“Humans will go to the outer solar system not merely to work, but to live, to love, to build, and to stay. But the irony of the life of pioneers is that if they are successful, they conquer the frontier that is their only true home, and a frontier conquered is a frontier destroyed.”[1]

The Outer Space Treaty (“OST”),[2] ratified in 1967, is the foundation of all international space regulation. The OST establishes space as the “province of all mankind,”[3] and promotes the peaceful use and exploration of space for the “benefit and in the interests of all mankind.”[4] The Treaty requires that the parties to the OST “bear international responsibility for national activities in outer space … whether such activities are carried on by governmental agencies or by non-governmental entities,”[5] and requires that each party be “internationally liable” for damages caused by an object launched into outer space.[6] The OST prohibits claims of “national appropriation” of both outer space and celestial bodies “by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by other means.”[7] This prohibition, however, has not been deemed applicable to resources extracted from celestial bodies.[8] In 2015, responding to a rising chorus of demand from the private space industry, Congress passed the U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act (“Space Act”),[9] which “facilitate[s] commercial exploration for and commercial recovery of space resources by [U.S.] citizens.”[10] It notes that a U.S. citizen “engaged in commercial recovery of [a] space resource … shall be entitled … to possess, own, transport and sell [that resource] in accordance with applicable law.”[11] The Space Act exempts companies from regulatory oversight until 2023, which raises critical legal and regulatory questions.

As the Space Act recognizes,[12] there are open questions as to who should exercise authorization and supervision over emerging commercial space activities, and what authority are required for such activities.[13] Within this regulatory void, commercial exploration of space continues to evolve, including companies hoping to bring space resources out of orbit and back to Earth.[14] Billionaire entrepreneurs and prominent companies, such as Google,[15] invest in these companies, many of whom are willing to risk substantial capital now for promising returns in 20 to 50 years.[16] Indeed, as renowned astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson[17] argues, “[t]he first trillionaire there will ever be is the person who exploits the natural resources on asteroids.”[18]

Given the hazardous, high-risk, high-reward dynamic of space-mining ventures,[19] the privatization of title offered by the Space Act likely operates to ensure that owners internalize small and medium-scale externalities,[20] though will likely fail to ensure that owners internalize large-scale externalities,[21] such as the field of “orbital debris”[22] currently encircling the Earth,[23] which is primarily due to the profit-maximizing and “perfect externalizing machine”[24] nature of the modern multinational corporation.[25] The private space industry and the prospect of space-mining is creating very real and tangible legal struggles for the U.S. and the international community, as it is concerning to legal experts that these corporate entities will be paving the way and making up many of the rules as they go along.[26] The exciting prognostications of cosmic entrepreneurialism notwithstanding, this piece will argue that outer space should be proactively defended from the laissez-faire approach that often characterized exploration and colonization here on Earth.[27]

The purpose of this article is to demonstrate fatal flaws in how the U.S. regulates its nascent commercial space industry by examining how Federal Communications Commission (“FCC”) regulations enable the creation of orbital debris in a manner that may violate the OST, and recommend legislative language that will ensure these regulations are in compliance with the OST. This article proceeds in four parts: Part I describes the problems that orbital debris presents to all space activities.[28] Part II details how FCC regulation of satellite mega-constellation projects,[29] now unfurling around the Earth like an exoskeleton[30] in Low Earth Orbit (“LEO”),[31] likely increases the creation of orbital debris. Part III details how this FCC regulatory regime arguably violates the OST. Part IV recommends language to amend Title 51 of United States Code, which governs national and commercial space programs, with two provisions that: (1) declares outer space, including LEO orbits, to be a global commons, which could trigger the applicability of the National Environmental Policy Act (“NEPA”) to the treatment of orbital debris in LEO orbits;[32] and (2) establishes the creation of an orbital use fee (“OUF”), which will then fund orbital debris clearing projects and research related to orbital debris removal. These amendments help operationalize the OST’s language that space faring activities be for the “benefit and in the interests of all mankind”[33] by requiring that space-faring companies internalize their orbital debris-creating externalities.

I. Earth’s Orbital Tragedy of the Commons

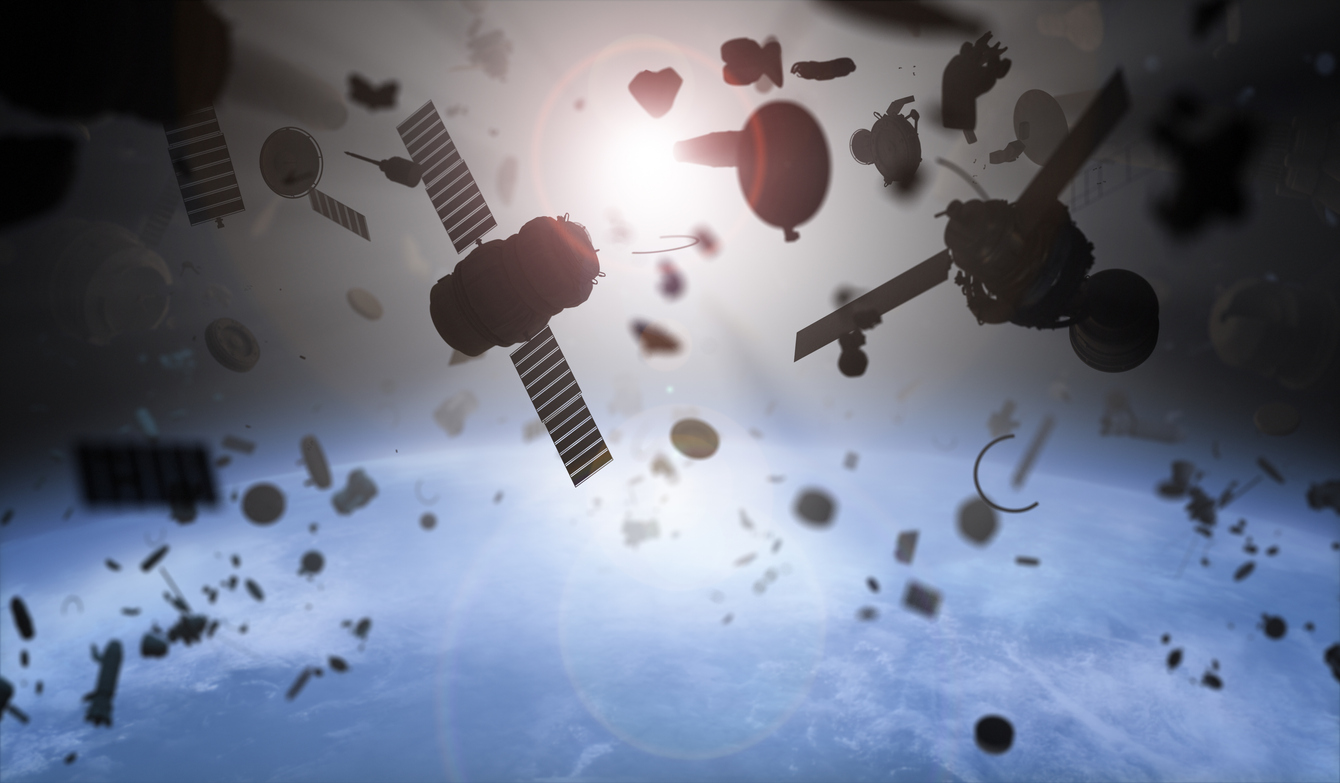

Currently, long-dead satellites, spent rocket stages, and other debris from outdated spacecraft remain in Earth orbits, and have been endangering space activities for decades.[34] NASA estimates that there are approximately 27,000 pieces of orbital debris larger than a softball,[35] 500,000 marble-sized pieces of debris, and more than 100 million pieces one millimeter or smaller, orbiting at speeds of up to 17,500 mph.[36] At these speeds, even tiny flecks of paint can damage spacecraft.[37] Much more debris that is too small to track, though large enough to imperil both human spaceflight and robotic missions, also remains in Earth orbits.[38] This untracked debris can lead to potentially dangerous orbital collisions on a regular basis, which is due to the self-generating nature of orbital debris once the amount of debris in orbit reaches a critical mass.[39] Succinctly explaining this phenomena in the New Yorker Magazine, Raffi Khatchadourian writes that:

[e]ven a minuscule shard could smash a satellite to pieces, dispersing more high-velocity debris. If the population of objects became dense enough, collisions would trigger one another in an unstoppable cascade. The fragments would grow smaller, more numerous, more uniform in direction, resembling a maelstrom of sand—a nightmare scenario that became known as the Kessler syndrome. At some point, the process would render all of near-Earth space unusable. Theoretically, Kessler mused, our planet could acquire a ring akin to Saturn’s, but made of garbage.[40]

Simulations of the evolution of orbital debris suggest that LEO is currently in the protracted initial stages of the Kessler syndrome.[41]

