Most companies and the boards that govern them like to think their operations and supply chains are free of human rights abuses, yet of the 40 million estimated people enslaved worldwide, 16 million are working in forced labor within company operations and supply chains. Millions more work under dangerous and sometimes brutal conditions, toiling for up to 19 hours a day and subject to physical abuse at the hands of their supervisors. The eighth edition of the List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor and the 17th annual edition of the Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor published in September 2018 by the U. S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of International Labor Affairs (ILAB) highlight specific industry sectors in which child labor or forced labor persists. Abused workers can be found around the world, including within the United States. According to the human rights group Walk Free Foundation, an estimated 400,000 people are believed to be trapped in trafficking and modern slavery in the United States. If for no reason other than brand protection, there is a need for immediate proactive corporate initiatives in this context. To eradicate modern slavery, the C-suite must be encouraged by business lawyers to actively engage in supporting meaningful upstream and downstream change in identifying and remediating modern slavery.

The federal Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 (TVPRA), 18 U.S.C. §1589(a)(4) (originally enacted as Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act, Pub. L. No. 106-386, §112, 114 Stat. 1464, 1487 (2000)), defines labor trafficking as “the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for labor or services, through the use of force, fraud, or coercion for the purpose of subjection to involuntary servitude, peonage, debt bondage, or slavery.” 22 U.S.C. §7101(9).

The reality is that publishing a policy or two on the company website does not accomplish anything to tackle modern slavery or other abuses of labor standards. The growing development of legislative and investor focus on human rights issues is pushing larger companies to report on what, if anything, they are doing to tackle these problems at every tier of their supply chain. The United Kingdom’s Home Office estimates between 9,000 to 11,000 companies are required to report under the UK Modern Slavery Act alone. The reporting requirements recognize that modern slavery cannot be addressed without direct, private-sector participation. The work necessary for coordination of the efforts of the company’s internal legal, compliance, and procurement departments, however, can be daunting. Corporate resistance and real challenges encountered in drafting human rights policies and contract provisions, including greater exposure to the risk of litigation, must be addressed.

Human rights violations in the work force (including exorbitant recruitment fees and room and board fees, little to no pay, dangerous hourly demands, toxic exposure on the job site, and/or dangerous housing conditions, etc.) most often appear to involve the lower or lowest rung of a multi-tier international supply chain. Typically, this is the result of a breakdown in the company’s internal controls and due diligence processes. Red flags slip through the cracks and go unresolved, causing legal, financial, and reputational damage that cannot always be fully repaired. As more and more countries outside of the United States adopt laws to fight human rights violations, properly assessing the risk of human rights violations within the company’s supply chain and implementing an effective vendor risk-management program to assure compliance is essential to ensure that goods are not tainted by modern slavery, child labor, or other human rights violations.

The development of an enterprise-wide culture is essential, along with an understanding of, and commitment to, human rights (health and safety requirements, anti-forced labor, child labor, and indentured labor constraints). Supply chain mapping, integrated human rights due diligence, engagement with suppliers and workers, identification of root causes such as recruitment fees imposed on workers, and clear processes to remediate breaches when found are recognized as essential good practice if a company is trying to take their anti-slavery and worker abuse elimination seriously. Market-specific approaches must be identified and optimized.

