With SPAC IPOs virtually gone but SPAC mergers (aka de-SPACs) continuing at a steady pace since the beginning of the year, the questions around getting a deal done boil down to the following:

- How and where can companies get financing now that the PIPE (private investment in public equity) market has dried up?

- How long will it really take to get the deal closed, now that target companies are not easy to come by and every deal seems to need an extension?

- How can the current litigation and regulatory risks be avoided, or at least minimized?

In this article, we’ll focus on the third question, examining how the litigation and regulatory risk for SPACs has shifted since our 2022 year-end report.

SPAC Litigation by the Numbers

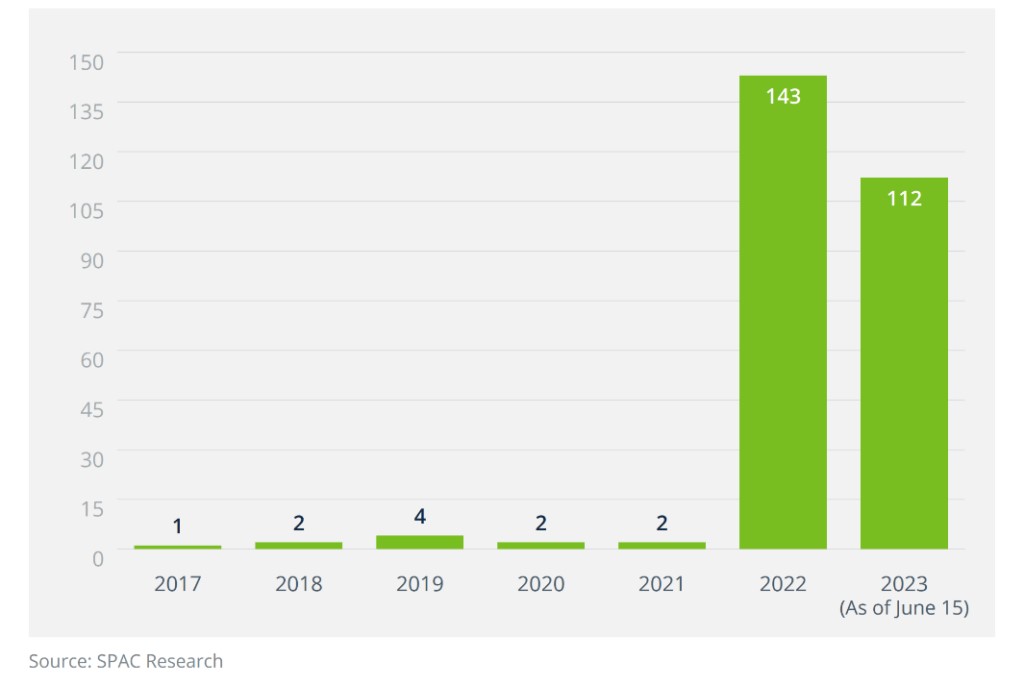

Through June 15, 2023, five SPAC-related securities class actions (SCAs) have been filed so far this year. That is not a high number. With 33 total SCAs filed in 2021 and 24 in 2022, we are at a slower pace for securities class actions this year than in the previous two years.

Filed SPAC/de-SPAC Securities Class Actions.

Examining the data between January 1, 2021, and June 15, 2023, it takes, on average, 12.82 months after the merger (aka de-SPAC) for an SCA to be filed. Except for a handful of cases, most lawsuits are filed after the de-SPAC has been completed. Considering that there were 199 de-SPACs in 2021, 102 in 2022, and 35 as of June 15, 2023, the downward progression of the number of SCAs this year tied to the downward progression of de-SPACs is not surprising. But that downward progression is somewhat deceptive.

Number of Suits vs. Number of Closed de-SPACs.

Direct Cases Picking Up Steam in Delaware

What the SCA data does not show is the growing number of direct-action breach of fiduciary duty suits being brought in Delaware. These suits are a progeny of the MultiPlan case in which the Delaware Chancery Court denied the defendants’ motion to dismiss. The parties subsequently settled for $33.75 million in November 2022, and no one in the SPAC world was surprised to see plaintiffs in other cases, including at least three so far in 2023, take a similar route.

