This is a summary of the Hotshot course “Sandbagging: Buyer and Seller Perspectives,” a discussion on buyer and seller perspectives regarding the issue of sandbagging featuring insights from ABA M&A Committee members. View the course here.

Buyer and Seller Perspectives

- In this section we’ll look at the buyer’s motivation to include a pro-sandbagging provision in an acquisition agreement and the seller’s point of view.

- Under most acquisition agreements, inaccuracies in the seller’s reps and warranties don’t excuse the buyer from its obligation to close, unless the inaccuracies rise to a certain level of materiality.

- For the buyers, that becomes challenging if:

- The buyer learns about an inaccuracy in the reps before closing; and

- The inaccuracy isn’t so material that it gives the buyer the right to walk away.

- The buyer might feel that the company it’s about to acquire isn’t what the seller had represented.

- And, because it couldn’t claim that it had “relied” on the inaccurate representation in proceeding to close, it would have waived any right to damages.

- Note — a buyer might have a claim if the rep was inaccurate at signing as well as at closing, but the buyer only had knowledge of the inaccuracy at closing.

- The buyer could argue that while it may be deemed to have waived the inaccuracy in the rep made at closing because it was aware of the inaccuracy and closed over it, it could not have waived the inaccuracy of the rep made at signing if it was unaware of the breach at the time.

- However, to date, anti-sandbagging jurisdictions appear not to have drawn such a distinction.

- By proceeding to close with knowledge of the breach, a buyer waives both claims.

- Note — a buyer might have a claim if the rep was inaccurate at signing as well as at closing, but the buyer only had knowledge of the inaccuracy at closing.

- Sellers stress the injustice of:

- A buyer learning of inaccuracies in the seller’s proposed reps before the acquisition agreement is signed or between signing and closing; and

- “Lying in wait” to recover damages post-closing.

- Rather than bringing the inaccuracies to the seller’s attention and perhaps renegotiating the purchase price.

- There is another reason buyers want pro-sandbagging provisions in their agreements.

- Let’s say that after closing:

- A buyer discovers an inaccuracy in a rep and tries to recover under the indemnification provision for the breach.

- The seller acknowledges that there was a breach.

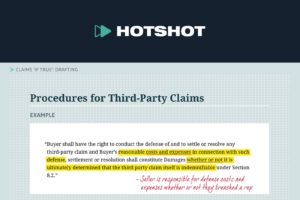

- Without a pro-sandbagging provision, the seller can challenge the claim by alleging that the buyer did in fact have knowledge of the breach as a result of the buyer’s due diligence review.

- The buyer would then be subject to the cost and delay of an evidentiary hearing before being able to recover, and the result of that hearing would be uncertain.

- The pro-sandbagging provision takes the knowledge issue off the table, both in terms of:

- Making a claim; and

- Getting paid quickly.

- Let’s say that after closing:

- For the large (and growing) number of transactions in which the buyer obtains rep & warranty insurance, the debate over sandbagging is usually moot.

- This is because under the terms of the insurance, the buyer is required to deliver a “no claims” certificate and can’t make a claim for breaches that:

- It was aware of pre-signing; or

- Came up between signing and closing.

- A buyer may still seek inclusion of pro-sandbagging language when the seller is “backstopping” the insurance.

- This means that the seller is responsible for claims not covered by the insurance.

- A seller backstopping the insurance may seek a representation in the acquisition agreement saying that the buyer knows of no breaches other than those disclosed to the insurer in the no-claims certificate.

- This is because under the terms of the insurance, the buyer is required to deliver a “no claims” certificate and can’t make a claim for breaches that:

- Sandbagging provisions only address a buyer’s ability to seek damages in contract for inaccuracies in the reps and warranties in the agreement.

- Pro-sandbagging provisions do not eliminate reliance as a required element for a tort claim:

- Brought by the buyer under the so-called “fraud exception” found in the exclusive remedy provisions of most acquisition agreements; or

- Brought for misrepresentations or omissions made by a seller to a buyer beyond those contained in the agreement itself (e.g., during buyer’s due diligence)

- Pro-sandbagging provisions do not eliminate reliance as a required element for a tort claim:

This course also includes interviews with ABA M&A Committee members Nate Cartmell from Pillsbury LLP and Lisa Hedrick from Hirschler Fleischer LLP.