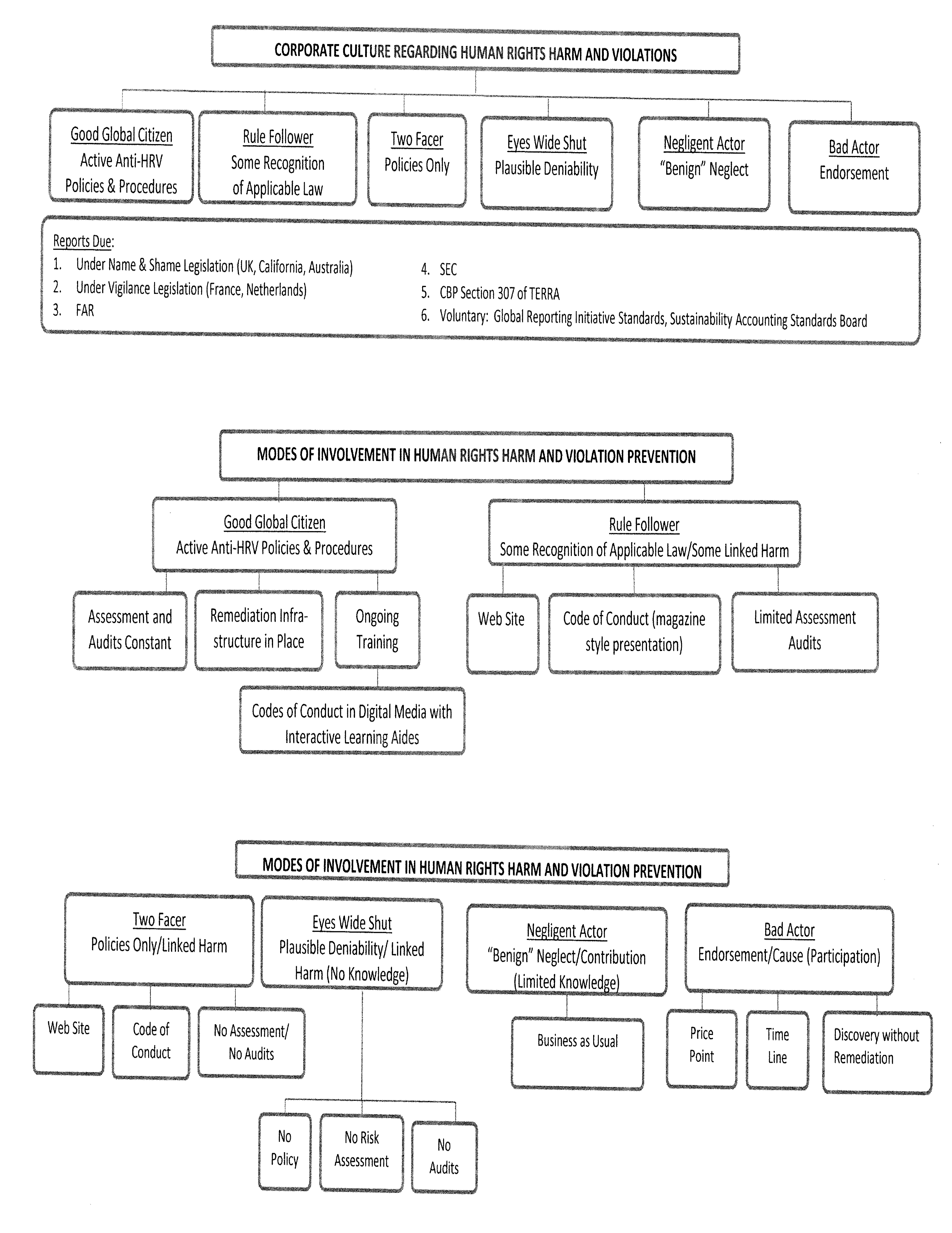

The following diagrams attempt to capture the possible spectrum of diverse corporate cultures in this context and the degree of responsibility undertaken to mitigate or remediate human rights abuses caused, directly or indirectly, by their activities.

The role of U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) to mitigate the risk of forced labor-produced goods from entering the United States under the Tariff Act of 1930, as amended by the Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015, should be recognized. The CBP has the authority to detain goods by issuing withhold release orders (WROs) at ports of entry if information reasonably, but not conclusively, indicates that merchandise is made with indentured, forced, or child labor. On September 30, 2019, CBP issued five WROs, effective immediately: garments produced by Hetian Taida Apparel Co., Ltd. in Xinjiang, China; disposable rubber gloves produced in Malaysia by WRP Asia Pacific Sdn. Bhd; gold mined in artisanal small mines in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo; rough diamonds from the Marange Diamond Fields in Zimbabwe; and bone black manufactured in Brazil by Bonechar Carvão Ativado Do Brasil Ltda. The Reasonable Care September 2017 publication from CBP and its extensive series of questions (pages 8–15) should be routinely referenced because those questions can be easily modified for use by any company serious about supply chain due diligence. The publication also provides a good road map of what CPB auditors look for in trying to determine whether imported goods are tainted by convict, forced, or indentured labor and informs of the kind of documentation CPB (or other governmental units) will ask a company to produce in any forced labor inquiry.

A November 2016 publication born out of a collaboration between the Global Compact Network Netherlands, Oxfam, and Shift entitled How to do business with respect for human rights is a guidance tool for companies that is also extremely helpful as a starting point resource. It is an introduction to the core concepts in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, and includes some practical steps to prevent, address, and remedy human rights abuses committed in business operations. Similarly, the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre has a number of reporting guidance resources, including The Modern Slavery Registry, to address and report on modern slavery in the context of a broader human rights due diligence. Verité, a civil society organization that promotes workers’ rights in global supply chains through research, consulting, training, assessments, and policy advocacy, has also published a number of research reports and white papers that can provide the information necessary to identify complex labor problems and design tools to address those problems. Offering assessment and training, Verité and other consultants work with governments and companies to develop policy and launch compliance initiatives.

Many companies, however, are still under the impression that there are not enough concrete tools to implement human rights policies. The Business Law Section’s Uniform Commercial Code Working Group (Working Group) published their “2018 Report and Model Contract Clauses for International Supply Contracts” in both the Fall 2018 issue of The Business Lawyer (Vol. 73, No. 4) and Business Law Today, November 28, 2018. The aim of the Working Group in drafting the Model Contract Clauses (MCCs) was to use the leverage of Western buyers and the legal force of contract documents to help eradicated forced labor and risks to worker health and safety by creating legally effective and operationally likely provisions. Since publication, there has been widespread interest in the MCCs, some movement toward adoption, and significant constructive feedback that the Working Group has embraced.