Direct cases like MultiPlan and a few news-making examples below are easier to bring because, unlike derivative cases, they do not need to go through an extra step of satisfying demand futility requirements. It is no wonder then that, spurred by several denials of the defendants’ motions to dismiss and an easier procedural hurdle, plaintiffs’ attorneys are trading their SCA strategies for direct fiduciary suits against Delaware SPACs.

Examples of Direct Breach of Fiduciary Duty Suits

Lawsuit | Suit Filed | Outcome | Amount of Settlement |

MultiPlan | January 24, 2021 | Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss Denied – January 3, 2022 | $33.75 Million |

GigAcquisitions3 | January 4, 2021 | Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss Denied – January 4, 2023 | Unknown |

GigAcquisitions2 | September 23, 2021 | Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss Denied – March 1, 2023 | Unknown |

Trident Acquisitions Corp/Lottery.com | April 3, 2023 | TBD | Unknown |

Lordstown Motors | December 13, 2021 | Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss Withdrawn | Unknown |

Source: Woodruff Sawyer

From the perspective of directors and officers (D&O) insurance coverage, claims from direct suits, while typically indemnifiable, are not covered by “Side A only” D&O coverage. Many SPAC D&O insurance programs are structured as traditional “ABC” programs that would offer coverage for claims coming out of a direct suit. However, some SPAC teams, as a cost-saving alternative at the peak of the SPAC craze in 2021, when D&O insurance prices were astronomical, chose to structure their programs as Side A only. To the extent that a SPAC purchased a Side A–only policy and the lawsuit is determined, like in MultiPlan, to be a direct one, there may be no D&O insurance response for a settlement (outside of a corporate bankruptcy).

Whose Money Is It Anyway?

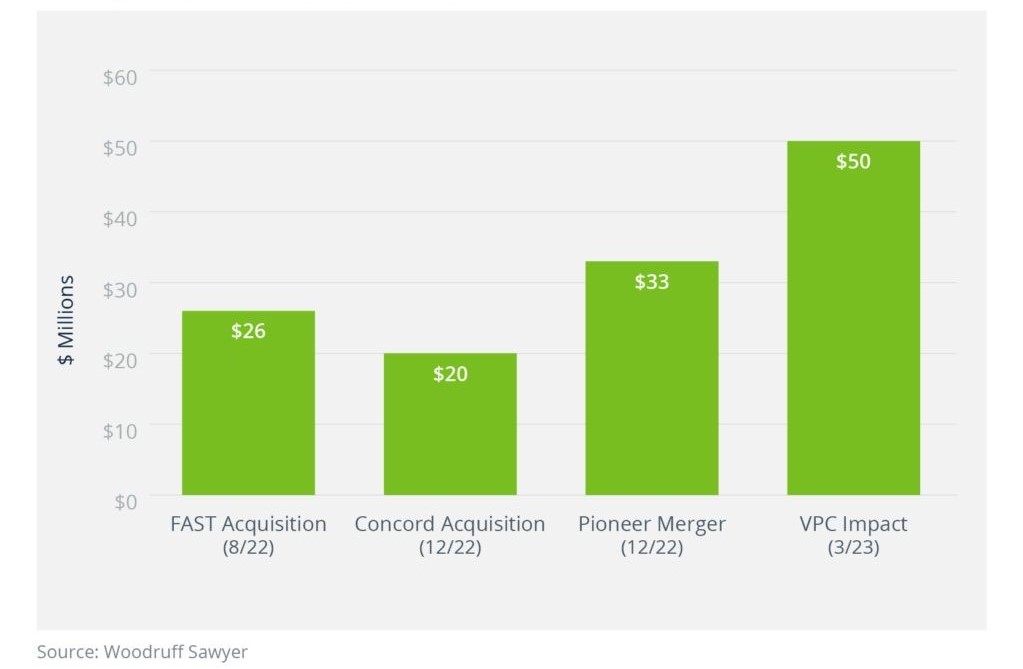

Another interesting trend continuing this year is the series of termination fee cases. In the first of these, the FAST Acquisition Corp. lawsuit from August 2022, the plaintiff investors objected to the SPAC team keeping the entire termination fee it had negotiated without sharing it with its investors. Other similar suits, with a few examples noted below, followed shortly after.