Into this debris field, companies are launching satellites at an exponential rate to build mega-constellations of communications satellites.[42] In just two years, the number of active and defunct satellites in LEO has increased by over 50% to roughly 5,000 as of March 30, 2021.[43] SpaceX alone launched 1,740 satellites in construction of its Starlink mega-constellation since 2019,[44] received authorization to launch an additional 30,000 Starlink satellites by the FCC in 2021,[45] now accounts for over half of close encounters between two spacecraft,[46] and is projected to be involved in 90% of all close approaches. Quoting Professor Lewis’s description of the likely scenario of cascading orbital debris created by SpaceX’s Starlink mega-constellation, Pultarova writes that:

[i]n a situation when [satellite operators] are receiving alerts on a daily basis, you can’t maneuver for everything … . The maneuvers use propellant, the satellite cannot provide service. So there must be some threshold. But that means you are accepting a certain amount of risk. The problem is that at some point, you are likely to make a wrong decision.[47]

Other multinational corporations have similar mega-constellation plans, including Amazon,[48] OneWeb,[49] and Telesat.[50]

II. FCC Regulation of Satellite Mega-constellations Incentivizes the Creation of Orbital Debris

The international legal regime governing space activities was created at a time when those activities were almost exclusively conducted by government actors.[51] Consequently, the domestic laws implementing these international legal obligations reflect the fact that space was largely the domain of government.[52] With corporate actors increasingly becoming involved in space activities,[53] domestic laws must ensure that corporate space activities are properly authorized and regulated, both for domestic policy purposes and ensuring that such activities comply with international legal obligations.[54] While the domestic legal regime is well-developed regarding established corporate activities (such as the early regulation of telephone and television satellite communications[55]), the current proliferation of satellite mega-constellations[56] exposes a void in this legal regime.[57]

Regarding the allocation of geostationary orbits (“GEO”),[58] FCC regulations implement U.S. obligations as a member of the International Telecommunications Union (“ITU”). The ITU is the United Nations treaty organization responsible for international telecommunications, including the allocation of global radio spectrum and satellite orbits.[59] These coordination activities are underpinned by the ITU’s constitution, which reminds States “that radio frequencies and any associated orbits … are limited natural resources and that they must be used rationally, efficiently and economically … so that countries … may have equitable access to those orbits,”[60] indicating a commons-based approach to governing GEO. However, no corresponding international rules exist for allocating LEO orbits, giving rise to the FCC’s current practice of assigning orbital shells to mega-constellations on a first-come, first-served basis.[61]

Given the exoskeleton-like nature of mega-constellations unfurling around the Earth,[62] and the orbital debris likely to result from their deployment,[63] any further addition of satellites to these orbital shells could become prohibitively dangerous.[64] Such a de facto occupation of orbital shells is arguably in violation of the OST’s language that space be the “province of all mankind,”[65] and there be no “national appropriation” of outer space “by means of use or occupation, or by other means.” [66] Moreover, the FCC assigns LEO orbits without either formally assessing the effects on the use of LEO orbits by other countries[67] or the likely orbital debris-related environmental impacts to LEO orbits resulting from satellite mega-constellations.[68] Under this legal regime, there is neither recognition by the FCC that LEO orbits are a finite resource[69] nor that space and Earth environments are indeed connected.[70] In this regulatory void, multiple tragedies of the commons are likely to occur,[71] particularly tragedies caused by orbital debris.[72]

III. How FCC Regulatory Practices Arguably Violate the OST

As noted earlier, the OST is the foundation of all international space regulation.[73] Furthermore, the Liability Convention was adopted to clarify the intent of Article VII of the OST.[74] While the Liability Convention does not specifically address orbital debris, as the problem was considered “relatively exotic” at the time of its adoption, it arguably creates a remedial mechanism for orbital debris damage.[75] However, a State is only liable for damage to another State’s space objects if “the damage is due to [the State’s] fault or the fault of persons for whom [the State] is responsible.”[76] Moreover, it is difficult to demonstrate fault with regard to the space environment, as collecting and producing physical evidence is impossible in most instances.[77] As such, neither the OST nor Liability Convention compellingly disincentivize debris creation in orbit.

The Space Act, which exempts companies from regulatory oversight until 2023,[78] leaves in place the FCC’s current practice of assigning orbital shells to mega-constellations on a first-come, first-served basis,[79] which is problematic for three reasons. First, due to the exoskeleton-like nature of mega-constellations unfurling around the Earth,[80] and the orbital debris likely to result from their deployment,[81] though FCC regulators are not claiming sovereignty over these orbital shells, allowing national companies to saturate them with satellites could constitute appropriation of outer space by “other means,” which is arguably in violation of Articles I, II, and IX of the OST.[82] Second, unlike the FCC’s allocation of GEO orbits, which is limited by the ITU’s constitutional principle that “any associated orbits … are limited natural resources and that they must be used rationally, efficiently and economical,”[83] no similar commons-based principle limits the FCC’s allocation of LEO orbits.[84] This practice is arguably in violation of NEPA,[85] which “requires federal agencies to take a hard look at the environmental consequences of their projects before taking action.”[86] Third, while the FCC’s 2020 “Mitigation of Orbital Debris in the New Space Age” guidelines[87] may appear to substantively address the cascading problems caused by orbital debris,[88] they only require disclosure of whether mitigation plans exist, not any statement or analysis of whether the plans are effective.[89] Responding to the National Science Foundation and Department of Energy’s request to assess the possible growth and impact of future mega-constellations on orbital debris under the FCC’s enforcement regime, a recent JASON Report found that the FCC’s guidelines:

… fall well short of what the FCC evidently thinks are required for safe traffic management in space, the new constraints on applicants are minimal … are not retroactive for existing licenses … so an applicant could meet these new FCC regulations and still suffer the catastrophic [debris creation] seen in our rate equations.[90]

The toothlessness of these guidelines underwrite the economic incentive for satellite companies to continue viewing their orbital debris as externalities incidental to the costs of doing business.[91]

By way of illustration, the worst known space collision in history occurred when the U.S. telecommunication satellite, Iridium 33, and Russia’s defunct military satellite, Kosmos-2251, collided and spawned over 1,000 pieces of orbital debris larger than 4 inches.[92] Many of these fragments were then involved in further orbital incidents.[93] Of the 95 Iridium satellites launched, 30 malfunctioned and remain stuck in LEO.[94] When Iridium CEO Matt Desch was asked if Iridium would be willing to fund the removal of their debris, he said that it would, “for a low enough cost.”[95] Desch somewhat jokingly floated the idea of paying $10,000[96] per deorbit while acknowledging, “[I] expect the cost is really in the millions or tens of millions, at which price I know it doesn’t make sense,” and argued that there is no financial incentive for removing his company’s orbital debris, explaining that “[i]ncremental ops cost saved is zero. Decreased risk to my network equals zero (all are well below). Decreased regulatory risk is zero (I spend the $$, and someone else runs into something). Removing 1 or 2 things from a catalog of 100,000 is perhaps worth only PR value.”[97]

Professor Hugh Lewis, Head of the Aeronautics Research Group at the University of Southampton, and Europe’s leading expert on space debris, highlights the consequences of such an inadequate orbital debris mitigation regime, arguing that:

[w]e place trust in a single company to do the right thing … [and] are in a situation where most of the maneuvers we see will involve Starlink. [T]hey are the world’s biggest satellite operator, but they have only been doing that for two years so there is a certain amount of inexperience … SpaceX relies on an autonomous collision avoidance system to keep its fleet away from other spacecraft. That, however, could sometimes introduce further problems. The automatic orbital adjustments change the forecasted trajectory and, therefore, make collision predictions more complicated. Starlink doesn’t publicize all the maneuvers that they’re making … [which] causes problems for everybody else because no one knows where the satellite is going to be and what it is going to do in the next few days.[98]

Further echoing the problems of placing singular trust in SpaceX, for example, to do the right thing in this new space age, its terms of service for beta users of its Starlink mega-constellation broadband service are revealing in this regard, as one clause provides that:

[f]or services provided on Mars, or in transit to Mars via Starship or other colonization spacecraft, the parties recognize Mars as a free planet and that no Earth-based government has authority or sovereignty over Martian activities. Accordingly, Disputes will be settled through self-governing principles, established in good faith at the time of the Martian settlement.[99]

As failing to recognize the applicability of the OST to the planet Mars is arguably in violation of the OST,[100] any general expectation that the company now responsible for over half of near collisions in LEO[101] would do the right thing is unrealistic. Accordingly, the FCC’s laissez-faire enforcement regime is in substantive need of reform in a manner that ensures compliance with the OST’s language of prohibiting claims of “national appropriation” of outer space “by other means” and promoting the peaceful use and exploration of space for the “benefit and in the interests of all mankind.”[102]

IV. Suggested Amendments to Title 51 of the United States Code

A. Recommendation One: Amend Title 51 of United States Code to Ensure that Outer Space is Regulated as a Global Commons, which Triggers the Applicability of NEPA to the Governance of LEO Orbits Under the OST