During the Business Law Section Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C., the Working Group, along with the Corporate Social Responsibility Committee’s Subcommittee to Implement the ABA Model Principles on Labor Trafficking and Child Labor, decided to use the next six months to a year to determine how best to incorporate in the MCCs much of the constructive feedback received since the initial publication in the Fall of 2018. The idea is to publish a version 1.1. One suggestion is to provide a further explanation of what is referred to in the MCCs as “the Schedule P strategy.” The idea of the Working Group was to encourage any company using the MCCs to incorporate into their supply chain contracts by attachment human rights policies the company developed specific to its industry and operations. Schedule P was to be another set of specifications the goods had to satisfy to be conforming. That is still the idea, but many found vague references to a Schedule P confusing and called for specific examples or references to policies like the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights or the ABA Model Principles on Labor Trafficking and Child Labor. Another recommendation is for the MCCs to address buyers’ role in the creation of human rights violations with unrealistic delivery targets, last-minute changes to orders, and low price point expectations. The addition of buyers’ representations and warranties within the MCCs has been suggested, along with reference to a “responsible buyer” code of conduct. Turning to the MCCs’ current emphasis on buyer’s termination rights upon discovery of defective goods (defined in the MCCs to include goods that were perfect in every way except for the abuse of human rights in their manufacture, distribution, or shipping), commentators since the MCCs’ publication propose an acknowledgment of buyers’ high switching costs in many industries and stress the benefits of remediation and specific performance as opposed to termination. These alternatives to termination, it has been argued, must be acknowledged as better for the workers as well as for the companies that employ and engage them. Each of these points is to be considered in preparing version 1.1 of the MCCs, along with the addition of an optional arbitration clause to address disputes.

Given the ethical, business, social, and moral issues that are implicated along with the ever-growing international legal requirements, commercial lawyers certainly now have an obligation to advise every business client with complex (multitier) operations of the variety of human rights abuses that may be hidden in their supply chains. The potential liability for exploitative labor practices (legal, moral, and social) require increased vigilance as well as thoughtful analysis of traditional confidentiality obligations and historic ownership of the attorney-client privilege. After discovery of a human rights violation in the audit or due diligence process, what reporting obligations does the discovering company, and its counsel, have to the CBP, local authorities, or the DOJ? The crime/fraud exception to the attorney-client privilege must be addressed by counsel with reference to both state specific and ABA Model Rules 1.6(b)(1), 1.13(c), and 1.16(b)(4) and 2. Such an analysis is especially significant in the context of a merger or acquisition when the buying company uncovers wrongdoing in advance of, or subsequent to, an acquisition and wishes to secure DOJ cooperation credit for successor liability after the transaction.

In 2003, TVPRA was expanded to allow civil causes of action for money damages against traffickers in federal courts and, since 2008, against anyone involved in the list of trafficking-related offenses “whomsoever knowingly benefits, financially or be receiving anything of value from participation in a venture which that person knew or should have known has engaged in an action in violation . . .” of Chapter 77 of Title 18. See William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008, Pub. L. No. 110-457,122 Stat. 5067, tit. ll, § 221(2) (2008), as amended by Justice for Victims of Trafficking Act of 2015, Pub. L. No. 114-22, 129 Stat. 247, tit. l, § 120(2015). TVPRA permits both compensatory and punitive damages as well as attorney’s fees. Plaintiffs frequently file other claims alongside TVPRA, including claims under the Fair Labor Standards Act, state wage and hour laws, common law theories of intentional infliction of emotional distress, false imprisonment, conversion, and breach of contract, according to the Human Trafficking Legal Center’s study Federal Human Trafficking Civil Litigation; 15 Years of the Private Right of Action. Although many settlement amounts are undisclosed, known settlement and damage awards since 2003 total in excess of $108,657,000, according to the same study. In the meantime, every state has passed laws targeting trafficking activities to varying degrees. Delaware, New Jersey, and Washington have laws fulfilling all 10 categories of laws that Polaris, a nonprofit organization dedicated to the global fight to eradicate modern slavery, determined are critical to a basic legal framework that combats human trafficking, punishes traffickers, and supports survivors.

The risk of criminal or civil litigation under applicable international, federal, or state law against a company that knowing produces, or allows affiliates to produce, goods that are the product of modern slavery (or other human rights abuses) is very real and mounting. Addressing the possibility of such a taint at any point in supply chains with the highest degree of corporate leadership, persistence, and transparency is both virtuous and strategic.