Interested in this article? Consider attending these upcoming events at the ABA Business Law Section Virtual Section Annual Meeting, Monday, Sept. 21–Friday, Sept 25 (Information and Registration HERE.)

·Legal Analytics Program: Measuring Outside Counsel by the Numbers, Thursday, September 24, 9:00AM–10:30AM

·Legal Analytics Committee Meeting, Friday, September 25, 9:00AM–11:00AM CST

Did you know that you can make money investing in other people’s lawsuits?

Over the last decade, alternative litigation finance (ALF)[1]—the “funding of litigation activities by entities other than the parties themselves”—has taken off in the United States, with capital pouring in from “income-starved” investors seeking strong returns largely uncorrelated to public markets.

Despite ALF’s growth and institutionalization, for some, the space remains controversial. Detractors like the U.S. Chamber Institute for Legal Reform argue that it “increases the probability that meritless claims will be brought.” Supporters counter that investors have zero incentive to finance spurious cases and, to the contrary, can provide an important market-sorting function by allocating funds to resource-constrained parties’ meritorious claims while eschewing unviable matters.

In a sense, ALF hits on a core tension underlying our legal system. From a normative perspective, litigation is a system to right wrongs and promote fairness. Yet, descriptively, it is also a vast industry characterized by complex incentives and well-resourced “repeat players,” creating a dynamic that can exacerbate structural inequities.

For lawyers, ALF presents unique challenges implicating both professional responsibilities as well as practical commercial considerations. To help provide guidance, on August 4, 2020, the ABA’s House of Delegates adopted the American Bar Association Best Practices for Third-Party Litigation Funding (Best Practices). The report “surveys the types of alternative litigation funding and proposes best practices to be consulted and factors to be considered by attorneys seeking to explore or utilize litigation funding in dynamic regulatory, judicial, and arbitral environments.”

What Is Alternative Litigation Finance?

The Best Practices report notes that “[a] single narrow definition . . . cannot encompass the range of funding activities that may arise” with respect to ALF, but at its core it “is a form of distributing risk.” In that regard, ALF is not unlike contingent-fee arrangements, which for many plaintiffs represents the primary alternative for pursuing claims.

In 1897, Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote that “[w]hen we study law we are not studying a mystery but a well-known profession. . . . The object of our study, then, is prediction.” In finance terms, this implies that litigation, and thus ALF, is not a matter of Knightian uncertainty (suggesting unquantifiable outcomes) but is fundamentally subject to risk (a set of unknown, but ultimately calculable, outcomes).

Indeed, commercial clients typically come to lawyers with questions best answered in the form of a number: How much can we win (or lose)? What are the odds? How long will it take?

Legal analytics provides the tools for answering such questions, whereas litigation finance offers a vehicle for transferring the now-quantified legal risk to the parties best suited to bear it. Unsurprisingly, the Artificial Lawyer has observed at least four partnerships between legal prediction startups and litigation funders.

ALF transaction structures are complex and vary widely, though the core approach is transferring financial exposure to legal risk while minimizing basis and ensuring strict adherence to the rules of professional responsibility in respect of case control and otherwise.

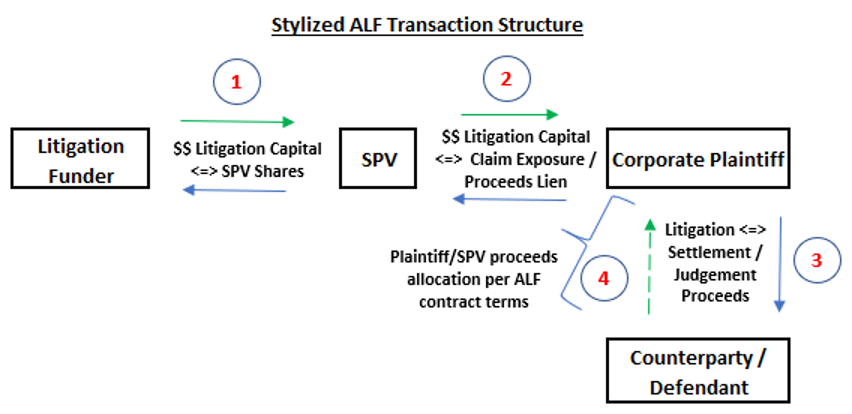

The diagram below presents a simplified example of an ALF deal structure:

The transaction above basically works as follows: (1) a newly created special purpose vehicle (SPV) sells shares to an ALF firm; (2) the SPV uses the capital to purchase exposure to a company’s legal claims (effectively taking them off the cedant’s balance sheet) in exchange for a security interest in the proceeds; (3) using capital from the SPV, the company pursues the litigation; and (4) if successful, the company and ALF firm share in any eventual recovery.

Computationally, though at a highly simplified level, one could think of the expected value of a litigation claim as:

E [Vclaim] ~ = [(p*A) – C] / (1+r)T

where “p” is the probability of an award or settlement, “A” is the amount, “C” is the cost of litigation, “T” is the expected duration, and “r” is the applicable discount rate.

ALF Market

The Best Practices report provides a broad survey of the ALF market, finding that in recent years “[t]he frequency of funding, the diversity of types of funding, and the number of funders have increased,” along with the capital dedicated to the space. Further, “[p]erhaps most importantly, the forms of dispute financing have expanded significantly, raising challenging questions about how ‘third-party funder’ or ‘third-party funding’ should be defined,” as an International Council for Commercial Arbitration report noted.