NEPA “requires federal agencies to take a hard look at the environmental consequences of their projects before taking action.”[103] Notably, this “hard look” extends beyond an agency’s individual actions to any actions by third parties that the agency authorizes.[104] Moreover, if federal actions have a significant impact on the global commons, which are defined as areas in which no nation maintains exclusive jurisdiction, but in which every nation has a stake,[105] NEPA applicability is similarly triggered.[106] In such instances, NEPA requires the completion of an Environmental Assessment,[107] an Environmental Impact Statement,[108] or the classification of the action as categorically excluded from environmental review.[109] Accordingly, Courts have applied NEPA’s requirements when federal actions occur in the global commons.[110]

Regarding whether outer space should be considered a global commons in the context of mitigating orbital debris, Professor Robert C. Bird argues that:

[a]t its core, regulation of space debris is an environmental problem of international proportions. Emission of space debris is more likely to negatively affect the community of nations as a whole, rather than an individual state. Outer space is a classic example of a global commons, similar to the open seas. When a nation discharges space debris, it reduces the utility of the space commons for all states.[111]

Indeed, just as the FCC finding[112] that satellite mega-constellations are categorically excluded from NEPA review is legally dubious,[113] the FCC’s similar disregard of viewing outer space as a global commons by merely doubting whether “alleged impacts in space are even within the scope of NEPA,”[114] is similarly unavailing. Accordingly, the FCC’s findings need further clarification, and its seemingly laissez-faire enforcement regime is in substantive need of reform.

In support of the OST’s language establishing space as the “province of all mankind,”[115] promoting its peaceful use and exploration for the “benefit and in the interests of all mankind,”[116] prohibiting claims of “national appropriation” of both outer space and celestial bodies “by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by other means,”[117] and requiring that parties “bear international responsibility for national activities in outer space … whether such activities are carried on by governmental agencies or by non-governmental entities,”[118] this article’s proposed amendment to Title 51 of United States Code would read:

Title 51, of the United States Code, is amended by adding at the end the following:

Subtitle VIII – Authorization and Supervision of Nongovernmental Space Activities

CHAPTER 801—CERTIFICATION TO OPERATE SPACE OBJECTS

§ 801**. Global commons

Notwithstanding any other provision of law, outer space shall be considered a global commons.

§ 801**. Certification authority, application, and requirements

(A) The Federal Government shall presume all obligations of the United States under the Outer Space Treaty are obligations to be imputed upon United States nongovernmental entities.

(B) The Federal Government shall interpret and fulfill its international obligations under the Outer Space Treaty in a manner that ensures nongovernmental entities are in conformity with the Outer Space Treaty.

B. Recommendation Two: Amend Title 51 of United States Code to Establish an Orbital Use Fee that will Fund Orbital Debris Clearing Projects and Research Related to Orbital Debris Removal

A number of technological and regulatory solutions, such as active debris removal[119] and voluntary orbital debris mitigation guidelines,[120] are currently being explored by regulatory authorities.[121] While these efforts are important in ensuring the sustainable use of LEO orbits, they do not address the underlying incentive problem for satellite operators. Namely, they are incentivized to view both their orbital debris and the costs that it imposes on others as externalities.[122] As such, without the internalization of these externalities, efforts to fully address the orbital debris problem will likely be ineffective.[123] Notably, a National Academy of Sciences study found that orbital debris removal may worsen the economic damages from congestion by increasing incentives to launch.[124] As satellite operators are prohibited from securing exclusive property rights to orbital shells under the OST,[125] and are unlikely to recover economic damages resulting from orbital debris collisions under the Liability Convention,[126] prospective operators “face a choice between launching profitable satellites, thereby imposing current and future collision risk on others, or not launching and leaving those profits to competitors.”[127] This dynamic represents a classic tragedy of the commons problem.[128] However, under Article VI of the OST,[129] this problem can be partially solved through an OUF[130] levied by the FCC. The monies received from this fee would then be used to fund private orbital debris clearing projects[131] and research related to orbital debris removal.

Though such an OUF may be seen as an unreasonable growth restraint on the nascent space industry,[132] a Pew study found that in the case of nearly a dozen industries, the costs of implementing new regulations were less than estimated while the economic benefits were greater than estimated.[133] Moreover, these regulations did not significantly impede the economic competitiveness of the industry.[134] An OUF consistent with what this article proposes would even the playing field for commercial-satellite operators in a manner consistent with OST principles[135] and, as OneWeb’s founder argued, while “thoughtful, common-sense rules” likely increase operating costs for commercial-satellite operators, they protect the environment and ensure that the U.S. commercial satellite industry continues to grow.[136] While the U.S. cannot address the issue of reducing orbital debris on its own, it can make a substantial contribution through demonstrating responsible orbital debris mitigation measures, such as those advocated in this article.

In support of the aforementioned OST language,[137] this article’s second proposed amendment to Title 51 of United States Code would read:

Title 51, of the United States Code, is further amended by adding at the end the following:

CHAPTER 802—ADMINISTRATIVE PROVISIONS RELATED TO CERTIFICATION AND PERMITTING

§ 802XX. Orbital use fee purpose

The Administrator, in conjunction with the heads of other Federal agencies, shall take steps to fund orbital debris removal projects, technologies, and research that will enable the Administration to decrease the risks associated with orbital debris.

§ 802XX. Administrative authority

In order to carry out the responsibilities specified in this subtitle, the Secretary may impose an orbital use fee for the placement of objects in low Earth orbits on a nongovernmental entity holder of, or applicant for:

(1) a certification under chapter 801; or

(2) a permit under chapter 802.

V. Conclusion

The OST establishes space as the “province of all mankind”[138] and promotes its peaceful use and exploration for the “benefit and in the interests of all mankind.”[139] The OST further requires that “Parties to the Treaty … bear international responsibility for national activities in outer space … whether such activities are carried on by governmental agencies or by non-governmental entities,”[140] and requires that each “Party to the treaty … [be] internationally liable” for damages caused by an object launched into outer space.[141] Finally, the OST prohibits claims of “national appropriation” of both outer space and celestial bodies “by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by other means.”[142] The Space Act “facilitate[s] commercial exploration for and commercial recovery of space resources by [U.S.] citizens … ”[143] and exempts companies from regulatory oversight until 2023.[144] However, the FCC’s laissez-faire enforcement of satellite mega-constellation projects is arguably in violation of the OST[145] due to the saturation of these mega-constellations in LEO and their likely resulting orbital debris.[146]

While the exploitation and use of space resources, as conceived under the Space Act, is likely two or three decades away,[147] proactive legislation is critical for ensuring that regulations are in place to address problems that will inevitably arise, such as the debris created by harvesting asteroids in near Earth orbits.[148] Indeed, the existing legal regime is unresponsive to both current and future problems arising from the orbital debris expanding like planetary rings of garbage around our homeworld.[149] Consistent with the language of the OST,[150] this article’s recommendations will help ensure that outer space not become an orbital debris strewn battle-ground for the national and corporate appropriation of orbital and celestial resources, but rather, the “province of all mankind.”[151]

* The author would like to thank Adam M. Burton, Jeremy A. Schiffer, and the editors of Business Law Today for their helpful comments and suggestions.

[1] See, Robert Zubrin., On the Way to Starflight: The Economics of Interstellar Breakout, in Starship Century: Toward the Grandest Horizon 101 (Microwave Sciences, 2013) (detailing several scientific, economic, and anthropological perspectives on the challenges and requirements for humans to become a sustainable interstellar species).

[2] See The Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, Jan. 27, 1967, 610 U.N.T.S. 205 (hereinafter the OST) (ratified in 1967, the OST was the first international space law treaty and serves as the foundation of all international space law).

[3] Id. at Art. I.

[4] Id. at Part Two, A.

[5] Id. at Art. VI.

[6] Id. at Art. VII; see also Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects art. 2, Mar. 29, 1972, 24 U.S.T. 2389, 961 U.N.T.S. 187 [hereinafter Liability Convention], which was adopted to clarify the intent of Art. VII of the OST. See Meghan R. Plantz, Note, Orbital Debris: Out of Space, 40 Ga. J. Int’l & Comp. L. 585, 603 (2012).

[7] Id. at Art. II.

[8] See Spurring Private Aerospace Competitiveness and Entrepreneurship Act of 2015, Pub. L. No. 114-90, 129 Stat. 704 (2015) (codified as amended at 51 U.S.C. § 10101) at § 51303 (hereinafter the Space Act).

[9] Id.

[10] Id. at § 51302.

[11] Id. at § 51303.

[12] Id. at § 51302.

[13] Under Article VI of the OST:

[p]arties to the Treaty shall bear international responsibility for national activities in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, whether such activities are carried on by governmental agencies or by non-governmental entities, and for assuring that national activities are carried out in conformity with the provisions set forth in the present Treaty.

