This is a summary of the Hotshot course “No-Shops,” a discussion on protective provisions in public M&A agreements, with a close look at the No-Shop provision and its main exceptions, Window-Shops and Go-Shops. View the course here.

Protecting Against the Interloper Risk

- When a buyer wants to acquire a public company target one of its main concerns is that between signing and closing, a competing bidder “jumps” the deal with a better offer, and the buyer loses the deal.

- This is the so-called interloper risk.

- Public company merger agreements protect against this risk through various deal-protection provisions. These provisions create a framework that covers:

- If, how, and when the target can engage with a competing bidder.

- This includes the no solicitation provision itself (often called the “No-Shop” clause), which restricts the target from soliciting competing bids and engaging with competing bidders.

- It also includes the exceptions to these restrictions—Window-Shops and Go-Shops.

- The target board’s recommendation to its shareholders and when it can change that recommendation.

- This includes the definitions of Superior Proposals and so-called Intervening Events.

- When the target or buyer can terminate the merger agreement and the related consequences.

- This includes matching rights, forcing the vote, and termination and termination fee provisions.

- If, how, and when the target can engage with a competing bidder.

- Deal-protection provisions can also apply to the buyer when buyer-shareholder approval is required (this is less common).

No-Shops, Window-Shops, and Go-Shops

- The No-Shop clause is the heart of the deal-protection framework.

- It prohibits the target from:

- Soliciting competing bids;

- Engaging in discussions or negotiations with a competing bidder; and

- Providing diligence access to a competing bidder.

- It prohibits the target from:

- These prohibitions apply to:

- The target;

- Its officers;

- Directors; and

- Advisors—like its investment bankers.

- No-Shops are not usually flat prohibitions.

- They often have one or two fiduciary-out exceptions:

- A Window-Shop; and

- Sometimes a Go-Shop.

Window-Shops

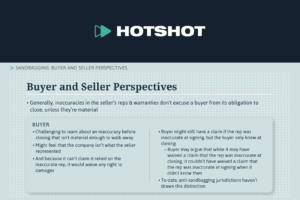

- Window-Shop exceptions let the target engage with a competing bidder that makes

an unsolicited proposal, but only if:- After good-faith consultation with its outside legal and financial advisors, the target board thinks that the bid could (or would) reasonably lead to a Superior Proposal.

- At this stage of the process, the target board doesn’t have to conclude that the new bid is a Superior Proposal—only that it could (or would) reasonably lead to one.

- After good-faith consultation with its outside legal and financial advisors, the target board thinks that the bid could (or would) reasonably lead to a Superior Proposal.

- Under a Window-Shop, the target can also grant diligence access.

- But it must enter into a confidentiality agreement with the competing bidder that meets certain parameters, like that:

- It’s generally at least as favorable to the target as the original buyer’s confidentiality agreement.

- But it must enter into a confidentiality agreement with the competing bidder that meets certain parameters, like that:

- If the deal has a two-step structure, the Window-Shop period lasts until:

- The tender offer expires; and

- The buyer accepts the tendered shares for payment.

- In a single-step merger, the Window-Shop period lasts until the target shareholder vote.

- This means that even if the deal remains pending for several months (e.g., because of a long regulatory delay), the target’s ability to engage with a competing bidder still ends at the time of the shareholder vote.

Go-Shops

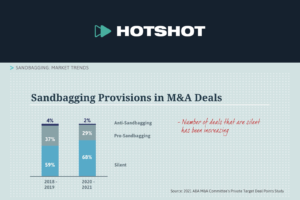

- In a minority of cases, the parties also include a Go-Shop provision.

- Go-Shops allow the target to actively solicit new bidders for an agreed period after signing.

- They’re mostly used in situations when a target board hasn’t run a pre-signing market check, such as a formal or informal auction.

- Usually, as long as the No-Shop includes common fiduciary outs, the target board can get comfortable that it’s securing an attractive deal, while preserving the ability to consider unsolicited topping bids.

- Sometimes, especially in private equity deals, the target goes one step further with a Go-Shop clause.

- A typical Go-Shop clause provides two benefits to the target:

- First, it gives the target a limited Go-Shop period (usually 30-60 days postsigning) to actively seek better deals instead of just being open to unsolicited ones.

- Second, if the target abandons the deal with the initial buyer and accepts a topping bid that originated during this Go-Shop period, then it doesn’t have to pay the full termination fee.

- Often, it only pays half the amount that would’ve been owed outside the Go-Shop period.

Notification Obligations

- Before a target can even consider terminating a deal for another bid, it has to first

notify the initial buyer—usually within 24–48 hours of receiving the proposal.- The target has to disclose the proposal’s material terms and conditions.

- This means that the initial buyer is kept appraised of the competing bid and the terms needed to match the overbidder.

- The target has to disclose the proposal’s material terms and conditions.

This course also includes interview footage with Jenny Hochenberg from Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer and Igor Kirman from Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz.