As the company’s information treasure trove grew, two things were clear: With more information in more places, with more value, traveling across the globe at the speed of light, something bad was eventually bound to happen. And the consequences of failing to manage information assets began to have greater implications for stock value, reputation, executive’s careers, customers, regulators, courts, and the court of public opinion.

The US Department of Justice recently updated its “Evaluation of Corporate Compliance Programs,” which guides prosecutors and courts in the adequacy and effectiveness of a corporation’s compliance program. Implicit in a good compliance program is that companies can’t babysit all their employees all day, every day. But if a company constructs an artifice to help employees comply with company policy, for example, the consequences of failure may be reduced or nothing at all. In that sense, good compliance is like insurance—you may never need it, but it provides solace just knowing it exists and is good. So, knowing the criteria a company may be evaluated against someday should help it bolster its corporate compliance programs. More specifically, this article is about information governance compliance programs that are becoming increasingly important with corporate information growing at 23% each year (per IDC), the increase in privacy regulations, and the adoption of big data projects.

We live in a world that requires companies to use data to better to understand their customers’ needs, improve products and services, reduce costs, and improve business efficiency, all while complying with laws and regulations that dictate how long information must be retained among other things. According to The Economist, data is one of the most valuable resources in the world today.

| ABBYY recently polled thousands of office workers across the globe, and found that 64% of UK employees have difficulty accessing data. In fact, a quarter (27%) lose a full day of productivity every week (ABBYY). |

Organizations are generating as much as 7.5 septillion gigabytes of data per day, which is why laws and regulations that govern the management of data are increasing. To put that in context, we create roughly the data equivalent of 50,000 years of continuous movies every few hours, all day, every day. Now more than ever you should consider creating or reviewing your information governance policies and practices to ensure they address the information your organization generates, receives, and manages. This might sound like a daunting task, but it doesn’t have to be.

Let’s start with defining information governance: It is the management, retention, and disposition of information that an organization creates and collects. Information is the lifeblood of most companies today and should be managed as a valuable asset. Given the overlapping influences of contractual obligations, preserving customer trust, and laws and regulations, companies can’t afford to ignore information governance.

Many confuse information governance with records management, but there is a huge difference. Traditional records management compliance programs typically had policies that outlined the official records (purchase orders, personnel files, contracts, etc.) that needed to be retained in accordance with laws and regulations and business needs. Typically, most programs had “minimum” retention periods established to ensure records were not disposed of too quickly in case a regulator wanted to inspect them. Addressing official records by imposing a minimum retention is no longer considered reasonable or good enough. Instead, companies must govern all information that the organization generates, receives, and manages regardless of the medium or storage location (e.g., onsite, AWS, SAS provider, mobile device) and if it is the official record or not. For most organizations, a vast amount of information that is under their management may not have any law or regulation mandating its retention or disposal and may have short-term business value. This vast amount of information requires governance and management, too. It must have a predictable end of life, especially if it contains high-risk data.

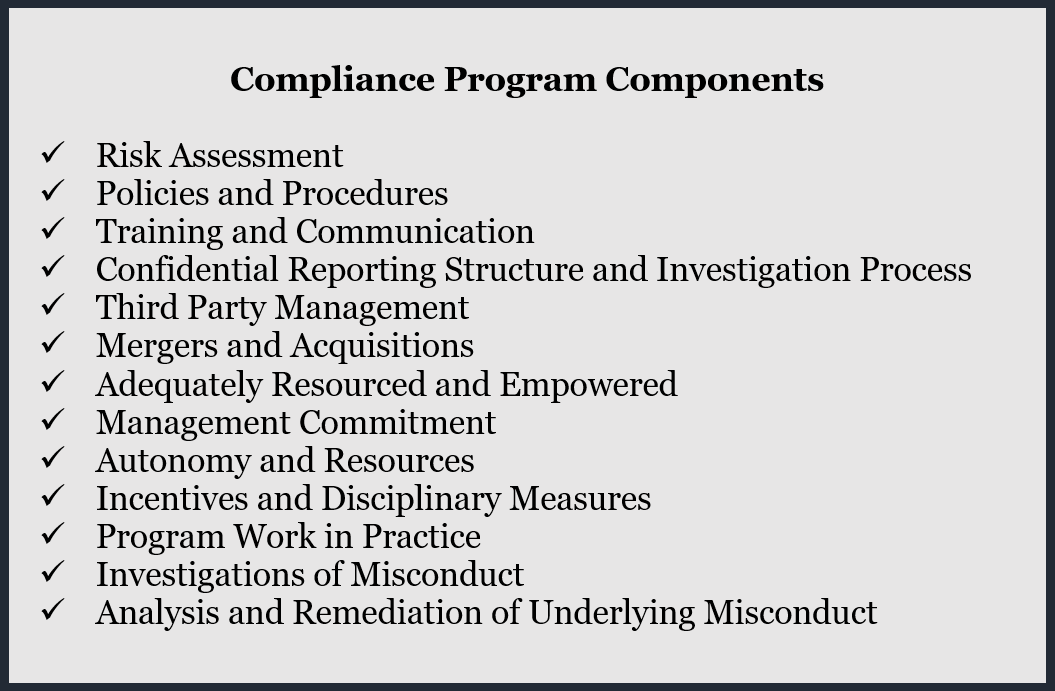

Over two decades ago, the Kahn Consulting firm developed the Seven Keys to Information Management Compliance based on Federal Sentencing Guidelines. The Seven Keys takes the Federal Sentencing Guidelines and adapts them for the information space. The Department of Justice guidance to prosecutors can be used as a roadmap to implement or validate the key components of your company’s information governance compliance program. Summarized below is a roadmap to implement or augment your compliance programs, focusing specifically on information governance.