The OST further provides that: “[t]he activities of non-governmental entities in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, shall require authorization and continuing supervision by the appropriate State Party to the Treaty.” See supra note 2 at Art. VI.

[14] See generally, Michael Jensen, Asteroidae Naturae: What it Takes to Capture an Asteroid, 45 Sw. L. Rev. 757, (2016) (noting that while space mining is in its beginning stages, companies are announcing plans for prospecting near Earth asteroids); Tomas R. Irwin, Space Rocks: A Proposal to Govern the Development of Outer Space and its Resources, 76 Ohio St. L.J. 217 (2015) (noting that, increasingly, private companies are becoming involved in space exploration, including plans for resource extraction and utilization); Craig Foster, Excuse me, You’re Mining my Asteroid: Space Property Rights and the U.S. Space Resource and Utilization Act of 2015, 2016 U. Ill. J.L. Tech & Pol’y 407 (2016) (describing the current technological era as a merging of science fiction into science fact, Foster details a number of companies and their plans for space mining); Matthew Schaefer, The Need for Federal Preemption and International Negotiations Regarding Liability Caps and Waivers of Liability in the U.S. Commercial Space Industry, 33 Berkeley J. Int’l L. 223 (2015) (noting that the maturing commercial space industry is critical to both U.S. economic interests and national security); Andrew Lintner, Extraterrestrial Extraction: International Implications of the Space Resource Exploration and Utilization Act of 2015, 40 SUM Fletcher F. World Aff. 139 (2016) (arguing that the emergence of private companies and their desire to commercialize the cosmos are becoming more feasible and profitable); Major Susan J. Trepczynski, New Space Activities Expose a Potential Regulatory Vacuum, 40 No. 3 The Reporter 12 (2016) (arguing that since private companies are becoming increasingly involved in, and vital to, space activities, domestic law must evolve to ensure that such activities are compliant with U.S. obligations under the OST); Caroline Arbaugh, Gravitating Toward Sensible Resolution: the PCA Optional Rules for the Arbitration of Disputes Relating to Outer Space Activity, 42 Ga. J. Int’l & Comp. L. 825 (2014) (noting that a number of private companies have plans, and the potential technology in the near future, to mine celestial bodies for precious metals).

[15] Goldman Sachs Equity Research Report, Space: The Next Investment Frontier (April 4, 2017), http://www.fullertreacymoney.com/system/data/files/PDFs/2017/October/4th/space%20-%20the%20next%20investment%20frontier%20-%20gs.pdf at 55 (noting that “a lot of investment has been from or into well-known players in the sector—like Google and Fidelity Investing in SpaceX or SoftBank investing in OneWeb. But there have been dozens of small investment firms putting money into smaller privates, as well”).

[16] See, e.g., Space: Investing in the Final Frontier, Morgan Stanley (July 24, 2020), https://www.morganstanley.com/ideas/investing-in-space (estimating that the global space industry could generate revenue of more than $1 trillion or more in 2040, up from the current $350 billion); Capital Flows as Space Opens for Business, Morgan Stanley (July 21, 2020), https://www.morganstanley.com/ideas/future-space-economy (describing the nascent space economy as demonstrable fertile grounds for private investment). The article notes that this new “space race is being powered not just by government but by a new crop of startups and visionaries. …entrepreneurs, strategic partnerships, and venture capital have been leading the charge on funding” for these ventures and that, for some of these investments, “the exit plans can be 50 years out.” The article further discusses that “[we’re] seeing a tremendous amount of interest in this area from angel investors, venture capital and private-equity firms…” and that much of this is real passion in the industry, though “some of it is simply fear of being late to the party. Things are changing at such a rapid pace that investors are saying they have to keep up with the times… [and] [b]ecause success in space promises to be a multidecade endeavor—with returns on some lofty endeavors that could be many years away—this new economy requires patient investors. One sign of investors’ willingness to wait is the increasing reliance on permanent and long-term capital funds.” Id; European Space Agency, ESA Space Resources Strategy (May 23, 2019), https://sci.esa.int/documents/34161/35992/1567260390250-ESA_Space_Resources_Strategy.pdf (concluding that 88 billion to 206 billion dollars over the 2018–2045 period are expected from space resource utilization). Id. at 5. The report further argues that:

The resources of space offer a means to enable sustainable exploration of the Moon and Solar System… [and the] utilisation of space resources for exploration may be within reach for the first time; made possible by recent advances in our knowledge and understanding of the Moon and asteroids, increased international and private sector engagement in space activities and the emergence of new technologies.

Id. at 2; Luxembourg Space Agency, Opportunities for Space Resources Utilization: Future Markets & Value Chains (Dec. 2018), https://space-agency.public.lu/dam-assets/publications/2018/Study-Summary-of-the-Space-Resources-Value-Chain-Study.pdf (noting that the nascent space resources utilization industry is expected to generate a market revenue of 88 billion to 206 billion dollars over the 2018–2045 period, supporting a total of 845,000 to 1.8 million full time employees). Id. at 9. The report further notes that the “[i]ncorporation of space resources into exploration missions will reduce costs and improve their economic viability” and that, as such, “[s]pace resources will play a foundational role in the future of in-space economies.” Furthermore, the report argues that:

[t]he exploitation of volatiles – mainly water – and other resources such as raw regolith or metals available on celestial bodies requires the establishment of new supply chains for effective utilization. Although the time horizon for the first operational applications is expected to be in the next decade, preparatory steps are being taken today in developing the enabling technologies and obtaining prospecting information on future exploitable space resources. It is in the interest of pioneering space companies, space agencies, and other visionary organizations to ensure they capture early opportunities and anticipate future needs for the space resources utilization.

Id. at 3; See supra note 15 at 4 (noting that “[w]hile relatively small markets today, rapidly falling costs are lowering the barrier to participate in the space economy, making new industries like space tourism, asteroid mining, and on-orbit manufacturing viable.”).

[17] Neil deGrasse Tyson is the fifth head of the world-renowned Hayden Planetarium, in operation since 1935, recipient of NASA’s Distinguished Public Service Medal and the U.S. National Academy of Sciences Public Welfare Medal, a research associate of the Department of Astrophysics at the American Museum of Natural History, and is a television host. Neil deGrasse Tyson, https://www.haydenplanetarium.org/tyson/index.php (last visited June 7, 2021).

[18] See Katie Kramer, Neil deGrasse Tyson Says Space Ventures Will Spawn First Trillionaire, NBC News (May 3, 2015), https://www.nbcnews.com/science/space/neil-degrasse-tyson-says-space-ventures-will-spawn-first-trillionaire-n352271 (providing a favorable comparison with the exploits of Christopher Columbus in the Americas, Tyson argues that such commercial activity is vital to both the pursuit of space sciences and the national interest).

[19] See supra note 14 and accompanying text; see supra note 16 and accompanying text.

[20] For an influential account, see generally, Robert C. Ellickson, Property in Land, 103 Yale L. J. 1315 (1993); Jared B. Taylor, Note, Tragedy of the Space Commons: A Market Mechanism Solution to the Space Debris Problem, 50 Colum. J. Transnat’l L. 254 (2011).

[21] Id. at 1334.

[22] See, e.g., United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs: Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines of the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, http://www.unoosa.org/pdf/publications/st_space_49E.pdf (last visited June 3, 2021) (Defining “space debris” as “all man-made objects, including fragments and elements thereof, in Earth orbit or re-entering the atmosphere, that are non-functional”); Astromaterials Research & Exploration Science Orbital Debris Program Office, https://www.orbitaldebris.jsc.nasa.gov/faq/# (last visited May 31, 2021) (Defining “orbital debris” as “any human-made object in orbit about the Earth that no longer serves any useful purpose”); see also David Tan, Towards a New Regime for the Protection of Outer Space as the “Province of All Mankind,” 25 Yale J. Int’l L. 145, 151 n.21 (2000) (noting space debris can be defined as “[a]ny man-made earth-orbiting object which is non-functional with no reasonable expectation of assuming or resuming its intended function or any other function for which it is or can be expected to be authorized”); see also Jennifer M. Seymour, Note, Containing the Cosmic Crisis: A Proposal for Curbing the Perils of Space Debris, 10 Yale J. Geo. Int’L Envtl L. Rev 891, 895 (1998) (“There is no internationally accepted definition of the term ‘space debris.’ However, the term’s popular meaning is any non-functional human-made object or objects in outer space”).