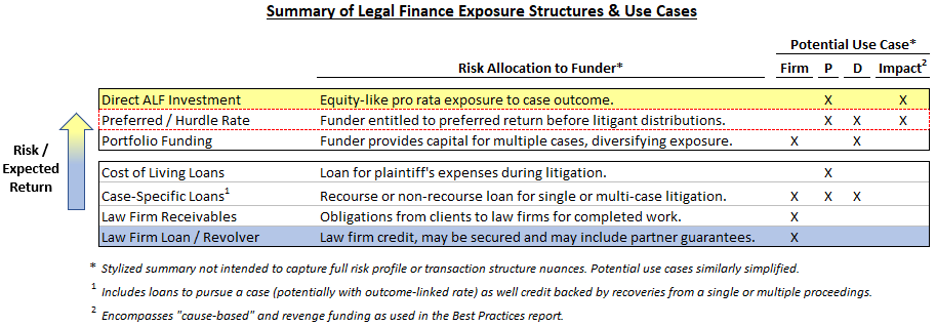

The diagram below summarizes the different ALF types discussed in the Best Practices report through a taxonomy based on the structure of the litigation funder’s financial exposure to the underlying legal risk:

Broadly, the funding types can be grouped between those offering direct exposure to case outcomes and litigation-related credit, where the funder does not necessarily share in the upside, but may have some floor on their exposure through recourse, collateral, or guarantees, such as with respect to law firm loans.

Importantly, first category of outcomes-tied ALF represents the vast majority of the market. At the same time, based on conversations with market participants, the “preferred or hurdle rate” structure, denoted by the red-dotted box, is the most common return structure in the market today.

The key distinction in the above framework is not the use of funds, which are innately litigation related, but the nature of the capital provider’s exposure to the underlying legal asset and potential corresponding implications in respect of case control and the parties’ broader incentives.

ALF Returns and Performance

Based on performance figures, it is not difficult to see why ALF is “booming,” as Businessweek put it. Many ALF funds have reported net internal rates of return exceeding 30 percent, whereas some players, like IMF Bentham (rebranded as Omni Bridgeway), have delivered closer to 60 percent, according to a Bloomberg report. Furthermore, ALF is commonly understood to be largely uncorrelated to broader public markets, making it even more attractive from a portfolio construction perspective.

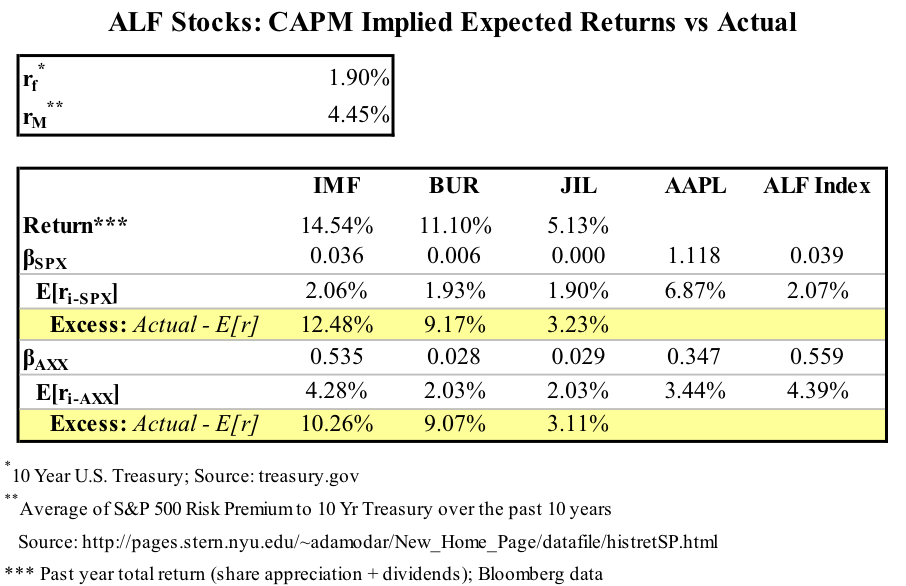

Unfortunately, due to ALF transactions being both private and generally highly illiquid, it is next to impossible to perfectly capture this dynamic empirically. With that caveat, the table below presents one—admittedly, imperfect—approach based on market prices through 2016 for publicly-listed ALF vehicles: Burford, IMF Bentham (Omni Bridgeway) and Juridica. As shown below, the Beta, or level of market exposure against the S&P 500—typically around 1 for most companies and 1.118 for Apple as shown below—is near 0 for the ALF funds.

Consequently, all three ALF firms displayed significant excess returns relative to predictions based on the CAPM model.

Report Recommendations

In part due to ALF’s complexity, the Best Practices report does “not take a position on a number of litigation funding issues” and generally eschews a prescriptive posture. Rather, the report seeks to provide certain broad-based principles “common to all types of funding.” These principles emphasize thorough documentation of the funding arrangement, as well as adherence to the Model Rules of Professional Responsibility—namely, ensuring “that the client remains in control of the case.”

Some of its key takeaways are as follows:

- Any litigation funding arrangement should be in writing.

- The litigation funding arrangement should assure that the client remains in control of the case.

- The written document should address what happens to the funding arrangement if, down the road, the client and the funder disagree on litigation strategy or goals.

- Given that the propriety and the discoverability of litigation funding arrangements are unsettled questions in many jurisdictions (and may differ across contexts within those jurisdictions), (emphasis added).

Discoverability of ALF arrangements has presented a particular point of contention and uncertainty in that “[c]ourts currently are of differing views on whether the fact of third-party funding and the details need to be disclosed to the other side or are proper issues for discovery.” Thus, the report “identifies these issues but does not take a position on whether such disclosure should occur,” although it warns attorneys of the possibility and advises that they plan accordingly.

[1] ALF is also commonly referred to as “legal funding,” “third-party litigation finance,” and certain other terms. For relative simplicity and consistency with the Best Practices report, this article uses the ALF acronym.