based on long-standing principles and that boards implement for themselves and senior management. In such an approach, the board would create a program and a set of expectations, then continue to monitor and periodically review the program, modifying where and when appropriate. Such programs integrate oversight and governance with ethics, values and corporate culture in a way that can enhance success of an organization.

A successful organization is attractive to prospective employees who will be the source of its intellectual capital. There is increasing recognition today that a firm’s most valuable asset is its intellectual capital. One need only look at the emergence and growth in value of innovative firms such as Google, Apple and WeWork to see evidence of the recognition accorded their intellectual capital. Although difficult to measure, intellectual capital is credited with significant portions of economic productivity increases and can play a critical role in the achievement and continuation of profitability in organizations. However, beyond the issues of profitability and monetary returns that have been traditionally sought by providers of financial capital and the owners of the physical components of production, the owners of intellectual capital —the skilled individuals who are “today’s professionals” — tend to seek to maximize their economic wellbeing via a combination of monetary and non-monetary compensation. Economic well-being is a broad concept that encompasses numerous factors affecting the overall quality of one’s life, as opposed to financial well-being, which considers only monetary compensation and the accumulation of wealth. One component of non-monetary compensation of interest to many of today’s professionals is a management culture based on ethics and values and respect, one that incorporates an attitude of responsibility, accountability, and service, as well as expertise and performance excellence.

The most effective managers of today’s intellectual capital and today’s professionals will be those who demonstrate a sense of responsibility, a willingness to be accountable, and an attitude of service. Today’s professionals tend to believe that “doing well” and “doing good” are not mutually exclusive, and that a combination of the two will result in the maximization of their individual economic well-being. Boards and management leaders who understand the difference between economic well-being and financial well-being and the complementary relationship between “doing well” and “doing good” are the most likely to be successful today. In contrast, management scenarios that are structured around entitlement or privilege are unlikely to be tolerated or sustainable. Intellectual capital is highly mobile, and individuals providing capital can exercise that mobility if management is not clear in its recognition of responsibilities, accountability, and an attitude of service.

It is interesting to note the research and insights of Robert Fogel, a Nobel laureate and one of the world’s leading economic historians. Fogel in his book, The Fourth Great Awakening: The Future of Egalitarianism in America (2000), discusses profound long-term trends in individual work habits. He points out that over the last 100 years there has been a considerable reduction in the time individuals spend in “earnwork” —that is, work associated with earning wages which in turn permits the acquisition of material possessions. He points out that what has increased is the time individuals spend in “volwork” —that is, personal time directed toward what he calls “non-material” and “spiritual” goods. Fogel found that individuals have consciously and deliberately made the decision to reduce the amount of “earnwork” and thus the material possessions they might otherwise acquire, and, instead have directed their time to family, community, religious, and other related activities. An important lesson for management that emerges from Fogel’s analysis is that as individuals seek to maximize their personal utility and personal satisfaction, not just to maximize their financial wealth, they become more cognizant of the activities from which their economic well-being springs. They see many more options and alternatives available to enable them to achieve an increased level of economic well-being. Today’s professionals look management directly in the eye. They call for management to have a comprehensive understanding of and a willingness to address responsibilities. They call upon management to be accountable, and to put in place appropriate sets of checks and balances for their own activities which will ensure accountability on the part of all the involved parties. Perhaps most importantly, they call for management to bring an attitude of service to leadership. Smart, well-trained, and mobile, today’s professionals will gravitate to working environments where management has their respect. The need for management to demonstrate an attitude of service is not surprising—one only has to recall that an attitude of service is a shared quality amongst the leaders from all walks of life who have been most widely revered and remembered.

Improving Oversight and Governance is Timely and Good Business

In furtherance of achieving and maintaining effective oversight and governance, and in the interest of earning the respect and loyalty of workers, the time is ripe for boards to focus on the ethics of management as well as the traditional focus on the ethics of the overall organization. It is both timely and good business for boards to put in place systems of substantive checks and balances that start with the CEO, senior management, and the board itself, and then proceed through the entire organization. Improving board and organizational oversight and governance can not only lower the risk of failures and problems in the organization, but can also bring sustainable operating benefits to a company and its shareholders.

[1] The authors, in their January 2018 BLT article, “Corporate Governance and Information Gaps: Importance of Internal Reporting for Board Oversight,” discuss the roles of internal reporting in corporate governance processes.