[23] See generally, Joseph Kurt, Triumph of the Space Commons: Addressing the Impending Space Debris Crisis Without an International Treaty, 40 Wm. & Mary Envtl. L. & Pol’y Rev. 305, 307 (2015); Chelsea Muñoz-Patchen, Regulating the Space Commons: Treating Space Debris as Abandoned Property in Violation of The Outer Space Treaty, 19 Chi. J. Int’l L. 233 (2018); Robert C. Bird, Procedural Challenges to Environmental Regulation of Space Debris, 40 Am. Bus. L.J. 635, 664 (2003); Plantz, supra note 6 at 592; Gabrielle Hollingsworth, Comment, Space Junk: Why the United Nations Must Step in to Save Access to Space, 53 Santa Clara L. Rev. 239, 264 (2013); Scott J. Shackelford, Governing the Final Frontier: A Polycentric Approach to Managing Space Weaponization and Debris, 51 Am. Bus. L.J. 429, 430 (2014); Michael W. Taylor, Trashing the Solar System One Planet at a Time: Earth’s Orbital Debris Problem, 20 Geo. Int’l Envtl. L. Rev. 1, 56-57 (2007); Natalie Pusey, The Case for Preserving Nothing: The Need for a Global Response to the Space Debris Problem, 21 Colo. J. Int’l Envtl. L. & Pol’y 425, 426 (2010); Taylor, supra note 2; Sophie Kaineg, The Growing Problem of Space Debris, 26 Hasting Envtl. L.J. 277 (2020); Michael W. Taylor, Trashing the Solar System One Planet at a Time: Earth’s Orbital Debris Problem, 20 Geo. Int’l Envtl L. Rev. 1, 25-26 (2007).

[24] See, e.g., Lawrence E. Mitchell, Corporate Irresponsibility: America’s Newest Export, 276-78 (2001) (noting that since American companies are legally incentivized to focus on the short-term wealth maximization of their shareholders, and that a defining feature of these companies are their limited liability, such companies are necessarily incentivized to become externalizing machines). Indeed, Mitchell argues that the “corporation is an externalizing machine, in the same way that a shark is a killing machine… [it] is deliberately programmed, indeed legally compelled, to externalize costs without regard for the harm it may cause to people, communities and the natural environment.” Id. at 49-53.

[25] See, e.g., Harold Demsetz, 57 America’s Am. Econ. Rev. 347-50 (1967) (providing a foundational conception of property rights, Demsetz famously observed that property rights in a resource tend to emerge to help “internalize externalities when the gains of internalization become larger than the cost of internalization”). An externality arises when “the activity of one entity … directly affects the welfare of another in a way that is not transmitted by market prices.” America’s Am. Econ. Harvey S. Rosen, Public Finance 86 (5th ed. 1999). Indeed, this productivity impulse is reflected, for example, in the doctrine of first possession; see also Mario Rizzo, Law Amid Flux: The Economics of Negligence and Strict Liability in Tort, 9 Am. Econ J. Legal Stud. 291, 298 (1980) (describing a major purpose of tort law as a means of internalizing the cost of external harms, thereby incentivizing actors to find ways to reduce their cost by decreasing external harms); see also Joel Bakan, The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profits and Power, 1-2 (2004) (Discussing the behavioral characteristics of the corporate form, the author notes that the “corporation’s legally defined mandate is to pursue, relentlessly and without exception, its own self-interest, regardless of the often-harmful consequences it might cause to others”). As such, that millions of pieces of unattributed space junk currently orbit Earth should surprise no one.

[26] See generally Thomas E. Simmons, Deploying the Common Law to Quasi-Marxist Property on Mars, 51 Gonz. L. Rev. 25 (2016); Robbie Gramer, Striking Gold in Space, Washington Lawyer, (2016); Arbaugh, supra note 14; see also Kara Swisher, Why Are Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos So Interested in Space?, February 26, 2021, NYTimes, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/26/opinion/mars-nasa-musk.html. Noting the considerable influence of Elon Musk’s SpaceX and Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin in Earth’s nascent commercial space industry and much of the fawning media coverage of their exploits, Swisher argues that:

[w]e have handed over so much of our fate to so few people over the last decades, especially when it comes to critical technology. As we take tentative steps toward leaving Earth, it feels like we are continuing to place too much of our trust in the hands of tech titans. Think about it: We the people invented the internet, and the tech moguls pretty much own it. And we the people invented space travel, and it now looks as if the moguls could own that, too. Let’s hope not. NASA, and other government space agencies around the world, need our continued support to increase space exploration.

Id.

[27] Matthew Feinman, Mining the Final Frontier: Keeping Earth’s Asteroid Mining Ventures from Becoming the Next Gold Rush, 14 Pitt. J. Tech. L. & Pol’y 202 (2014) (noting the excitement in the nascent space industry of extracting precious metals from asteroids, Feinman argues that “[b]efore these companies can begin mining, stronger property laws are needed to ensure that the Asteroid Belt of our solar system is not described as the next California Gold Rush and as having the lawlessness associated with it”); Samuel Roth, Developing a Law of Asteroids: Constants, Variables, and Alternatives, 54 Colum. J. Transnat’l L. 827, 866 (2016) (detailing the moral concerns triggered by the prospect of asteroid mining, Roth argues that “[i]In recent decades, men and women from around the globe have come to profoundly regret the choices of previous generations to consume Earth’s natural resources in ways that have left lasting scars”); see generally, Intergovernmental panel on climate change, climate change 2014 synthesis report (2015), https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/05/SYR_AR5_FINAL_full_wcover.pdf.

[28] See generally supra note 23.

[29] Mega-constellations are groups of dozens, or even hundreds, of mass-produced satellites united in a common task. This recent technological development is leading to an increasingly congested LEO environment, which increases the potential of orbital collisions between spacecraft, which then creates more orbital debris that in turn increases the likelihood of more collisions. See e.g. Aaron C. Boley & Michael Byers, Satellite Mega-Constellations Create Risks in Low Earth Orbit, the Atmosphere and on Earth. Sci. Rep. 11 10642 (2021) (arguing that the current regulatory framework is insufficient to curtail the likely multiple tragedies of the commons to the availability of Earth orbits, due to orbital debris, the Earth’s upper atmosphere, due to emissions from spacecraft, and ground-based astronomy, due to the number of satellites that can obstruct ground-based telescopes); Leonard David, Space Junk Removal Is Not Going Smoothly, Scientific American, April 14, 2021, available at https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/space-junk-removal-is-not-going-smoothly/ (arguing that the increasing satellite congestion in low Earth orbits is creating a “Space Age ‘tragedy of the commons’” fueled by increasing orbital debris); Nathaniel Scharping, The Future of Satellites Lies in the Constellations, Discover Magazine, June 30, 2021, available at https://www.discovermagazine.com/the-sciences/the-future-of-satellites-lies-in-the-constellations (noting the advent of mega-constellations as a driving force in the increasing the odds of collisions that create more orbital debris).

[30] See Marina Koren, Private Companies are Building an Exoskeleton Around Earth, The Atlantic, May 24, 2019, available at https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2019/05/spacex-satellites-starlink/590269/ (noting the development of mega-constellations by several companies, the article quotes the CEO of SpaceX, Elon Musk, regarding how its Starlink mega-constellation, the aim of which is to provide high-speed and low latency broadband internet across Earth, will unfurl. Once thousands of these satellites are in LEO, Musk notes that they will fan out across LEO “like spreading a deck of cards on the table.”) Id.

[31] LEO is defined as the region from Earth’s edge to 2,000 kilometers of altitude, or roughly 1,200 miles above Earth’s edge. See NASA, https://www.orbitaldebris.jsc.nasa.gov/photo-gallery.html; Center for Strategic and International Studies, https://aerospace.csis.org/aerospace101/popular-orbits-101/ (last visited September 6, 2021). The majority of all orbital debris is located in LEO. See NASA Office of Inspector General: NASA’s Efforts to Mitigate the Risks Posed by Orbital Debris, January 27, 2021, https://oig.nasa.gov/docs/IG-21-011.pdf at 3.

[32] NEPA “requires federal agencies to take a hard look at the environmental consequences of their projects before taking action.” 42 U.S.C. § 4321 (2018). An agency is responsible for NEPA review of its actions if it is reasonably foreseeable that those actions could lead a third party to engage in activity that could significantly impact the environment. See, e.g., Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence v. Salazar, 612 F.Supp. 2d 1, 13 (D.D.C. 2009); see, e.g., Ramon J. Ryan, The Fault in Our Stars: Challenging the FCC’s treatment of Commercial Satellites as Categorically Excluded from Review under the National Environmental Policy Act, 22 Vand. J. Ent. & Tech. L. 923, (2020) (arguing that the FCC’s current stance that commercial satellite mega-constellation projects are categorically excluded from environmental reviews may not survive judicial scrutiny, as the FCC’s stance is best understood as conclusory. Ryan contends that the FCC has opened itself up to litigation by not following the NEPA statute and assessing environmental impacts of commercial satellites, such as the orbital debris likely resulting from mega-constellations. These impacts, he argues, clearly merit an assessment under the NEPA statute, which requires the FCC to assess the environmental impacts of commercial satellite projects before approving them for launch). see also discussion infra Part IV, A.

[33] See supra note 2 at Part Two, A.