Summary of Roadmap

1. Risk Assessments

A compliance program’s key components should consist of a risk assessment process to identify, analyze, and address particular risks. This process should be documented and consist of metrics that will be used to address compliance. Based on the risk profile, there should be resources, funding, and scrutiny allocated appropriately based on the level of risk. Risk assessments should be conducted routinely and based upon operational data.

Actions taken to address risk (policy modifications, training, etc.) should be documented and monitored. The risk assessment process should incorporate lessons learned from actions taken within the company and other companies with similar business profiles. As it relates to information governance, a risk assessment should include structured information, unstructured information, third parties storing information, outsourced business processes that have an information component (i.e., benefits, 401(k), retirement), communications and messaging environments, end user productivity environments such as Microsoft 365 and Google Workspace including collaboration and meetings, robotic generated data, etc.

2. Policies and Procedures

Policies and procedures must be part of a well-designed compliance program. Policies and procedures should address identified risks and directives that must be followed, as well as strive to establish a culture that promotes compliance. The company should have a policy management process in place that dictates how corporate policies should be designed, approved, published, implemented, and maintained over time. Information management policies and procedures should address the retention of information (records and non-records), disposition rules, preservation obligations, and protection of specific classes of information.

3. Training and Communications

A key component of a well-designed compliance program is the training of employees and the communications used to integrate the policies within the company. Training and communication messages should be tailored for specific audiences. High-risk areas may require more training and/or more detailed examples during training. The training should take into consideration the form and language(s) that are used. Training should be an ongoing activity and incorporate lessons learned from past noncompliance events. Communications should include the leadership’s position on misconduct or non-compliance (i.e., warning, termination, discipline). Training and communications should provide guidance for employees to identify when they should seek assistance and where they can get that assistance.

Information management programs should have an annual required training program, and periodic communications should be sent out from senior leadership reminding the organization of the value of information and the potential risk of non-compliance with policies and procedures. Furthermore, training and communications should be targeted for specific audiences such as application owners, Google Workspace users, network/fileshare users, email users, third-party contract business owners, etc. The messages and training must be specific to the actions that are required. For example, if the company’s policy is to purge email after one year, define the specific action that must be taken in the rare event that an email would rise to the level of a record requiring longer retention.

4. Confidential Reporting Structures and Investigation Processes

Confidential reporting structures and investigation processes are essential in compliance programs. Employees must be able to report non-compliance and misconduct anonymously and confidentially. The company’s culture and processes should promote and measure the workplace environment to ensure that fear of retaliation doesn’t exist. Processes need to route issues quickly to a few, appropriate people so they may be dealt with in a timely manner. Employees must be made aware of how to report non-compliance and what happens once they report it. There should be a robust process including metrics, to investigate, manage, and discipline non-compliance.

The information gathered during non-compliance should be tracked, analyzed, and used for lessons learned. Information governance non-compliance can have serious consequences to the organization. The over-retention of private information can have reputational damage and financial consequences. Destruction of potentially relevant information that has been placed on a legal hold may not only cause fines and penalties but may also impact the outcome of litigation or a regulatory investigation.

5. Management of Third-Party Relationships

Third-party relationships should include a strong risk-based diligence process. The diligence should be appropriately aligned with the level of risk. As part of the risk assessment, sub-contractors to the third party should be assessed, and contract terms and conditions should be reviewed. Ongoing monitoring of the third-party relationship should be documented, audited, and tracked. Specifically related to information governance, any third party storing, managing, or accessing information on behalf of your company should have a risk assessment completed. Third parties with personal information, highly confidential information, or IP should have additional scrutiny and corresponding controls established.

Real actions and consequences need to take place when non-compliance exists. Follow up to non-compliance is required to ensure that the third party has addressed the issues. As it relates to information governance, all contracts should clearly identify the third party’s roles and responsibilities as they relate to retention, disposal, and preservation of information, including the redaction or anonymization of personal information.

6. Mergers and Acquisitions

Mergers and acquisitions need to be included in a well-designed compliance program to ensure timely and orderly integration of any acquired entity into the company’s compliance regime. Divestitures need to be evaluated to ensure the appropriate compliance activities are moved to the acquiring company in a timely manner. There should be a due diligence process, integration process, and implementation plan prepared prior to the actual transaction taking place. Information governance responsibilities need to be clearly outlined so the segregation of information can take place, claw-back clauses can be incorporated into contracts as necessary, and information related to open litigation, audits, or investigations can be addressed. Identification of all the information that is impacted by an acquisition or divestiture is becoming more complex as it relates to big data projects, privacy laws, and the expanding number of third parties storing the information.

