This is a summary of the Hotshot course “Indemnifiable Losses: Drafting,” a look at how loss is defined in acquisition agreements, including a discussion of buyer and seller perspectives and negotiating positions. View the course here.

Drafting the Definition of “Loss”

Buyer’s Draft

- This is a typical buyer-friendly definition of “loss” that would be included in a private acquisition agreement:

“Loss” means any cost, loss, liability, obligation, claim, cause of action, damage, deficiency, expense (including costs of investigation and defense and reasonable attorneys’ fees and expenses), fine, penalty, judgment, award, assessment, or diminution of value.

- It’s a comprehensive list of potential costs and expenses: “cost,” “loss,” “liability,” “obligation,” and so on.

- Some of the terms, like “claim,” “cause of action,” “fine,” “penalty,” “judgment,” “award,” and “assessment” are references to third-party claims by private parties or governmental authorities.

- Since it’s a buyer-friendly draft, it doesn’t limit these types of expenses to third-party claims only.

- It specifically includes “costs of investigation and defense and reasonable attorneys’ fees and expenses.”

- This is typically included in a buyer’s draft because the buyer wouldn’t be made whole unless the seller is required to pay these types of expenses.

- For example, if the buyer had to pay $100,000 in attorneys’ fees to defend a tax audit which resulted in the assessment of $10,000 in additional taxes, and the seller only paid the taxes based on the indemnification provisions of the acquisition agreement, then the buyer would suffer a $100,000 unindemnified loss.

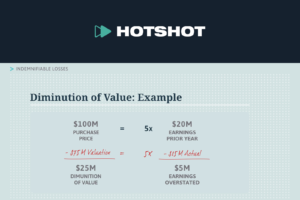

- Two other terms worth mentioning are “deficiency” and “diminution of value.”

- These terms have broad meanings which could be applied in a wide variety of situations where the buyer feels that the value of the target company or the assets is not what the buyer bargained for, and this deficiency or diminution of value can be tied to a breached rep or warranty.

- “Diminution of value” is seen as particularly beneficial to the buyer.

- It lets the buyer claim that any indemnified losses should be multiplied by the same multiple of earnings that was used in the calculation of the purchase price for the target company.

Seller’s Response

- A seller will usually respond to a draft like this by saying that the buyer’s definition is too broad.

- They’d delete “[costs of] investigation” to avoid having to pay for the buyer’s voluntary investigations to make a case against the seller.

- They’d often delete “claim” and “cause of action” because this language could be read to give the buyer the right to recover losses solely based on a third-party claim being made, regardless of the underlying merit of the claim.

- This issue is commonly referred to as the “claims if true” concept.

- A seller’s deletion of “cost of defense” and “reasonable attorneys’ fees and expenses” would usually be coupled with an agreement by the seller to pay those costs in connection with the defense of an indemnifiable third-party action against the buyer.

- This is usually dealt with in detail in the indemnification provisions of the acquisition agreement.

- A related issue is whether the buyer can recover the legal fees it incurred in enforcing its indemnification rights under the agreement.

- When a seller disputes an indemnification claim and the buyer incurs legal and other fees enforcing its right to indemnification, and the buyer is ultimately successful, the buyer should be entitled to recover the legal and other fees it incurred enforcing its indemnification right.

- While this concept is sometimes included in the definition of “loss”, it’s usually dealt with in the indemnification provisions.

- The seller will probably object to including “deficiency” and “diminution of value” in the definition to preclude a multiple-of-earnings theory.

- The seller may argue:

- That it has no control over or insight into how a buyer actually made its determination of the purchase price; and

- That any post-closing reduction in the target company’s value should be the buyer’s risk, because the buyer, not the seller, will receive the benefit of post-closing increases in the target company’s value.

- The seller may argue:

- The seller may try to reduce the indemnifiable loss by any tax benefit to the buyer.

- This argument is based on the fact that sometimes the buyer can deduct the costs that it seeks to be reimbursed by the seller in an indemnification claim.

- The seller argues that amounts to an unfair double recovery to the buyer in the amount of the tax benefit.

- Although this argument sounds reasonable, the amount and timing of any tax benefit is dependent on the buyer’s particular tax status and circumstances.

- This can lead to a very complex drafting exercise to document a tax benefit provision accurately.

- Because of this complexity, the offset for tax benefits is often left out of the definition.

- This argument is based on the fact that sometimes the buyer can deduct the costs that it seeks to be reimbursed by the seller in an indemnification claim.

- Similarly, the seller may argue that indemnifiable damages should be net of any insurance proceeds received by buyers.

- While not as complex to draft as the tax provision, buyers often object.

- Usually based on timing issues, since insurance payments are often delayed and subject to disputes with insurance carriers.

- They also object on the theory that premiums will be raised after receiving an insurance payment and the buyer will bear the cost of those increased premiums.

- If the indemnifiable loss does end up being calculated net of insurance proceeds, the acquisition agreement often also includes an affirmative obligation on the indemnified party to use commercially reasonable efforts to seek a recovery under any insurance policy covering the loss.

- While not as complex to draft as the tax provision, buyers often object.

- Sellers often add exceptions for consequential, incidental, and punitive damages.

- Their position is that compensatory or actual damages are sufficient, and other damages are too speculative and remote and could encourage conflict between the parties.

- Buyers will respond that excluding consequential damages could preclude the buyer from collecting damages that are the reasonably foreseeable result of a breach.

- An example of this is lost profits, which the seller tries to exclude by adding the consequential damages exception.

- Sometimes sellers and buyers negotiate this issue directly, and “lost profits” is either specifically included in or excluded from the definition of Loss.

- It’s worth noting that in deals in which the buyer’s right to recover on a post-closing indemnification claim is limited to representation and warranty insurance, there’s typically much less negotiation around these issues.

- This is because recoverable losses will be defined by the policy.

This course also includes interviews with ABA M&A Committee members Leigh Walton from Bass, Berry & Sims and Scott Whittaker from Stone Pigman Walther Wittmann.