[34] See Ryan Morrison, International Space Station is Forced to Carry Out and Emergency Manoeuvre to Avoid Being Hit by a Piece of Debris From a 2018 Japanese Rocket, Daily Mail, September 22, 2020 available at https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-8761867/ISS-initiates-avoid-space-debris.html; see also Samantha Masunaga, A Satellite’s Impending Fiery Demise Shows How Important it is to Keep Space Clean, L.A. Times, June 27, 2021, available at https://www.latimes.com/business/story/2021-06-27/satellites-self-destruct-clean-up-space-junk; Adrian Moore & Rebecca Van Burken, It’s Time for US to Get Serious About Cleaning Up Space Junk, The Hill, July 27, 2021, available at https://thehill.com/opinion/technology/564945-its-time-for-us-to-get-serious-about-cleaning-up-space-junk.

[35] See Space Debris and Human Spacecraft, National Aeronautics & Space Administration, https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/news/orbital_debris.html (last visited August 12, 2021).

[36] Id.

[37] NASA reports that “a number of space shuttle windows were replaced because of damage caused by material that was analyzed and shown to be paint flecks.” Indeed, NASA further documents that “millimeter-sized orbital debris represents the highest mission-ending risk to most robotic spacecraft operating in [LEO].” Id.

[38] Id.

[39] See e.g., Boley & Byers supra note 29; see also supra note 30 and accompanying text.

[40] See Raffi Khatchadourian, The Elusive Peril of Space Junk, The New Yorker Magazine, September 28, 2020, available at https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/09/28/the-elusive-peril-of-space-junk; see also, e.g., Donald J. Kessler & Burton G. Cour-Palais, Collision Frequency of Artificial Satellites: The Creation of a Debris Belt, J. Geophys. Res. 83, 2637 (1978); see also Paul B. Larsen, Solving the Space Debris Crisis, 83 J. Air L. & Commerce 475, 476-82 (2018); Stephan Hobe, Space Law 112-14 (2019); Alexander William Salter, Space Debris: A Law and Economics Analysis of the Orbital Commons, 19 Stanford Tech. L. Rev. 221, 224-27 (2016).

[41] See Boley & Byers supra note 29 at 11; see also, e.g., NASA Office of Inspector General, supra note 31 at 14:

Multiple studies by NASA and other space agencies have found that orbital debris has already reached critical mass, and collisional cascading will eventually happen even if no more objects are launched into orbit. According to NASA, by 2005 the amount and mass of debris in LEO had grown to the point that even if no additional objects were launched into orbit, collisions would continue to occur, compounding the instability of the debris environment and increasing operational risk to spacecraft by 2055 unless measures were taken to curb the growth of the debris population. However, the amount of orbital debris has not decreased, or even stabilized, since 2006. Instead, the largest increases of new spacecraft and debris generation have occurred in LEO since 2006.

Id.

[42] See Masunaga supra note 34. Quoting Assistant Professor at Arizona State University’s School for the Future of Innovation in Society, Masunaga writes:

[t]he rate at which we’re launching is increasing exponentially and is proposed to increase five to tenfold over the coming decade… [w]e don’t want to raise [sic] alarm by saying it’s so, so terrible, but the thing is, it potentially could be so, so terrible if we don’t do anything about ensuring that people think more sustainably about how to do space activities.

Id; see also supra note 29 and accompanying text.

[43] See Boley & Byers supra note 29 at 11 (noting that the exponential development of mega-constellations “risks multiple tragedies of the commons” to all LEO orbits, the chemical makeup of Earth’s upper atmosphere, and ground-based astronomy, due to the increased likelihood of orbital collisions and other externalities associated with such satellite launches. The article further argues that “international cooperation is urgently needed, along with a regulatory system that takes into account the effects of tens of thousands of satellites”). Id.

[44] See Michael Sheetz, SpaceX Adding Capabilities to Starlink Internet Satellites, Plans to Launch Them with Starship, CNBC, August 19, 2021, available at https://www.cnbc.com/2021/08/19/spacex-starlink-satellite-internet-new-capabilities-starship-launch.html (describing an amendment to Starlink’s FCC authorization, Sheetz notes that these Gen2 Starlink satellites will be both heavier and larger than originally designed); see also supra note 30 and accompanying text regarding the purpose of the Starlink project.

[45] See In the Matter of Space Exploration Holdings, LLC, FCC 21-48 (April 23, 2021) https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-21-48A1.pdf.

[46] See see, e.g., Tereza Pultarova, SpaceX Starlink Satellites Responsible for Over Half of Close Encounters in Orbit, Scientist Says, Space.com, August 18, 2021, available at https://www.space.com/spacex-starlink-satellite-collision-alerts-on-the-rise. Quoting Professor Hugh Lewis, Head of the Aeronautics Research Group at the University of Southampton and Europe’s leading expect on space debris, Pultarova writes:

I have looked at the data going back to May 2019 when Starlink was first launched to understand the burden of these mega-constellations… . Since then, the number of encounters picked up by the Socrates database has more than doubled and now we are in a situation where Starlink accounts for half of all encounters.

Id.

[47] Id; see also discussion infra Part II.

[48] See Elizabeth Howell, Amazon’s 1st Kuiper Megaconstellation Satellites will Launch on a ULA Atlas V Rocket, Space.com, April 20, 2021, available at https://www.space.com/amazon-kuiper-megaconstellation-atlas-v-rockets.

[49] See Jonathan Amos, OneWeb Lays Path to Commercial Broadband Services, BBC News, July 1, 2021 available at https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-57674882.

[50] See Eva Mathews & Steve Scherer, Telesat Closer to Financing Satellite Network after Canada Investment, Reuters August 12, 2021, available at https://www.reuters.com/technology/telesat-get-14-billion-investment-canadian-government-2021-08-12/.

[51] See Paul Stephen Dempsey, National Laws Governing Commercial Space Activities: Legislation, Regulation, & Enforcement, 36 Nw. J. Int’l L. & Bus. 1-4 (2016); see also, e.g., NASA Office of Inspector General, supra note 31 at 14:

Ten years ago, the number of spacefaring entities was relatively small, limited mainly to government space agencies with budgets capable of supporting the development of complex technology, spacecraft, and launch vehicles. However, the advent of the commercial launch industry and miniaturized satellites have significantly decreased the costs of owning and launching spacecraft over the last 10 years, enabling more countries and even commercial entities to develop, own, and launch space-based assets. … This rapid increase of space activity has simultaneously accelerated the creation of orbital debris.

Id; see also supra note 2 and accompanying text.

[52] Id. See generally Ian Blodger, Reclassifying Geostationary Earth Orbit as Private Property: why Natural Law and Utilitarian Theories of Property Demand Privatization, 17 Minn. J. L. Sci. & Tech. 409 (2016); Foster, supra note 14; Diane Howard, Safety as a Synergistic Principle in Space Activities, 10 Fiu L. Rev. 713 (2015); Steven A. Mirmina, Astronauts Redefined: The Commercial Carriage of Humans to Space and the Changing Concepts of Astronauts Under International and U.S. Law, 10 Fiu L. Rev. 669 (2015); Ross Meyers, The Doctrine of Appropriation and Asteroid Mining: Incentivizing the Private Exploration and Development of Outer Space, 17 Or Rev. Int’l L. 183 (2015).

[53] See supra note 15 and accompanying text.

[54] See supra note 13 and accompanying text regarding the obligation of OST signatories to authorize and continuously supervise the activities of their non-governmental entities in outer space.

[55] See supra note 51 and accompanying text.

[56] See supra note 29 and accompanying text; see also supra note 30 and accompanying text.

[57] See supra note 16 and accompanying text; see supra note 26; see also generally Lintner supra note 14 (arguing that the Space Act counterintuitively creates more business uncertainty due to its questionable compatibility with U.S. obligations under the OST); see also Kevin MacWhorter, Sustainable Mining: Incentivizing Asteroid Mining in the Name of Environmentalism, 40 Wm. & Mary Envtl. L & Pol’y Rev. 645 (2016) (arguing that without an amendment to the OST that creates privity of title in the resources extracted from celestial bodies, both domestic and international law are insufficient to incentivize sustainable space industries); see generally Thomas J. Herron, Deep Space Thinking: What Elon Musk’s Idea to Nuke Mars Teaches Us About Regulating the ‘Visionaries and Daredevils’ of Outer Space, 41 Colum. J. Envtl. L. 553 (2016); Matthew Schaefer, The Need for Federal Preemption and International Negotiations Regarding Liability Caps and Waivers of Liability in the U.S. Commercial Space Industry, 33 Berkeley J. Int’l L. 223 (2015).

[58] GEO is an orbital zone above Earth’s equator where the satellite remains above the same point on Earth. GEO is important for satellite communication because it allows permanent installations on Earth to point directly to the satellite, receiving information without constant recalibration. The number of satellites that can use a GEO at a time is limited to approximately 2000 satellites due to the potential for communication frequency interference. GEO differs from LEO in that LEO objects are closer to Earth’s surface and do not remain fixed over a specific location. See Basics of Space Flight; Planetary Orbits, https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/basics/chapter5-1/ (last visited September 2, 2021); see also generally Michael J. Finch, Comment, Limited Space: Allocating the Geostationary Orbit, 7 NW. J. Int’l L. & Bus. 788, (1986).

