This is a summary of the Hotshot course “Fraud Carve-Outs,” an introduction to fraud carve-outs and the issues parties consider when defining fraud, such as who’s liable, whose knowledge matters, what types of fraud claims can be brought, and what statements can form the basis for a fraud claim. View the course here.

Explaining Fraud Carve-Outs

- Indemnification rights for breaches of representations and warranties in a private acquisition agreement are typically heavily negotiated. The parties often agree to limit these rights through:

- Caps, baskets, and loss exclusions; and

- An Exclusive Remedy provision which says that the rights and remedies in the indemnification section are the only ones available if there’s a breach of the written reps and warranties.

- In addition, when a buyer gets rep & warranty insurance, a seller’s contractual liability for breaches can be eliminated altogether.

- There’s an important exception to these limitations for claims involving fraud that either the parties agree to or that’s imposed by law in many states:

- If the seller commits fraud when making reps or warranties to the buyer, the buyer wants to be able to bring a claim for that fraud, either as:

- A tort-based claim; or

- A contract-based claim that’s not subject to the caps and baskets that otherwise apply to indemnification claims—in this summary, this is referred to as an “uncapped indemnification claim.”

- If the seller commits fraud when making reps or warranties to the buyer, the buyer wants to be able to bring a claim for that fraud, either as:

- This exception for fraud is known as a “fraud carve-out,” and when the parties agree to it, it’s usually included in the Exclusive Remedy provision of the acquisition agreement.

- Whether or not to include a fraud carve-out isn’t typically an issue because sellers usually agree to include some form of it.

- The issue that does arise is whether and how the term “fraud” is defined for purposes of the carve-out.

- While fraud may seem straightforward, it’s actually a complex concept that parties need to define carefully.

- There are different types and sources of fraud claims as well as different states of mind that could be required to constitute fraud.

- Depending on how a fraud carve-out is drafted, there are also a number of remedies that could be available as well as various people who could be held responsible for that fraud.

- The parties need to weigh all these considerations and potential outcomes when negotiating a fraud carve-out.

- Sellers, of course, benefit from a narrow definition of fraud.

- They want to limit the scope of the fraud carve-out to a defined set of circumstances where the sellers deliberately included a representation in the agreement knowing it was false.

- Buyers prefer either no definition at all or a broader definition that includes misstatements made both in and outside of the agreement by any one of the sellers or their representatives.

- They want liability to extend to all sellers, including sellers who may not actually have direct knowledge of the underlying fraud.

- Sellers, of course, benefit from a narrow definition of fraud.

Leaving Fraud Undefined

- Many agreements leave fraud undefined, which can cause uncertainty and significant unintended consequences related to:

- The types of fraud claims that can be brought;

- The statements that can form the basis of those claims; and

- The people that could be held liable because of the fraud.

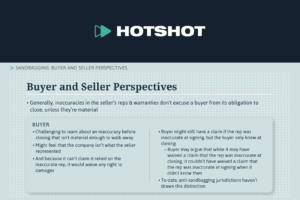

- In M&A agreements, reps are often seen as risk allocation devices—not literal statements of truth.

- A party may—and often does—make several reps believing them to be true, but without any way of determining (or any evidence supporting) their actual truth.

- If a fraud carve-out doesn’t clarify what counts as fraud, a party could be exposed to uncapped liability for:

- An innocent or negligent misrepresentation (known as “equitable fraud”); or

- A reckless misrepresentation (a type of traditional common-law fraud).

- For example:

- A seller may rep and believe that its business has been in compliance with all laws for the past five years, even though it doesn’t actually know for sure if the statement is true.

- Similarly, the seller may make a rep based upon information provided by its management team that a member of the management team knew to be false even though the seller itself did not.

- The seller agrees to make these reps because it’s a fair allocation of risk. And the seller is prepared to indemnify the buyer subject to the contractual caps, even though in both cases the seller has no actual knowledge of the truth or falsity of the reps.

- Even if it’s not the parties’ intention, an undefined fraud carve-out could expose the seller to the following possibilities:

- The seller could be responsible for recklessly making false reps even if the seller made those reps in a way consistent with industry practice.

- The seller could be responsible for innocent or negligent misrepresentations in the reps if the applicable jurisdiction allows these types of equitable fraud claims.

- The seller could be exposed to tort-based fraud claims or uncapped indemnification.

- Defining fraud helps protect against these situations and clarifies when the seller truly has uncapped liability.

Defining Fraud

- A well-defined fraud carve-out explains:

- The type of fraud that’s covered and the type of knowledge or scienter necessary to establish that fraud;

- Which statements can form the basis of fraud, meaning those made inside or outside the agreement;

- Whose knowledge matters;

- Who’s liable for the fraud; and

- Whether a party can bring a tort-based claim or an uncapped indemnification claim for the alleged fraud.

Type of Fraud

- There’s no unified definition of fraud across jurisdictions, so when an agreement leaves the term undefined it’s unclear which definition and therefore which type of claim and level of knowledge is intended. For example, there’s:

- Common-law fraud, which can be based on:

- A representation that was made even though it was known to be false;

- A representation that was made recklessly but without sufficient basis to actually know it was true; or

- Under certain circumstances, even nondisclosures.

- Equitable fraud, in which a completely innocent or at worst negligent misrepresentation made neither knowingly nor recklessly can constitute fraud; and

- Promissory fraud, which is a form of common law fraud involving the oral communication of a promise to do something in the future that the promisor allegedly never intended to actually do.

- This can effectively result in a breach of contract claim being recast as a tort-based fraud claim.

- Common-law fraud, which can be based on:

- Most buyers acknowledge that the fraud they have in mind when negotiating the carve-out is specifically when the seller knowingly makes a material false statement of fact that the buyer relies on.