Examples of Termination Fee Suits.

The interesting element of these suits is that they would likely not have been filed had the SPAC team been able to complete a subsequent acquisition. But because the SPAC team failed to do so and had liquidated instead, the plaintiff investors naturally were not pleased to have been left out of the so-called termination spoils.

Considering the recent spike in liquidations as presented in the graph below, it is likely we will see more of these termination fee cases as more SPACs continue to liquidate—that is, unless the SPAC teams take note of this development and start approaching the apportionment of the termination fee differently.

SPAC Liquidations.

SPAC Wins

Not all SPAC-related cases came out on the side of the plaintiffs. There are several notable and interesting SPAC “wins”—decisions that went in the defendant’s favor. A few examples are:

- Diamond Eagle Acquisition Corp/DraftKings: In January 2023, the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York (SDNY) granted the defendants’ motion to dismiss this SCA. The court held that the plaintiffs’ suit relied entirely on a short seller report with unknown sources, the claims in which were not adequately supported by independent research. As a result, plaintiffs failed to sufficiently allege that (1) any violations or material misstatements were made by the defendants and (2) any defendant acted with scienter as required under the law.

As a side note, about 35% of all SPAC-related securities lawsuits involve allegations from a previously published short-seller report.

- Churchill Capital Acquisition Corporation IV/Lucid Motors: In January 2023, the Northern District of California granted the dismissal of the SCA on the grounds that the plaintiffs failed to plead materiality because they had no reason to know in early 2021 that the SPAC would merge with Lucid, as the parties were not engaged in merger discussions.

- CarLotz: In March 2023, the SDNY dismissed the SCA assertion against CarLotz and certain directors and officers for plaintiffs’ lack of standing related to allegations of pre-merger statements. The court held that the investor plaintiffs failed to allege that they purchased shares traceable to the registration for the merger transaction.

Settlements

Let’s turn from lawsuits to settlements. There have been very few publicly disclosed settlements, so it is difficult to draw conclusions about trends. The ones that made the news are listed in the graph below.

Of particular interest are the amounts of some of those settlements that were covered by D&O insurance policies. Insurance coverage information is rarely publicly available, so it is possible, and even likely, that other settlements noted in the chart were also at least partially backed by D&O insurance payouts.

![A bar graph shows SPAC litigation settlements have ranged from $3 million for Ability Inc. in 2019 to $35 million for Akazoo (2021) and $33.75 million for MultiPlan (2022). Information on insurance coverage is limited, but insurance covered $4.25 million of $9 million for Triterras [2022]; $4 million of $8.5 million, Momentus [2023]); and $19.5 million of $22 million (Clover Health [2023]). Source: Woodruff Sawyer.](https://businesslawtoday.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Cropped-Litigation-Settlements_SPAC-Litigation-Mid-Year-Update.jpg)

Litigation Settlements.

It’s worth remembering that outside of the actual settlement amounts, the defendants also had to pay substantial attorney fees. When deciding on the limit of a D&O policy, it’s worth factoring in the potential costs of the attorney fees, which will be due whether the lawsuit ends up being frivolous or ultimately gets dismissed.

Regulatory Enforcement Actions

Regulatory enforcement actions and investigations are, of course, the other piece of the risk puzzle. With the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) taking an openly hostile stance towards SPACs, many of us expected to see a barrage of SPAC-related investigations and enforcement actions. That expectation continues to be unrealized. While rumors are that the SEC is quite busy launching SPAC-related investigations, only several have been publicly reported, and we have seen only a handful of enforcements. Here are some examples that made the headlines:

![A bar graph shows settlement and fine totals from $100k (Gordon [CEO], 2019) to $125 million (Nikola, 2021), with most examples included between $1 million and $8 million. Source: Woodruff Sawyer.](https://businesslawtoday.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Cropped-Regulatory-Enforcement-Settlements-and-Fines_SPAC-Litigation-Mid-Year-Update.jpg)

Regulatory Enforcement Settlements and Fines.