[59] For more information on ITU regulatory publications see the ITU Radiocommunication Sector (ITU-R) webpage at: https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-R/Pages/default.aspx. The United States is bound by ITU documents and implements many of the specific technical obligations through regulations, such as those promulgated by the FCC. See generally Lawrence D. Roberts, A Lost Connection: Geostationary Satellite Networks and the International Telecommunication Union, 15 Berkeley Tech. L.J. 1095, 1106, 1111 (2000).

[60] See ITU Const. of 2018 art. 44 § 196, available at https://www.itu.int/en/council/Documents/basic-texts/Constitution-E.pdf.

[61] See, e.g., FCC Fact Sheet, Updating Rules for Non-Geostationary-Satellite Orbit Fixed-Satellite Service Constellations, Sept. 7, 2017, available at https://transition.fcc.gov/Daily_Releases/Daily_Business/2017/db0907/DOC-346584A1.pdf; see also Boley & Byers supra note 29 at 15.

[62] See supra note 30 and accompanying text.

[63] See supra note 29 and accompanying text.

[64] See e.g., Boley & Byers supra note 29.

[65] See supra note 2 at Art. I.

[66] Id. at Art. II. Although FCC regulators are not claiming sovereignty over orbital shells, allowing national companies to saturate them with satellites could constitute appropriation by “other means;” see also supra note 30 (describing the of SpaceX’s mega-constellation in LEO, Koren argues that “the thought of a commercial company’s satellites outnumbering all the rest, and in such a short period of time, is rather astonishing. If extraterrestrial beings were to swing past Earth and check the tags on the artificial objects shrouding the planet, they might think the place belonged to SpaceX”); see also Boley & Byers supra note 29 at 15.

[67] See Boley & Byers supra note 29 at 15. Unlike the FCC’s assignment of GEO orbits, namely, that the assignment be made in a manner that ensures other countries “may have equitable access to those orbits,” no similar regulatory language regarding the assignment of LEO orbits exist. See supra notes 58-61 and accompanying text.

[68] See, e.g., 47 C.F.R. § 1.1306 (2019). There are three exceptions to the FCC’s lack of NEPA review for commercial satellite operators. The first exception is when an applicant proposes a communications facility in a certain location, such as a designated wildlife preserve. The second exception is when an applicant proposes a communications facility that would use high-intensity lighting near a residential area. The third exception is when an applicant proposes a communications facility that would expose humans to radio-frequency radiation above the FCC’s designated safety standards. As such, the FCC considers all satellite mega-constellations, in a most conclusory fashion, as categorically exempt from NEPA review. Id. at § 1.1306(b)(1); § 1.1307(a); § 1.1306(b)(2); § 1.1307(a); § 1.1306(b)(3); see, e.g., Ryan supra note 32 and accompanying text. Since 1986, the FCC considers commercial satellite projects as “categorically excluded” from NEPA review. Id; see, e.g., JASON Report, Mitre Corp., The Impacts of Large Constellations of Satellites (2021), available at https://www.nsf.gov/news/special_reports/jasonreportconstellations/JSR-20-2H_The_Impacts_of_Large_Constellations_of_Satellites_508.pdf. JASON was asked by the National Science Foundation and Department of Energy to assess the possible growth and impact of future mega-constellations on orbital debris. In addition to assessing the likely increased orbital debris resulting from mega-constellations in LEO, JASON was also asked to assess mega-constellation impacts on optical astronomy generally, infrared astronomy, radio astronomy, cosmic microwave background studies, and laser guide-star observations. Id. Noting that the only real FCC regulations that constrain the growth of mega-constellations regard the availability of radio spectrum, and arguing that the FCC’s 2020 orbital debris guidelines, which are only requirements for disclosure rather than mandated thresholds, JASON concluded that FCC regulations fail to effectively mitigate orbital debris in LEO and “fall well short of what the FCC evidently thinks are required for safe traffic management in space …”. Id at 101-2; see also supra note 29 and accompanying text.

[69] See Benjamin Silverstein & Ankit Panda, Space is a Great Commons. It’s Time to Treat it as Such, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 9, 2021, available at https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/03/09/space-is-great-commons.-it-s-time-to-treat-it-as-such-pub-84018 (arguing that the U.S.’s failure to manage LEO orbits as a commons undermines safety and predictability in a manner that exposes space operators to growing risks, such as collisions with other satellites and orbital debris).

[70] See In the Matter of Space Exploration Holdings, LLC, FCC 21-48 (April 23, 2021) https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-21-48A1.pdf (discounting arguments against their approval of SpaceX’s Starlink mega-constellation project that increasing the density of satellites in LEO will increase the amount of orbital debris, which negatively impacts the human environment in a manner that triggers the applicability of NEPA, the FCC argued that “[w]ithout deciding whether such alleged impacts in space are even within the scope of NEPA (which applies to effects on the quality of the human environment),” satellite mega-constellations are “categorically excluded” from NEPA’s environmental review process). Id at 50.

[71] See supra note 29 and accompanying text.

[72] Id; see also JASON Report supra note 68 and accompanying text. The worst known space collision in history took place in February 2009 when the U.S. telecommunication satellite, Iridium 33, and Russia’s defunct military satellite, Kosmos-2251, crashed at the altitude of 490 miles. The incident spawned over 1,000 pieces of debris larger than 4 inches. Many of these fragments were then involved in further orbital incidents. See Leonard David, Effects of Worst Satellite Breakup in History Still Felt Today, January 28, 2013, available at https://www.space.com/19450-space-junk-worst-events-anniversaries.html.

[73] See supra note 2.

[74] See infra supra note 6 and accompanying text.

[75] Howard A. Baker, Space Debris: Legal and Policy Implications 25, 79 (1989). The Liability Convention established a basic framework of tort law applicable to space activities and was a response to concerns about the danger that space objects pose on Earth as they re-enter the atmosphere. Damage caused by space objects while they are in space, however, did not motivate the formation of the Liability Convention, which explains why terrestrial damage has a stricter liability scheme under the Liability Convention than does damage that occurs in space. Id.

[76] See Liability Convention supra note 6. at Art. III.

[77] See Baker supra note 75 at 85-86.

[78] See supra note 8.

[79] See supra note 61.

[80] See supra note 30 and accompanying text.

[81] See supra note 29 and accompanying text.

[82] See supra note 2 at Art. I; Id. at Art. II; Id at Art IX (prohibiting “potentially harmful interference with activities in the peaceful exploration and use of outer space”). Id.

[83] See supra note 60.

[84] See discussion infra Part II.

[85] But see supra note 70 and accompanying text.

[86] See supra note 32 and accompanying text; see also discussion infra Part IV, A.

[87] See https://docs.fcc.gov/public/attachments/FCC-20-54A1.pdf; see also, Federal Register, 85, 165, 52422, & 52455.

[88] See supra note 29 and accompanying text; see also supra note 59 and accompanying text.

[89] See, e.g., JASON Report supra note 68 and accompanying text.

[90] Id at 101-2.

[91] See supra note 20 at 1334.

[92] See David, supra note 22.

[93] Id.

[94] See Caleb Henry, Iridium Would Pay to Deorbit its 30 Defunct Satellites — for the Right Price, SpaceNews, December 30, 2019, available at https://spacenews.com/iridium-would-pay-to-deorbit-its-30-defunct-satellites-for-the-right-price/.

[95] Id.

[96] At current launch prices, $10,000 would barely be enough to launch several pounds of fuel, let alone a spacecraft. Id.

[97] Id. Desch went on to note that his $10,000 price point suggestion was “intentionally provocative and for thought purposes.”

[98] See supra note 46.

[99] See Starlink Pre-Order Agreement, available at https://www.starlink.com/legal/terms-of-service-preorder.

[100] As Mars is considered a “celestial body” under the OST, the OST applies to Mars. See supra note 2 at Art. I, II, III, VI, and VIII; see also Antonio Salmeri, No, Mars is Not a Free Planet, no Matter What SpaceX Says, SpaceNews, December 5, 2020, available at https://spacenews.com/op-ed-no-mars-is-not-a-free-planet-no-matter-what-spacex-says/.

[101] See supra note 46 and accompanying text.

[102] See supra note 2 at Art. II; Id at Part Two, A; see also supra note 29 and accompanying text; see also supra note 59 and accompanying text; see also generally Kessler & Burton, supra note 40.

[103] See supra note 32 and accompanying text.

[104] Id; see also Scientists’ Inst. for Pub. Info., Inc. v. Atomic Energy Comm’n, 481 F.2d 1079, 1088-89 (D.C. Cir. 1973).

[105] See Beattie v. United States, 756 F.2d 91, 99 (D.C. Cir. 1984).