7. Adequate Resources and Empowerment

Companies must adequately resource and empower their compliance programs. Issuing policies is no longer good enough. Compliance programs must have implementation plans to ensure appropriate staffing is in place to audit, document, analyze, and continuously improve compliance programs. This key component can be time-consuming when it comes to information governance compliance programs.

A few examples of areas requiring automated or manual plans for managing information are: applications, third parties managing information on the company’s behalf, end user information storage locations, communication systems, and off-site storage boxes. You should automate as much as you can, but there are realities where rules cannot be automated and will require manual intervention. Implementation cannot start until the company develops and enacts a documented retention schedule that outlines the rules for retaining specific categories of data. The retention schedule needs to be based on up-to-date legal research for each jurisdiction where the company conducts business. It must also address the business value of the information.

8. Commitment from Senior and Middle Management

For a compliance program to be successful, senior and middle management commitment and messaging is a necessity to foster a culture of compliance within the company. The C-suite and the board set the tone for the rest of the organization by messaging the importance of compliance and by demonstrating adherence. All leaders in the company need to take ownership and accountability for their employees when it comes to monitoring and checking for compliance with policies. When management finds non-compliance, management needs to address the matter and perhaps use it as a teaching moment for the rest of the staff.

9. Autonomy and Effective Resources

Program autonomy and effective resources are essential in a well-designed compliance program. Compliance programs need to have day-to-day oversight, and those responsible for that oversight must have adequate autonomy authority, seniority, and access to the Board of Directors. Team members should have the appropriate experience to address non-compliance issues. Internal audits should also be conducted to ensure that compliance personnel are in fact empowered and positioned to detect and prevent non-compliance. As for information governance programs, there should be a governance board that is represented by Legal, IT, Security, Privacy, Compliance, Audit, and select business units.

10. Incentives for Compliance and Disincentives for Non-Compliance

Implementation of a compliance program should consist of incentives for compliance and disincentives for non-compliance. Clear disciplinary procedures should be in place, consistently enforced across the organization, and commensurate with the violations. Communications from senior leadership should inform employees that unethical conduct and policy violations will not be tolerated and will have consequences. A company can consider implementing an incentive system that rewards compliance and ethical behavior. Information governance programs should be treated as equally as important as other compliance program.

11. Proof that the Compliance Program Works in Place

A compliance program should have the ability to prove that is it working, and more importantly, that it was working when a violation occurred. Documentation and evidence of actions taken is important—always document how a misconduct was detected, how the investigation was conducted, what resources participated in the investigation, and the remediation efforts. The compliance program should also document how the program has evolved over time and maintain an audit trail of changing risks and continuous improvements to the program to address new risks or non-compliance issues. The following should be part of a well-designed compliance program to prove that the program was working at the time of a non-compliance event:

- Continuous Improvement, Periodic Testing, and Review: An effective compliance program must have the ability to improve and evolve.

- Internal Audit: Internal audits must have a rigorous process that is followed and routinely conducted.

- Control Testing: Testing controls should be established, and collection of compliance data must be routinely collected and analyzed, and necessary actions taken.

- Evolving Updates: Risk assessments, policies, procedures, practices should routinely be improved to reflect the current risk profile and based on lessons learned.

- Culture of Compliance: Companies should routinely measure their culture of compliance through all levels of the organization.

12. Investigations of Misconduct

All examinations of allegations and suspicions of misconduct by the company, its employees, or third-party agents must work effectively and be appropriately funded to ensure a timely and thorough investigation that includes a documented response of its findings, disciplinary actions, and remediation measures. Investigations must be conducted by an objective party. For information governance compliance, automating monitoring for non-compliance should be considered. As an example, monitoring the volume of data leaving your organization can be an indication of an employee transferring data to a private account outside of the company. You can use tools such as MS 365 to both automate compliance and detect non-compliance. After evidence determines a questionable act, people, process, and technology should be in place to assess the alleged infraction and take necessary action.

13. Analysis and Remediation of Any Underlying Misconduct

Lastly, a well-designed compliance program that is working in practice must have a thoughtful root cause analysis of misconduct, and the company must timely and appropriately take action to remediate the root cause. Root cause analysis should consider what control failed (policy, procedure, training, etc.), the amount of funding provided, what vendors were involved, any prior indications of failure, what prior remediation efforts were taken to address a similar compliance issue, and any failures in supervision of employees. Information governance compliance often finds failures in generalized “off-the-shelf” training programs. Training programs must be 100% aligned with policy directives, practices, and procedures. Employees need to clearly understand where they are allowed to store certain types of information and how disposal of the information will happen in accordance with policy and business unit or IT practices and procedures.

Summary

Now more than ever, companies need to make an honest effort to do the right thing and comply with laws and regulations. However, in the event that employees or third parties managing data on your company’s behalf inadvertently (or intentionally) violate a law or regulation, a well-designed information governance compliance program can be used to demonstrate “reasonableness” and the company’s good faith efforts to comply with laws and regulations, which ultimately may be the difference between winning and losing.