This is a summary of the Hotshot course “Sandbagging,” an explanation of sandbagging in private M&A deals, including a discussion on pro- and anti-sandbagging provisions and how different courts and jurisdictions handle the issue. View the course here.

What Are Sandbagging Claims and Provisions?

- “Sandbagging” refers to when the buyer in a private M&A deal tries to enforce an indemnification claim that the seller breached a representation or warranty in the acquisition agreement, even though the buyer knew that the rep or warranty was false when it closed the deal.

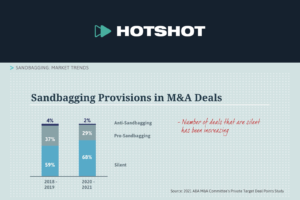

- Whether or not sandbagging claims are allowed is handled in one of two ways:

- The acquisition agreement addresses the issue by including a sandbagging provision in the indemnification section of the agreement; or

- The agreement is silent on the issue, in which case the governing law of the relevant jurisdiction will apply.

- There are two types of sandbagging provisions:

- Pro-sandbagging provisions.

- Also known as “savings clauses.”

- They allow the claims and are favored by buyers.

- Anti-sandbagging provisions.

- They prohibit the claims and are favored by sellers.

- Pro-sandbagging provisions.

- There are also pro-sandbagging jurisdictions and anti-sandbagging jurisdictions.

- Parties often include sandbagging provisions in their acquisition agreements to clarify whether these claims are allowed, particularly since jurisdictions differ on that question.

- Even in jurisdictions that are “pro-sandbagging,” there can be differences in the degree to which they allow sandbagging claims, so putting a provision in the agreement clarifies things.

The Courts and Sandbagging Claims

- Understanding why jurisdictions have different default rules on sandbagging involves a little history.

- Courts have followed one of two competing approaches:

- One based in tort law.

- The other based in contract law.

- These approaches relate to the historical treatment of representations and warranties.

- Historically, courts regarded warranties as promises that the buyer purchased as part of the purchase price, much like buying insurance.

- A wronged buyer needed only to show that the seller’s promise was breached and that the buyer suffered damages in order to recover under contract law.

- The buyer didn’t have to show any reliance on the warranties to recover.

- In contrast, courts historically considered representations as mere statements of fact made separate from the contract (even if they were contained in it) and made only to induce the other party to enter into the contract.

- A misrepresentation was not considered a breach of contract, but a wrongful act that caused harm to the other party.

- So the buyer’s remedy for a misrepresentation was based on tort law, and the buyer needed to prove that the untrue statement actually induced it to enter into the contract (that is, the buyer had to show reliance).

- If a buyer had knowledge of the misrepresentation prior to signing, it would be hard for the buyer to argue that it had relied on the representation when signing or closing the deal.

- Historically, courts regarded warranties as promises that the buyer purchased as part of the purchase price, much like buying insurance.

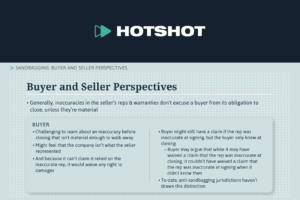

- U.S. case law no longer treats “representations” and “warranties” differently in the contractual setting.

- However, the distinction between the tort-based remedy and the contract-based remedy is still found in how different jurisdictions approach a buyer’s right to recover damages for breach of a rep or warranty.

- Jurisdictions that take the contract-based approach (where reliance isn’t necessary to recover damages) effectively permit sandbagging claims and are “pro-sandbagging jurisdictions.”

- This is the “modern” – and majority – “default” rule.

- Even among states adopting the modern approach, there are meaningful differences in how it’s applied, including:

- Different outcomes hinging on whether the buyer learned of the inaccuracy from the seller or independently; and

- Whether the outcome should differ depending on whether the buyer had knowledge at signing that the representation or warranty was false.

- The states that take a tort-based approach, requiring proof of “justifiable” or “reasonable” reliance before awarding damages, are the “anti-sandbagging jurisdictions.”

- Even if the buyer didn’t have actual knowledge of the inaccuracy, courts may inquire into the “reasonableness” of the effort made by the buyer to investigate the seller before signing – its “due diligence.”

- Courts may deny recovery in situations where even a modicum of effort would have uncovered the inaccuracy.

- If lawyers are comfortable with a state’s default rule, they may choose to have the contract governed by that state’s law.

- This means they achieve the desired “pro-” or “anti-sandbagging” result without needing to argue to include a sandbagging provision in the agreement.

- However, many lawyers either:

- Aren’t comfortable with the default rules of the states that would be logical choices for governing law; or

- Would prefer not to leave a determination up to the courts, which might interpret the default rule differently depending on specific circumstances.

- As a result, those lawyers include the contractual language explicitly permitting or disallowing sandbagging.

- The enforceability of these contractual provisions hasn’t been widely addressed by the courts.

- But the decisions that have addressed the issue have favored enforceability even when the provision was the opposite of the jurisdiction’s default rule.

This course also includes interviews with ABA M&A Committee members Nate Cartmell from Pillsbury LLP and Lisa Hedrick from Hirschler Fleischer LLP.