Some additional details on the settlements and fines listed above are as follows:

- Gordon: Administrative charges settled against CEO in January 2019 for $100,000. The SEC charged Benjamin Gordon, the former CEO of Cambridge Capital Acquisition Corporation, a SPAC, with failing to conduct appropriate due diligence to ensure that the SPAC’s shareholders voting on the merger were provided with accurate information concerning the target’s business prospects.

- Momentus: Settlement total of $8.04 million in July 2021. The SEC alleged that Momentus and the founder misled Stable Road, the SPAC with which it planned to merge, about its technology and national security issues and that Stable Road had failed to perform its due diligence to identify those issues.

- Nikola: Settlement total of $125 million in December 2021. The enforcement was preceded by a short seller report and an SCA and centered around misleading statements about Nikola’s products, technical advancements, and commercial prospects.

- Perceptive Advisors: Settlement of $1.5 million in September 2022. This case was the SEC’s first enforcement action against an investment adviser. The SEC charged the adviser with violating the Investment Advisers Act in connection with its involvement with SPACs.

- Morgenthau: Forfeiture of $5.1 million, restitution of $5.1 million, and 36 months in prison for the SPAC’s former CFO in April 2023. In January 2023, the SEC brought fraud charges against Cooper J. Morgenthau, the former CFO of African Gold Acquisition Corp., a SPAC. The charges revolved around Morgenthau orchestrating a scheme in which he stole more than $5 million from the company and from investors in two other SPACs that he incorporated.

- Corvex: Settlement of $1 million in April 2023. The SEC charged investment adviser Corvex Management LP with failing to disclose conflicts of interest regarding its personnel’s ownership of sponsors of several SPACs into which Corvex advised its clients to invest. Corvex also agreed to a cease-and-desist order and a censure.

Update on the D&O Insurance Market and Rates

Market Conditions

The above data and trends have real implications on the risk and risk mitigation decisions that SPAC sponsors, their target companies, investors, and deal teams make. Higher risk of litigation or enforcement, for example, yields lower availability of D&O insurance coverage and higher premiums. Overall insurance market trends also dictate the kind of coverage and costs a team should expect.

As we noted at the end of 2022, the impossibly hard SPAC D&O market started to turn. In just a few months since the beginning of the year, we witnessed one of the fastest adjustments in the wider public company D&O market ever recorded.

Many new insurers have joined the ranks and now, with an oversupply of insurance capacity and very few IPOs, insurers are competing for public D&O new and renewal business, driving rates and retentions down for almost all companies. Mature public companies are experiencing significant rate relief, and newly public companies are seeing significant rate decreases due to higher starting premiums.

What This Market Means for SPAC D&O Insurance Rates

The pressure on carriers in the overall public D&O insurance market is good news for SPACs. We are seeing more carriers interested or willing to take a second look at SPAC tails, extensions, and new go-forward programs. Competition is driving premiums down. Self-insured retention benchmarks are also dropping. More carriers are willing to be flexible on the structuring of the coverage.

However, the likelihood of a SPAC-related company getting sued continues to be higher than that of a traditional IPO or a mature public company. Carriers are continuing to keep a very close eye on each new court decision and enforcement action. For example, a recent decision from Delaware led to many carriers being unwilling to renegotiate tail pricing on the SPAC IPO policy or imposing coverage exclusions. Many are still wary of granting long extensions or reducing premium pricing on those extensions.

Our Predictions

As we predicted at the end of 2022, SPACs have enjoyed a period of reasonable D&O insurance pricing so far in 2023, and that will likely continue into 2024. However, SPAC teams and their target companies will need to make some program restructuring decisions (with the help of their insurance brokers) to adjust for the new trends in the direct fiduciary duty cases and other court decisions as they affect D&O carriers’ obligations.

An earlier version of this article appeared in the Woodruff Sawyer SPAC Notebook.