- So buyers are often willing to include a definition of the term that matches this expectation.

- If the term is undefined, then the parties open up the possibility of any or all of the various types of fraud being included in the carve-out.

Type of Statements

- Parties also consider the type of statements that can form the basis of a potential fraud claim.

- A No-Reliance clause is when the buyer agrees that it’s not relying on any representations or duties to disclose other than those expressly set forth in the acquisition agreement.

- In most states, if the parties have included a No-Reliance clause in the agreement, only those written reps and warranties can form the basis for a fraud claim.

- When fraud is left undefined in the carve-out, there could be a conflict between the No-Reliance clause and the carve-out.

- This can raise questions about whether both contractual and extra- contractual representations should be allowed as the basis of a fraud claim.

Whose Knowledge Matters

- In addition, the definition of fraud can specify whose knowledge matters when it comes to fraud that’s based on a knowing misstatement.

- The definition could include a specific set of individuals (like certain named officers) or a larger group of people (like all sellers and the management team).

Who is Liable

- Similarly, parties sometimes specify who can be held liable for fraud.

- A poorly defined fraud carve-out can result in innocent sellers being liable for the fraud of the guilty sellers.

- If that’s the deal that the parties negotiated, then it’s not a problem.

- But if it was never discussed, then this could result in an unwelcome surprise to an innocent stockholder.

Type of Fraud Claim

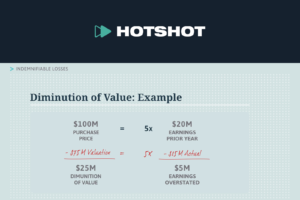

- Finally, whether a party can bring a tort-based claim or an uncapped indemnification claim for alleged fraud has implications on the party’s potential recovery and pool of defendants. For example:

- An uncapped indemnification claim based on alleged fraud might result in a larger recovery than a simple tort-based claim would in the applicable jurisdiction. The buyer may be able to seek damages from all of the sellers, regardless of whether they committed the alleged fraud.

- On the other hand, the definition of indemnifiable losses in the agreement might be so limited—for example, if punitive damages are excluded—that the buyer would be better off making a tort-based common law fraud claim even though that type of claim can usually only be brought against the culpable seller.

No-Reliance Clauses and Fraud Carve-Outs

- This summary doesn’t focus on No-Reliance clauses, but it’s important to understand how a fraud carve-out can undermine the efficacy of the provision.

- In most M&A agreements, buyers specifically acknowledge that they’re not relying on any statement made by the sellers or anyone acting on the sellers’ behalf other than the reps in the written acquisition agreement itself.

- The idea is that the parties have carefully negotiated the scope of what the seller agrees to stand behind, and they’ve put that in writing in the acquisition agreement.

- The seller doesn’t want to find out later that the buyer was instead relying on a statement made in a management presentation or a negotiation session even though those statements weren’t included in the written reps in the agreement.

- Since a required element of common-law fraud is justifiable reliance by the buyer, a No-Reliance clause can prevent any argument that the buyer relied on reps made outside of the contract.

- A fraud carve-out can undermine the efficacy of the No-Reliance clause. For example:

- Leaving fraud undefined could be interpreted to mean that both types of statements—those in and outside of the agreement—are included, despite a No-Reliance clause.

- Or if the parties include the fraud carve-out in the No-Reliance clause itself, it could be argued that they intend for both contractual and extra-contractual fraud to be an exception to no-reliance.

- If the express purpose of the No-Reliance clause is to eliminate all fraud claims that are based on extra-contractual statements by expressly disclaiming reliance upon any such statements, it doesn’t make sense to carve out fraud from the reach of the No-Reliance clause.

- So to avoid this pitfall and any other ambiguity, the parties usually define fraud so that it only includes knowingly false statements of fact set forth in the written reps of the agreement.

Judicially Created Fraud Carve-Outs and State Law

- Many states have laws that address the issue of fraud and No-Reliance clauses in acquisition agreements.

- For example, Delaware law, which is the governing law in most acquisition agreements, imposes a judicially created fraud carve-out in every acquisition agreement, regardless of any other contractually bargained-for carve-outs.

- So if an agreement governed by Delaware law has no fraud carve-out and a fully effective No-Reliance clause which eliminates all extra-contractual fraud claims, the Exclusive Remedy provision would eliminate all fraud claims based on the written reps.

- The exception would be when the seller itself knowingly makes a false statement in the agreement’s written representations.

- In other words, under Delaware law, even if the parties don’t include a fraud carve-out in the exclusive remedies provision, a buyer could still bring a tort- based claim if they believe the seller knowingly lied in the written reps.

- So if an agreement governed by Delaware law has no fraud carve-out and a fully effective No-Reliance clause which eliminates all extra-contractual fraud claims, the Exclusive Remedy provision would eliminate all fraud claims based on the written reps.

- When a fraud carve-out is included in an agreement governed by Delaware law, the seller will want to make sure to include well-defined limits.

- Otherwise the contractual fraud carve-out could increase the seller’s exposure well beyond the public-policy carve-out and potentially undo the carefully negotiated limitations on liability.

- Other jurisdictions have different views on these issues.

- In Massachusetts and some other jurisdictions, No-Reliance clauses are ineffective in the face of almost any type of fraud except claims based on negligence.

- Other jurisdictions have similar limitations on the effectiveness of No- Reliance and exclusive remedy provisions.

- Because state law can impose liability where the parties don’t intend there to be any, it’s important to familiarize yourself with the relevant laws of the governing jurisdiction before negotiating these issues.

The rest of the video includes interviews with ABA M&A Committee members Glenn West from Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP and Tali Sealman from White & Case LLP.