[106] See NEPA, supra note 32 at § 4332(F) (requiring support for international efforts to prevent environmental degradation); see also Lawrence Gerschwer, Informational Standing Under NEPA: Justiciability and the Environmental Decisionmaking Process, 93 Colum. L. Rev. 996, 1000-1008 (1993) (describing procedural process for NEPA review). It is long established that federal agencies must analyze impacts that are caused by proposed federal actions, even if the impact will be felt in “the global commons outside the jurisdiction of any nation.” See Exec. Order No. 12,114, § 2-3(a), 44 Fed. Reg. 1957 (Jan. 4, 1979).

[107] An EA is a “concise public document” that provides evidence and analysis as to whether the agency’s action will have a significant impact on the environment. See 40 C.F.R. § 1508.9(a)(1).

[108] See Greenpeace v. Stone, 748 F. Supp. 749, 766 (D. Haw. 1990) (holding certain circumstances may require application of NEPA to programs abroad); Sierra Club v. Adams, 578 F.2d 389, 392 (D.C. Cir. 1978) (refusing to decide issue of NEPA’s extraterritorial application according to impacts within United States); Environmental Defense Fund v. Massey, 986 F.2d 528, 530-31 (D.C. Cir. 1993) (stating NEPA should be interpreted broadly).

[109] 42 U.S.C. § 4332(C) (2018); 40 C.F.R. § 1508.4 (2019). A categorical exclusion is a “category of actions which do not individually or cumulatively have a significant effect on the human environment.” Id. at § 1508.4.

[110] See Massey, supra note 108 at 532 (finding NEPA applicable when a federal action’s environmental impacts affect more than one nation).

[111] See Bird, supra note 23 at 674-5; see generally Shackelford, supra note 23 (arguing that outer space is best considered a global commons in the same manner as is the deep ocean seabed); see e.g., supra note 69 and accompanying text. In support of considering outer space as a global commons, Silverstein & Panda argue that:

[t]raditionally, commons are areas beyond state dominion that host finite resources available to all (like the oceans) or that provide non-excludable global benefits (like the atmosphere). Outer space is no different … the only natural resource in near-Earth space is the volume of Earth orbits themselves. Space is available for all to use, and states and commercial enterprises use satellites in Earth orbits to deliver agricultural, educational, financial, and security benefits to communities around the globe … . New conventions or regulatory mechanisms for governing Earth orbits will not appear overnight, but states can build toward these goals by clarifying their commitments to treat space as a commons and pursuing governance arrangements that reflect this commitment. New policies in the United States should reflect that Earth orbits are a great commons.

Id.

[112] See supra note 71 and accompanying text; see also Ryan supra note 32 and accompanying text.

[113] See e.g., supra note 70 and accompanying text; see also supra note 68 and accompanying text; see also Ryan, supra note 32 at 938 (detailing the courts’ treatment of the type of conclusory findings that the FCC provided in its review of SpaceX’s Starlink mega-constellation project, Ryan argues that “the goal of examining the cumulative impacts of a project is to prevent an actor from engaging in an activity that has a minimal impact on the environment but, when combined with the activity of other actors, results in a significant impact on the environment”). See Friends of the Earth, 109 F. Supp. 2d at 41 ((citing Nat. Res. Def. Council, Inc. v. Hodel, 865 F.2d 288, 297 (D.C. Cir. 1988)). The court went on to argue that “[c]onclusory remarks … do not equip a decisionmaker to make an informed decision about alternative courses of action or a court to review the Secretary’s reasoning.” Id. (citing Hodel, 865 F.2d at 298). Accordingly, when a federal agency argues that its actions have no significant environmental impact, as the FCC argued regarding its review of the Starlink mega-constellation, without providing supporting evidence for this argument, these arguments may be rejected by the court. Id. at 42.

[114] See supra note 70 and accompanying text. Under the provisions of the OST, every nation has a stake in outer space. See supra note 2 at Part Two, A.

[115] See supra note 2 at at Art. I.

[116] Id. at Part Two, A.

[117] Id. at Art. II.

[118] Id. at Art. VI.

[119] See Jeff Foust, Rocket Lab to Launch Astroscale Inspection Satellite, SpaceNews, September 23, 2021, available at https://spacenews.com/rocket-lab-to-launch-astroscale-inspection-satellite/ (describing current company projects to remove orbital debris); see also Masunaga supra note 64 (detailing private efforts to develop orbital debris removal technology); see also generally, Akhil Rao, Matthew G. Burgess, & Daniel Kaffine, Orbital-Use Fees Could More Than Quadruple the Value of the Space Industry, 23 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117 (2020); J. Pearson, J. Carroll, E. Levin, & J. Oldson, Active debris removal: EDDE, the ElectroDynamic Debris Eliminator in Proceedings of 61st international astronautical congress (2010).

[120] See e.g., NASA Office of Inspector General, supra note 31 at 16. Detailing the conditional effectiveness of voluntary orbital debris mitigation guidelines, the report notes that:

…at the February 2020 United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space meeting in Vienna, Austria, the United States urged all spacefaring nations, emerging space nations, international organizations, and non-government organizations to implement orbital debris mitigation guidelines to limit the generation of debris. However, adopting voluntary guidelines does not ensure compliance, as demonstrated when China and India—both signatories of the Inter-Agency Debris Coordination Committee—conducted their anti-satellite tests in 2007 and 2019, respectively, resulting in the creation of additional orbital debris. At a September 2020 congressional committee hearing, NASA’s Administrator commented, “… there has been a lot of activity from our international friends who don’t necessarily follow the guidelines. While countries sign on to the guidelines, it does not necessarily mean they fully adhere to the guidelines.”

Id.

[121] Id; see also Jamie Morin, Four Steps to Global Management of Space Traffic, Nature, March 5, 2019, available at https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-00732-7; see also Jeff Foust, Space Force Backs Development of Commercial Orbital Debris Removal Systems, SpaceNews, September 15, 2021, available at https://spacenews.com/space-force-backs-development-of-commercial-orbital-debris-removal-systems/ (describing efforts by the United States Space Force to support the development of private sector solutions that address the growing problem of orbital debris); see also supra note 87.

[122] See supra note 20; see also, e.g., supra note 25 and accompanying text; Khatchadourian supra note 40. Quoting Chris Blackerby, Chief Operations Officer of Astroscale, the world’s first private orbital debris removal company on the incentive structure of satellite operators, Khatchadourian writes:

“[w]e recognize the operators don’t see a current impetus to bring [their debris] down … ”. “One of the problems is, when does the price point for paying for the removal of the debris reach the level in the minds of those operators that it’s worth it to mitigate that risk?”

Id; see supra notes 94-97 and accompanying text; see also discussion infra Part III.

[123] See Rao et al., supra note 119, at 12756.

[124] Id.

[125] See supra note 2 at Art. II.

[126] See Liability Convention supra note 6. at Art. III; see also Baker supra note 75 at 85-86.

[127] See Rao et al., supra note 119 at 12756; see also supra notes 94-97 and accompanying text; discussion infra Part III.

[128] This dynamic will likely doom outer space to Garrett Hardin’s seminal 1968 formulation of the tragedy of the commons: “[r]uin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own best interest.” Garrett Hardin, The Tragedy of the Commons, 162 Science 1243, 1244 (1968); see also Setting Barry C. Field & Nancy D. Olewiler, Environmental Economics 64-81 (1995) (explaining the international tragedy of the commons in pollution); see also supra note 20 and accompanying text; David, supra note 29 and accompanying text; Muñoz-Patchen, supra note 23; see also Matthew Weinzierl, Space, the Final Economic Frontier, J. Econ Perspect. 32, 173–192 (2018); Alexandra Witze, The Quest to Conquer Earth’s Space Junk Problem, Nature 561, 24–26 (2018); Nodir Adilov, Peter J. Alexander, & Brendan Michael Cunningham, Earth Orbit Debris: An Economic Model. Environ. Resour. Econ. 60, 81–98 (2015); see also discussion infra Part IV, A.

[129] See supra note 2 at Art. VI.

[130] See e.g., Rao et al., supra note 119. Based on the calculations in this study, which focuses on the source of the externality, the object in orbit:

the optimal OUF starts at roughly $14,900 per satellite-year in 2020 and escalates at roughly 14% per year (aside from some initial transition dynamics) to around $235,000 per satellite-year in 2040. Rising optimal price paths are common in environmental pricing such as carbon taxes… although declining optimal price paths are also possible. The rising price path in this case partly reflects the rising value of safer orbits … [resulting] from the OUF. For comparison, the average annual profits of operating a satellite in 2015 were roughly $2.1 million. The 2020 and 2040 OUF values we describe amount to roughly 0.7 and 11% of average annual profits generated by a satellite in 2015.

[131] See NASA Office of Inspector General, supra note 31. Regarding the U.S. government’s funding need for orbital debris removal projects, NASA argues that: